It is the worst helicopter crash in Royal Air Force history, one that killed several high-ranking members of the security establishment who were conducting Britain’s conflict in Northern Ireland.

But the story of the Mull of Kintyre Chinook accident on June 2, 1994 remains untold.

What is now known, 30 years on from the crash, is that a veil was thrown over the tragedy from the beginning.

The case joins a long list of other national scandals, each one of which saps the integrity of government and merely adds to the distrust now on trial during this election cycle.

From Hillsborough to the Tainted Blood Inquiry to the Post Office injustices, the divine myopia of unelected, unnamed yet permanent script writers inside the civil service has created in England, and on an industrial scale, a machinery of cover-ups that relies on the hope that snail-paced progress will outlast the cheated and bereaved.

On June 2, the families and colleagues of the 28 men and one woman who died in disputed circumstances on the Mull will remember them, 30 years on. The Ministry of Defence will not, choosing to offer no formal ceremony.

Recent headlines from the brother of the helicopter co-pilot and a widow of an RUC officer who died that day make the point that this insulting omission is simply another emblem of officialdom’s desire to suppress: to suppress feelings, to suppress memories, to suppress the facts.

I stood above the crash site as a junior reporter for the Belfast Telegraph the morning after the crash in 1994, bewildered by what had just happened.

It was the single biggest loss of life for the British security forces during the entire conflict in Northern Ireland. Two months after the crash came the beginnings of the peace process, with the first IRA ceasefire of the 1990s taking place on August 31, 1994.

The casualties were a who’s who of the security establishment. There were 10 RUC Special Branch officers, nine soldiers mainly with military intelligence, five members of MI5 and one civil servant.

These men were involved in some of the biggest episodes of the Northern Ireland conflict, including the incident in Gibraltar where the SAS killed three IRA members, and Loughgall, where the SAS killed eight members of an IRA squad attacking a police station. The sole woman on board was Anne James, of MI5.

The head of Special Branch, Brian Fitzsimons, who was soon to retire, was among the dead. John Deverell, the deputy head of MI5 and the lead spy in Northern Ireland whose team was involved at that time in secret discussions with the IRA, also died. The soldiers included Col Chris Biles, who was expected to climb the ranks to the top of UK command as a full general.

Chaos in the hours after the crash was exemplified by the staccato requests from government asking the media to not name the five from MI5. Hours after that, the government conceded this was impossible.

In the weeks and months that followed, in a pattern that so often played out for so many other families, it was the unending sense of disbelief, pain, anger and helplessness that an accident of this magnitude had happened. It was a paralysing loss for all concerned.

The helicopter that crashed had no data or cockpit voice recorder. This was despite money having been earmarked for its installation years earlier. The absence of voice and data information permanently removed the pilots’ right of reply at the investigation stage.

There were no survivors. The wreckage was a mess, and although the “personality” of the crash, to use the language of air investigators, suggests it was not the result of a missile strike or bomb on board, the violence of impact meant there was little evidence relating to the condition of the aircraft in the minutes before the crash.

There were “earwitnesses”, who felt the downthrust of the rotors as the helicopter crashed above them, narrowly missing them. The fog on land was so dense the lighthouse keepers didn’t see the helicopter approaching or crashing.

The closest there was to an eyewitness was out at sea, where a yachtsman who was trained as a scientific instrument maker watched the helicopter fly by, at moderate height, in level flight, not at excessive speed.

The yachtsman, Mark Holbrook, gave evidence to a number of inquiries that he could see the Mull of Kintyre quite clearly, and there was fog higher up the cliff face. The pilots would have had the same view.

The final radar trace around the time of the crash shows a disputed and still unexplained symbol moving near to the aircraft at the time of the accident. A flock of birds? Something else?

A final radio call made by Fl Lt Jonathan Tapper, the captain of the flight, routine in nature and made a few minutes before the crash, went unanswered despite being received and recorded by air traffic control. It was the perfect mix for conspiracy theorists, and it didn’t take long for them to rise to the surface.

For the first time, the board of inquiry set up to investigate the incident was subject to outside consideration, because John Major, as prime minister, thought it should be publicly scrutinised under his open government plans. Transparency, he felt, would improve accountability and decision-making.

The problem was that the Ministry of Defence and the Royal Air Force had for years made decisions about accidents in secret, and the new policy of openness led to conclusions that were inconsistent and muddled. The RAF’s standards were called into question when it emerged the president of the board had cleared the pilots of blame, but that two more senior officers had overruled that finding.

These senior officers apparently decided that, although they had no proof, they did enjoy “the burden of rank” and in their opinion the answer was clear – the pilots did it. And so that was the finding that was released publicly a year or so after the crash – that is where the story was supposed to end.

When the television drama outlining the Post Office scandal set the country alight with a raw sense of injustice, there was a brief focus on a former MP who had done the right thing by four of his constituents, who were also sub-postmasters. They told him they were worried about the software they were being asked to use.

James Arbuthnot, the then MP for Hampshire North East, listened to the sub-postmasters’ concerns and turned history ultimately in their favour. His belief in asking the tough questions on behalf of honourable constituents accused of terrible things by a faceless bureaucracy is rooted in the Chinook crash, and it is an inspirational link.

Arbuthnot, a former head boy at Eton, a Conservative MP in a safe Tory constituency – an establishment man – had no reason to answer my calls and letters when I contacted him out of the blue three years after the Chinook crash. But the Special Forces Chinook squadron was based in his constituency, at RAF Odiham, and the co-pilot who died, Fl Lt Rick Cook, was a constituent.

The SAS had created a new role for a dedicated helicopter pilot and Cook had been due to take up that position in September 1994. Cook was a classic special forces aviator, highly skilled and willing to take risks. He flew at night using night vision goggles and even once flew into a tunnel in a valley in Wales on a special forces training exercise with barely room for the rotors to fit.

He learned how to fly low over lakes and over the sea, where the salt water can wreck the gears. Pilots don’t like water, which is why they choose the air force, not the navy. But special forces pilots are trained to drop soldiers on to ships, and even to launch boats, hovering almost at sea level with the tailgate of the Chinook dipping into the water. The boat then slides out of the back.

Also aboard that day was Master Air Loadmaster Graham Forbes, who served on the recovery in the aftermath of Lockerbie and who was among the most experienced crewmen. He was at the front of the helicopter in constant communication with the pilots. If he felt conditions were unsafe he would have ordered an abort or a hover. Under Special Forces rules, the handling pilot, Fl Lt Cook, would have instantly complied.

Sgt Kev Hardie, at the back of the aircraft, had similar responsibilities. He had been part of the crew who had flown Bravo Two Zero, an eight-man SAS patrol into Iraq during the Gulf war of January 1991.

The captain of the flight, Jon Tapper, was the special forces electronic warfare officer. He had grown so concerned about the Mark Two aircraft that he phoned his superiors in England asking to have a more reliable, older Mark One model made available. His request was denied. Fl Lt Tapper had flown the straight route from Northern Ireland to Mull weeks earlier when he had taken engineers to the lighthouse for repair work. So four sets of well trained eyes and ears were on the mission. What could have gone wrong?

Arbuthnot and I didn’t know one another, or anyone in common, but I expressed a concern based on research that the Chinook crash verdict was too neat, too tidy, unjust.

Andy Fairfield, a former Chinook pilot and friend of Rick Cook, joined me in meeting Arbuthnot at Westminster at the end of 1997, some 15 years before he would be engaged again, this time to right the Post Office injustice. I gave him two papers.

One was a list showing the technical problems with the crash aircraft in the weeks before the accident, specifically from April 8, 1994 to June 2.

A second document described the problem with the computer software on the aircraft. While the Chinook fleet had been flown for decades, the crashed aircraft belonged to a new generation of helicopter that in the mid-1990s was using technology that wasn’t well understood. It turned out that, unknown to us all at that time, the MoD was suing the engine manufacturers over the engine control system. This was never mentioned to any inquiry.

Arbuthnot took the lessons from Chinook when he raised the issue of the Horizon software used by the Post Office.

The two sagas were characterised by intransigence in the face of the evidence. Go slow, then slower. Play the roles of judge, jury and executioner. Do not allow independent scrutiny, patronisingly reassure the questioners you have all the answers and that there is no evidence to the contrary. Apply the brakes. Above all, hold the line.

It took 17 years for the pilots to have their honour restored, with an apology from the floor of the House of Commons. That was important to the pilots’ families. It was only a matter of honour – there was no financial benefit asked for, or received. Honour restored. It has a nice ring to it, but it took too long.

Post Office, Hillsborough, Tainted Blood – all of these took as long, or longer. The cynical belief was that time would kill off the passion and the curiosity. But those holding the line seem to not understand that justice has no expiry date.

Since 2011, families of the passengers have approached me to ask for information that for two decades they had never thought existed or they were too overwhelmed by bereavement to ask for. Ironically, as this 30th anniversary approaches, it is the children of the lost, in addition to the widows still alive, who are asking for more answers to their questions. It follows a two-hour documentary for the BBC that aired in January.

At the top of the list of questions is why the Chinook documents that have never been made public are formally under lock and key for 100 years, until 2094. Whatever the motivation for this, the effect is the children of the lost will be dead too if this unfeeling delay continues unchallenged.

Labour and Tory governments have responded slowly when they had a chance to do more. The idea that this is an accident from long ago does not make the transparency demands any less relevant.

Indeed, European law remains relevant to the case, specifically article two of the Human Rights Act, which enshrines the right to life. If loved ones have died in circumstances that involved the state, those bereaved have the right to a full and proper investigation. It shouldn’t take law to force the hand, but the law is there to be used.

And so there only remains one question – what really happened? We cannot give a definitive answer, and yet we do know certain things. We know for example that the flight was going low, and there are two reasons for this.

First, the aircraft flown was an experimental model and couldn’t fly in temperatures below 4C, due to the possibility of icing. That temperature limit was forecast to be met over Scotland and so high-altitude flight was ruled out.

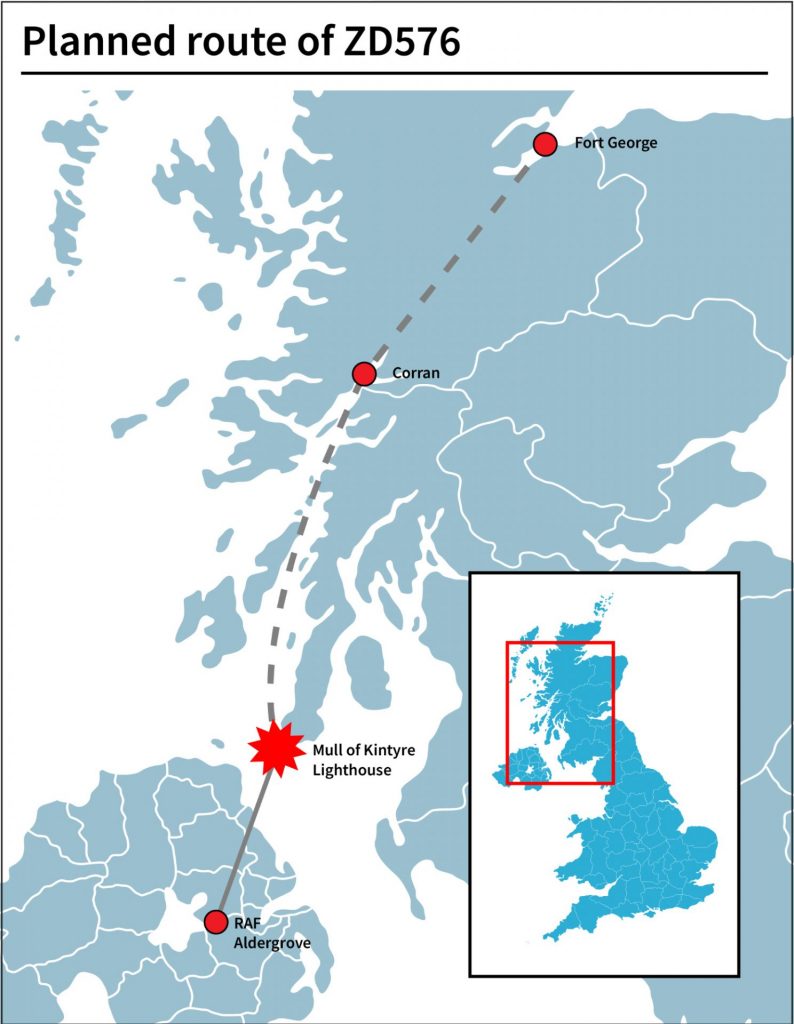

Second, the crew map shows the route, one that was approved by superiors before takeoff. The first focus was the Mull of Kintyre headland. Once visible there was to be a left turn and a low flight up to Corran and then on to Inverness, popping up at Fort George. Yet the aircraft hit the first piece of land it could. We know the land was visible from the cockpit. Why did it not turn?

One possible explanation is that the Chinook had had repeated incidents where the wiring for the controls had become detached, meaning that a crew member had to check the wiring every few minutes to make sure it hadn’t come loose. Any “debonding incident” would make the aircraft instantly uncontrollable. One investigator who looked at this design said: “I wouldn’t have this on my bike.”

There had been other malfunctions. Pilots had reported that when they flew for a period in straight flight and then inserted a move left, the aircraft could instead begin to turn right.

Also, the engine controls on the Chinook, airframe ZD576, had a series of software code problems classified as E5 errors. A single E5 error was considered potentially catastrophic because it could lead to the rotors speeding up uncontrollably.

Into this helicopter were placed 25 passengers and a four-man crew. The two pilots were flying the aircraft against their better judgment – and it is probably also fair to say, against their will.

Neither pilot was supposed to take this mission but they chose to, in part because it got them out of Northern Ireland for a bit and they could even stay in Scotland for the night if it was getting late, and second because the other Chinook pilots in Northern Ireland were less qualified.

The RAF’s best of the best took off at 5.42pm. The last words they heard came over the radio from a woman working at the air traffic perimeter at Aldergrove: “Bye bye.” Within 20 minutes, all were dead.

David Walmsley has spent 30 years investigating the accident. He is editor-in-chief of Canada’s Globe and Mail