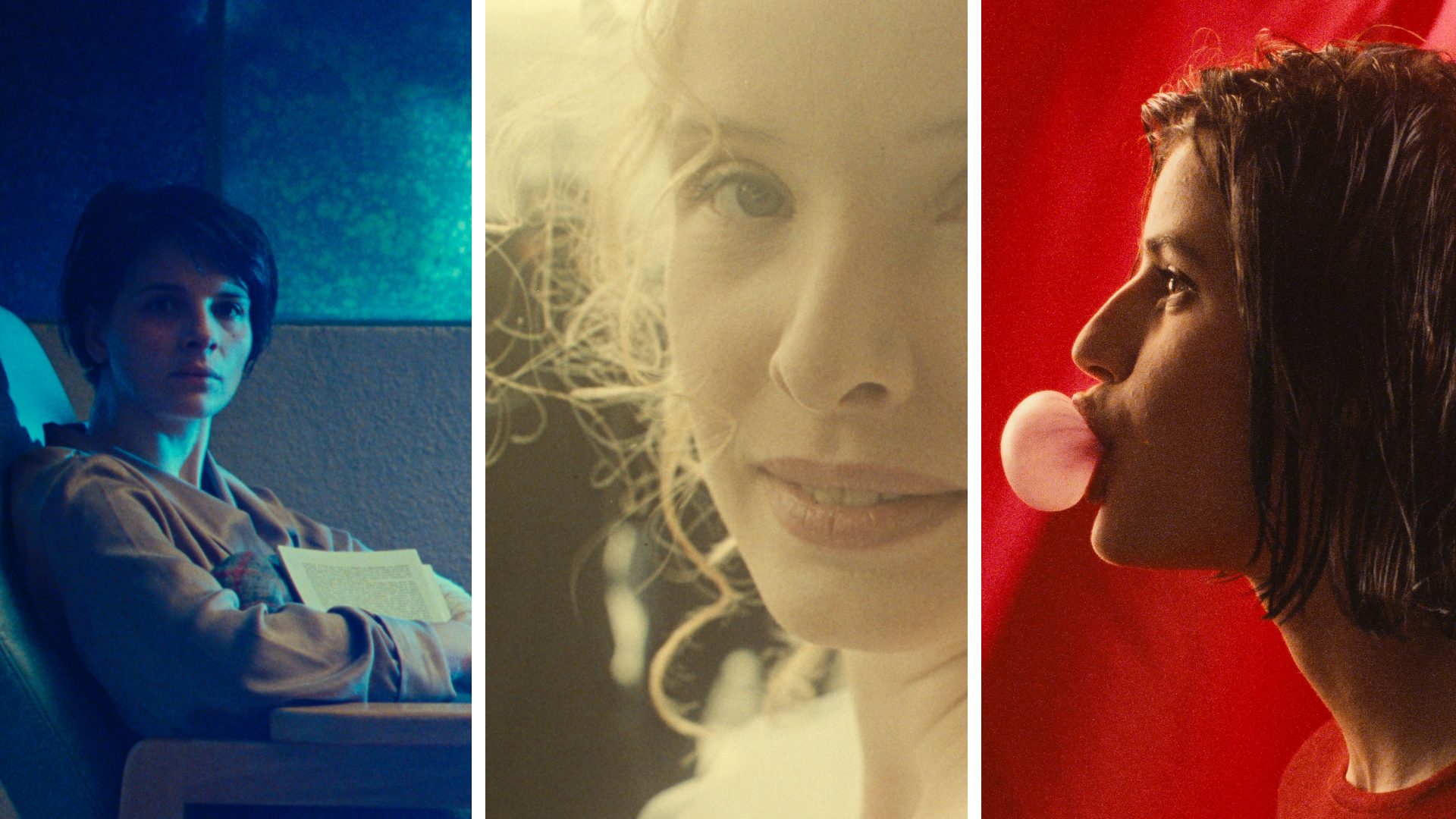

It’s almost eerie to see The Three Colours Trilogy: Red, White and Blue back on our screens and looking as fresh as it did when the films came to define the essence of the European cinema of the 1990s. Although each of the three certainly pings off the screen with a renewed clarity and brilliance, their impact isn’t simply due to the sparkling new 4K restoration of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s masterworks.

According to one of the trilogy’s luminous stars, Irène Jacob, who played Valentine in Red, the key to these films’ enduring status is creativity – and love. “When you allow a filmmaker to express himself with complete freedom in all aspects, you unleash a kind of creativity that will always be alive,” she tells me. “It is such a strong energy, a creativity like this, that it endures for ever, as long as we look after it.”

Jacob is talking to me from her Paris apartment, and even over a mid-morning Zoom she looks as radiant as she did for the Polish director in those towering works of the 90s, The Double Life of Véronique (1991) and Three Colours: Red (1993). How does it feel to see herself restored on screen?

“I can’t watch it,” she confesses. “It’s too much, too emotionally difficult. It’s as if it’s not me, like it’s somebody else and I don’t even find talking about it very easy. It is part of my body and my soul, but it’s also something in the past and it reminds me of the people who aren’t with us any more, like Kieslowski and like Trintignant. So I find it a bit mournful, a bit forbidden.”

Cinema can do that. It’s like watching ghosts. Seeing these three films again, I was transported back to my own younger self, to when and where I first watched them: Blue, in Paris at the UGC Bastille; White, falling in love with Julie Delpy, at the Beaubourg (now MK2 Beaubourg, a chain named for its founder, Marin Karmitz, who made his reputation and some of his fortune as producer of this trilogy); Red, in London, at the Curzon Mayfair.

So deeply did I fall for these movies that I felt those moments flood back, and remembered thinking how I’d like to meet all those actresses. I’ve interviewed Binoche and Delpy before (she even wrote the intro to the French translation of my Woody Allen book) and today marks some kind of personal hat-trick, meeting Jacob, even if it has to be electronically.

I wonder if she met Binoche and Delpy while they were making these three landmark movies? “Not really,” she says. “Kieslowski made them back to back, in order, and he was editing Blue and White while we were making Red, but the casts only ever came together for one day, which is shown right at the end of Red, but which we shot before we’d even made Red, and even then we are not on the screen at the same time. You see, it sounds very complicated, but it was all very calm.

“So even though I knew about the other films – I had read the scripts of Blue and White, I don’t know if the other girls did – it wasn’t part of my main work. Of course, now we are bound together by the film, and when we meet, it is strange because people like to put us together as one. But we really weren’t. But we are part of a family now, because whenever I see them, Julie and Juliette, I think of them as my cousins.”

She’s right. The three female stars became emblematic, symbols of European intelligence and emotion. It’s hard to overstate the impact of the trilogy. You could tot up the awards – a Golden Lion at Venice for Blue, a Best Directing Golden Bear at Berlin for White, and three Oscar nominations for Red at the 1995 Oscars following a campaign that was led by Martin Scorsese and Sean Penn, among others, after it was rejected by finicky Academy rules as the official Swiss entry for not being Swiss enough. But these awards don’t number half as many between them as those won by Everything Everywhere All At Once, for example (and I can’t see I’ll be writing about that film in 30 years).

I mention to several friends over the weekend that I’m writing about Three Colours. All of them give a little sigh, all of them triggered into a reverie and an anecdote about where they saw them, with whom, how they felt, how they bought the soundtrack albums by the composer Zbigniew Preisner (the second best-ever Zbigniew, after former Juventus striker Boniek). When I tell them it’s 30 years ago, there’s another shudder of shock. But their love for these films and the experience of watching them clearly affects them all, still.

The overall theme was to make three films discussing the three tenets of the tricolour flag, the Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité of the French Revolution. But the films, I think, are also about borders – in Blue, there’s a piece composed in the movie called Song for the Unification of Europe. I remember feeling very moved by that 30 years ago, and how it felt possible and bright, coming from a director who just a few years previously was behind an iron curtain. So these films, made in Paris and Geneva, dealt with grief and rebirth and generational conflict created by an artist fully prepared to explore keenly-felt themes just as borders and walls were coming down in Europe.

In Blue, Binoche is a woman grieving after a car crash has left her composer husband and daughter dead. Trying but failing to end her own life, she attempts to cut all ties to her past – a sort of freedom – but finds fragments of it keep pulling her back. In White, a more comic scenario finds Karol, a Polish immigrant to Paris (Zbigniew Zamachowski, another fine Zbigniew) dumped by his wife (Delpy). He ends up destitute and begging on the streets until he tries to restore some kind of equality in his life by getting back to Poland, becoming rich and enacting twisted revenge on his ex. In Red, the theme of fraternity is explored in the loose but powerful connection between Jacob’s Valentine and Jean-Louis Trintignant’s retired judge, as well as several other characters who live near both of them.

“It’s a very creative form of cinema,” Jacob reiterates. “And that’s why it still feels so modern. When something is inventive and has a freshness of vision, it will last, and this school of cinema, out of Łódź in Poland, was all about trying to tell something in a way that’s never been told before, and Krzysztof challenged himself: how can we talk about freedom, equality and brotherhood in a way that’s not been seen?”

Jacob has a flourishing acting career. You can see her in current Euro-series Liaison, with Vincent Cassel and Eva Green on Apple TV, and she’s on the Paris stage at the moment in a play called House, by the Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitaï – although they cancelled the show the night before I spoke to her, in solidarity with the strikes and protests sweeping France. She’s despondent, like most of us, that European borders and communication and connection, all major themes of the trilogy, are now seemingly diminished, that dialogue is so entrenched and at an impasse.

So it lends even more significance to the role she takes most seriously now, as president of the Lumière Institute in Lyon, when she was elected in October 2021 to succeed the late Bertrand Tavernier in the post. “Our job now is to preserve cinema like great works of art and these films are most definitely that,” she says. “We don’t forget about Michelangelo or Picasso, no, they talk to us today. If you see a fantastic Renaissance painting in a museum, or a Rembrandt, and you know that feeling you get when you stand in front of it and it looks like it has just been made? That’s what you get with the best cinema, when an artist is allowed the freedom to explore and create in his own way. So it is a duty and an honour to talk about the films, to keep them alive.”

Jacob has been carrying the torch for these particular films for three decades. She says she gets letters and emails about them every day. Her enthusiasm remains undimmed. Partly, she says, because the films clearly mean so much to the people who have seen them. She has travelled to Japan, Brazil, India and been amazed by audiences who have such clear affection for and connection to the material.

“I think they’re so personal because Krzysztof never explained them,” she says. “If ever a scene was getting too explicit in meaning, that’s when he would shout ‘Cut’. So his style forces the audience to fill in the gaps themselves using their own emotions and experience – it’s open for you to be involved and engaged in it, and that’s how the material manages to have such a long life: it is always alive to interpretation.”

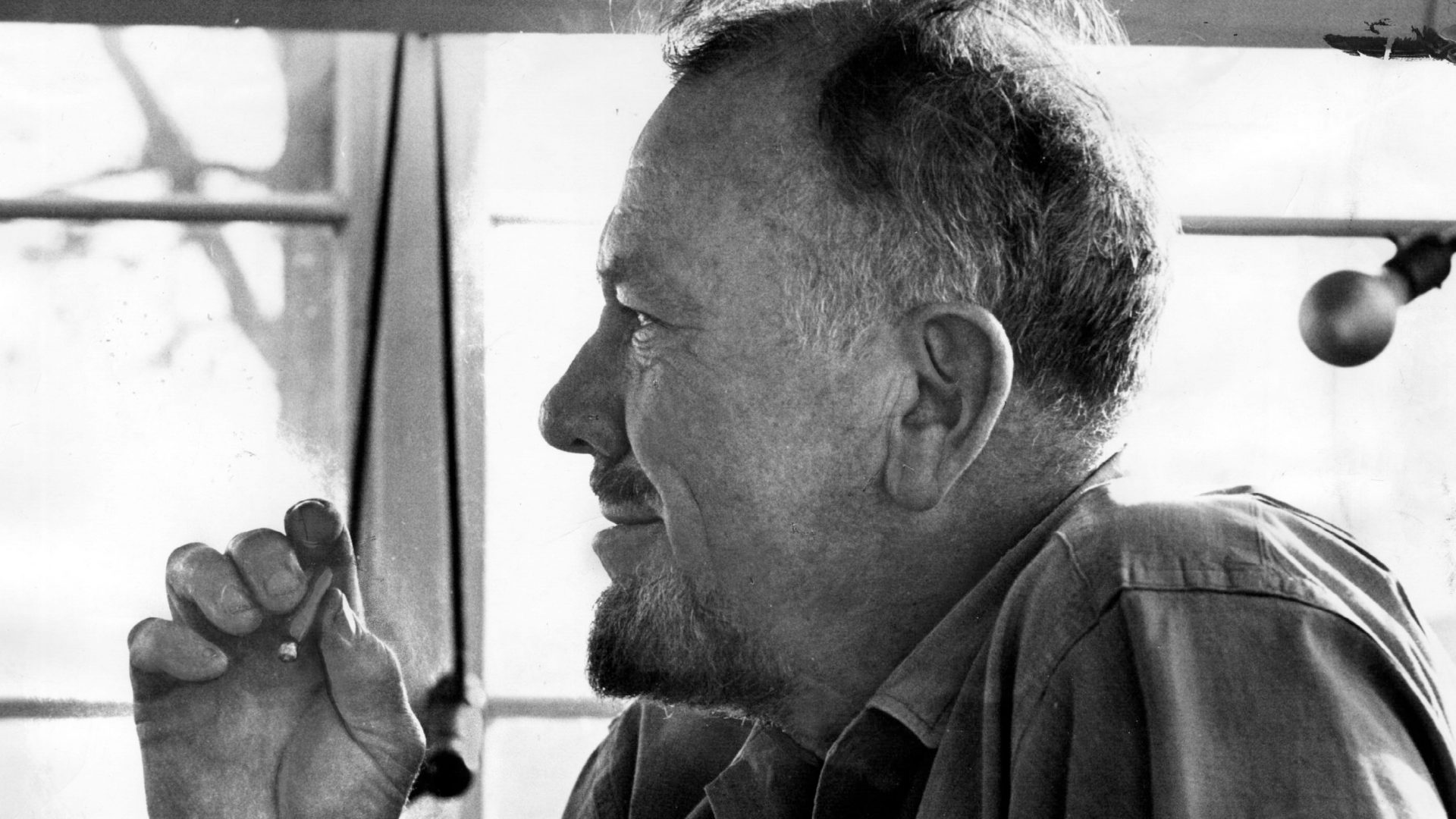

We talk about filming Red and her mysterious relationship on screen with the legendary Jean-Louis Trintignant, who plays the compromised judge Kern in the film, caught snooping on his neighbours’ conversation through phone-tapping.

“He was an amazing performer,” she sighs. “But difficult. He would say ‘No’ with a smile, always doing something unexpected, lots of layers, with this very questioning delivery, he would say one thing but that could mean the opposite, always a mystery in his eyes. We would rehearse our scenes together, more to know where to sit and where to stand, and Krzysztof was right in the middle of us, with his coffee and his cigarette, like he was in the frame and acting in the scene and he was like watching tennis, you know, back and forth, and Jean-Louis found this quite annoying, but he remained calm even when he asked Krzysztof to get out of the way.”

I ask whether Kieslowski encountered the same problems with Trintignant that every director did, namely that the actor was always announcing his retirement and would prefer to stay in his garden in the south of France. “Yes, of course,” Jacob says with a laugh. “Jean-Louis kept suggesting other actors, said he was retired, that the role wasn’t for him, but then his daughter Marie showed him Krzysztof’s films and told him what a great filmmaker he was, so they met in the garden and became good collaborators. Jean-Louis was also recovering from a car accident, and Krzysztof told him he could use his real walking stick in the movie, which he did and it was perfect for that character. He also uses it in the movie he did afterwards, the directing debut of Jacques Audiard, Regarde Les Hommes Tomber (See How They Fall), I loved him in that film so much.”

There is almost too much to talk about. We barely touch on La Double Vie de Véronique, the film she made with Kieslowski before the Three Colours, in which she plays two parts, in Polish and in French. The role earned her Best Actress at Cannes in 1991 and remains a haunting masterpiece, while the music, again by Preisner, has become a classic soundtrack.

We talk, briefly, about her first role, as a piano teacher, in another of my favourite films, Au Revoir Les Enfants, by Louis Malle in 1987, and about her Desdemona opposite Laurence Fishburne in Oliver Parker’s under-rated 1995 Othello adaptation, with Kenneth Branagh as Iago.

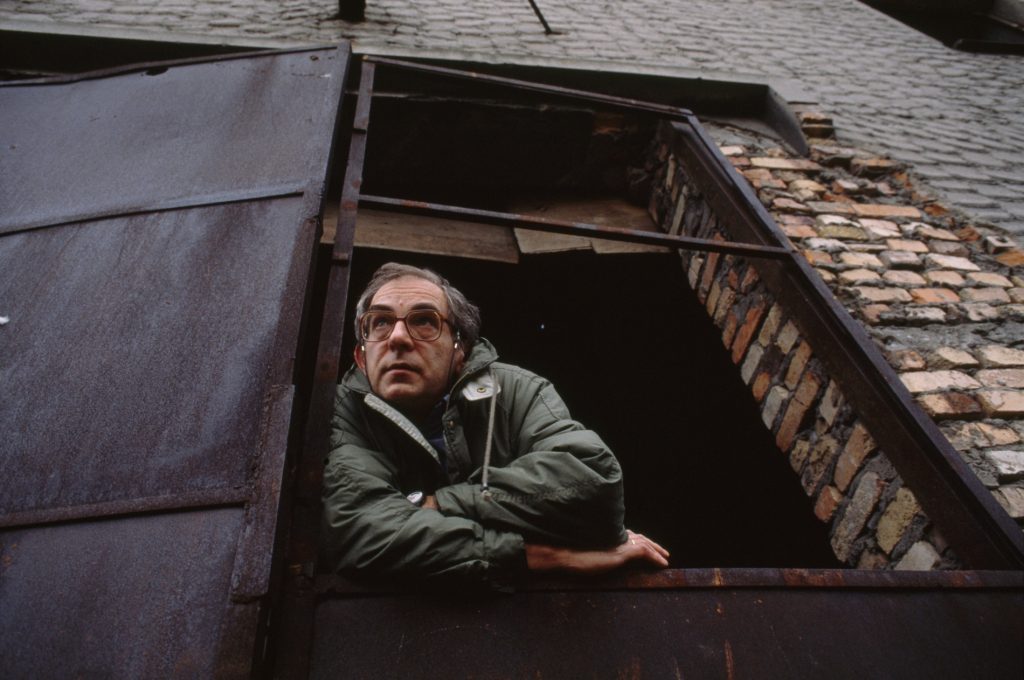

I talk to Parker – whose directing career went on to include comedies An Ideal Husband, St Trinian’s and Dad’s Army as well as the recent hit TV show Funny Woman – about working with Jacob and the impact of seeing her in the trilogy.

“It was mesmerising, frankly,” he says. “Kieslowksi was an astonishing director and she was clearly mesmerised by him and working with him. I thought it might be a tough act to follow as a director but she just had this glow. There’s no veil in her relationship with the camera. She reminded me of Ingrid Bergman, not so much physically, but in the soulful power she radiates and the integrity and honesty about her reactions.”

Parker had seen The Double Life of Veronique and Three Colours: Red and wanted Irène for Desdemona to bring an internationality to his cast, so that it would underline the difficulty of communication between her and Fishburne’s Othello (the first time a black star had played the Moor on film.)

“I think she came from Kieslowski with an ability to be absolutely in the moment, to surrender to what’s coming to her and convey a depth of listening. I didn’t need her to be perfect at pentameter but I wanted her to get into the soul of the thing, and she really did that. She can’t bullshit, so fierce is the honesty with which she infuses the screen.”

Parker says he’s waiting to pass on Three Colours to his own son. He recently made a list of 20 films he feels are essential viewing and the trilogy was firmly inscribed on it, before he even knew of the new restorations coming out. “Kieslowski had such a tough edge in his films, like in the Dekalog, which burned with a clarity into your eyes,” he recalls.

“So when he went to France and worked with that tradition of sophistication and emotion, and with an actress such as Irène, it had a searingly powerful effect. They held everyone who saw them at the time in a sort of spell.”

Jacob agrees that the Kieslowski films are somehow special, much as she loved her other films. “You see, these are great films, too,” she says, “but you never know how rare it will be to be in something like Three Colours that everyone falls in love with. Only years later can you tell how precious that experience is. You have to put all your effort into keeping it alive. This is our job.”

She’s a passionate advocate for the cinemathèque work she is tasked with in Lyon, where she works closely with Cannes boss Thierry Frémaux, who also runs Lyon and its October festival of retrospectives and restorations.

“I am a surviving human link to a film of great creativity,” she says. “Out of that comes dialogue that extends that passion into the future, so films like Three Colours can inspire new generations. This is my job now and I don’t take this duty lightly, because to do it is to stand up for free expression in cinema, and that’s where you get the artists of the past still talking so vividly to us today. And that is how cinema will survive, through love: les amoureux de cinéma, like you and me.”

All films are released in UK cinemas in their 4K Restoration. Three Colours: Blue from Friday 31 March, Three Colours: White from April 7 and Three Colours: Red from April 14

Three Colours Trilogy | 7-disc 4K Ultra HD & Blu-Ray set is released through Curzon on April 17