There’s nothing to see here. That’s the feeling you get if you stand in front of the fresh fruit and veg shelves in many British supermarkets at the moment – and also the message you get from Tory MPs and parts of the retail industry when you ask if Brexit might be partly to blame.

There’s no doubt that bad weather in the Med is the root cause of these shortages. But what they won’t tell you is that underlying problems caused by Brexit are also paying a part. And they also won’t tell you that things could soon get much, much worse.

For the truth about the current issues, listen to the likes of Justin King, the former boss of Sainsbury’s, who told Radio 4’s Today programme last week: “There’s been terrible weather in the key sourcing locations for this veg at this time of year. But to understand the problem you have to go back further; this is a sector that has been significantly disrupted by Brexit.”

It is a message echoed by Pekka Pesonen, secretary general of the European farming organisation Copa, who talks of post-Brexit disruption to a food supply chain that involves a “highly integrated, highly complex set of measures across all operators, all regions, countries and even outside the Union. Disturbing this delicate balance, even if it’s a minor change to the supply routes and supply chains, it may have a significant impact, through operators that opt for the easier way somewhere else.”

And then we have Alfonso Gálvez of the Spanish farming union Asaja, who told the Guardian: “There have been logistics and transport problems when it comes to export, such as a shortage of lorry drivers to service the UK market, and the problems we’ve seen with the queues to get into the country through Eurotunnel. On top of that, you’ve got the costs of all this bureaucracy and all these waits, which mean that perhaps the UK market isn’t so attractive.”

These views – and the fact that the government decided not to extend its energy support to this sector, leaving greenhouses and polytunnels across the country cold and empty – are the truth about these shortages. Brexit is not the key factor, but it is adding to the chaos, and Europe is not suffering as we are, despite what the “nothing to do with Brexit” brigade might have you believe.

Delays at the border, red tape and a shortage of HGV drivers are all down to Brexit and have made the food logistics industry less resilient, flexible, and reliable. The industry certainly feels that its suppliers are concentrating on providing what produce they do have to customers on the Continent rather than to what some see as a small market on a remote northern island.

But that is not the major issue here. I have been talking to the logistics industry, and it fears that these shortages could just be a warning of what lies ahead.

Shane Brennan, chief executive of the Cold Chain Federation, which represents the section of the logistical industry that transports chilled products like food, says: “This is a warning that getting product into the UK is not getting any easier. Erecting trade barriers through paperwork, which we are still due to do in the UK at the end of this year, will make problems like this worse in the future.”

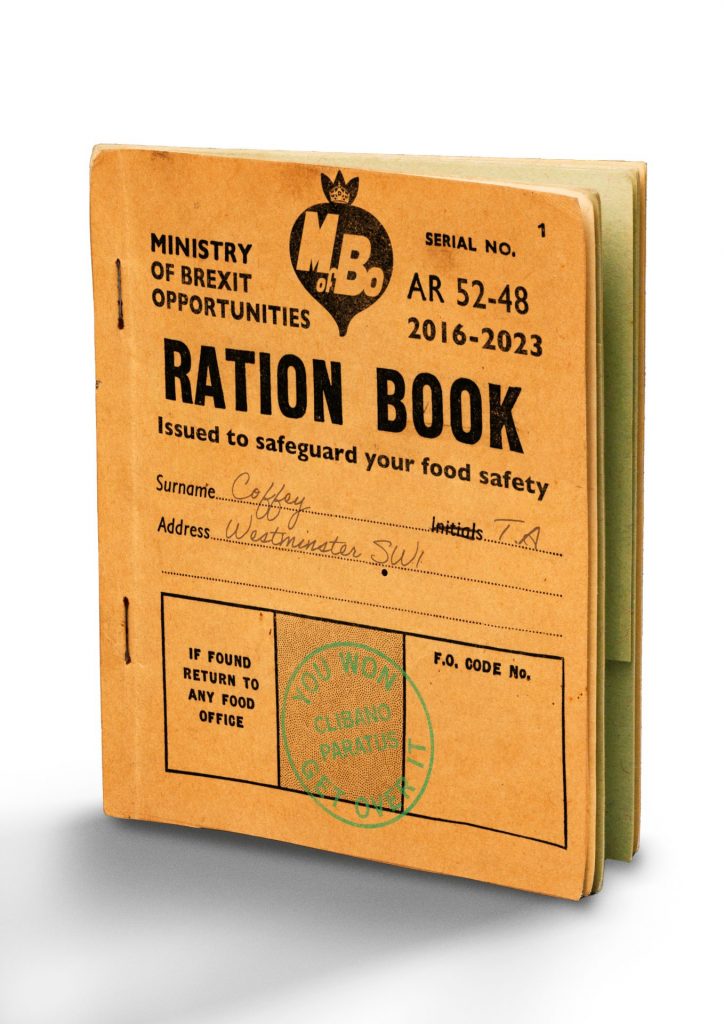

To understand the significance of those words, just cast your mind back to early last year. Food and fuel prices were soaring after the invasion of Ukraine and Jacob Rees-Mogg, then minister of state for the laughably titled Brexit Opportunities department, travelled to Dover to announce that checks on food entering the UK would be delayed for a fourth time, until the end of 2023, in order to save consumers the £1bn in annual costs they would incur. It looked and sounded like a surprisingly sensible delay at a time of rising inflation.

The checks are called SPS – it stands for Sanitary and Phytosanitary – and they cover everything from looking for insects in imports of plants to meat and dairy quality. They cover the means of production, as well as animal welfare. Since they are viewed as being vitally important to keep diseases out of the country and ensure the standard of food, the government will have to introduce them sooner or later.

Indeed, that fourth delay in introducing the checks left the farming industry aghast. Spot checks have already revealed that sub-standard meat is entering the country, and the industry is terrified that the failure to inspect imports properly could lead to an outbreak of African swine fever or another highly contagious and devastating disease. But the government insisted that at a time of rising prices, it would be madness to introduce checks at the UK’s borders.

But the real reason for the delay to the checks is now becoming clearer. Brennan says that when they come – and they are now just eight months away – they will cause a huge problem. The current shortages are just a small sign of what may lie ahead.

As he explains, when those new controls were expected to be introduced last year: “We were clear at that time that this would have collapsed a significant part of the food supply chain into the UK.”

In short, if you’re seeing nothing on the shelves now, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

Funnily enough, the real issue would not be with fruit and veg, which are not heavily checked. The problems would arise mainly with meat and dairy products and anything containing either.

They not only require extensive checking, many need to be approved by vets as well. But the main problem, as Brennan told me, is “because of what we call groupage. That is small business loads, with more than one customer on the same lorry – (the customers) would have faced significant additional costs and disruption and they would have just stopped doing it. We know that would have happened because it is what happened to exports when the EU introduced the same controls” on UK exports to the EU in 2021.

Then, Brennan says, the industry saw “an immediate collapse of groupage, small business exports. It was during Covid, but they never came back. We still have a third fewer exporters than we did before the erection of these SPS control borders from the UK to the EU. And there was nothing about what was being proposed by the UK government – going into July of last year – that meant it would have been any different going the other way.”

In fact, Brennan says the problems could be even more severe for UK importers this time than they were for UK exporters back then: “If anything, it would potentially be worse; we are three to four years into the change now, the small businesses scattered across the whole European continent aren’t necessarily expecting now that there will be any changes to the rules, because Brexit is done.”

Brennan knows this because that is what small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) on the Continent told him. “The feedback we were getting from our small EU customers was that if it is that much of a hassle we would not just bother selling in the UK – ‘we will just not service that market’.”

In short, thousands of SME food companies on the Continent would have just stopped supplying the UK. The system would have ground to a halt.

The problem is far less serious with major suppliers who can place one yet unified load on one lorry with one lot of red tape. With groupage, no one knows what else the lorry is carrying, and the uncertainty of delay alone will be a massive burden.

That means that not just fresh fruit and veg would have been in short supply. The UK imports almost half the food it consumes every day.

The government is supposed to be trying to address the problem by devising a new system that would not empty the supermarket shelves of the UK overnight. When it delayed introducing them last year, it said it would use the time to put in place a new digitised system for customs and sanitary checks by “accelerating our transformative programme to digitise Britain’s borders, harnessing new technologies and data to reduce friction and costs for businesses and consumers”.

But that was the fourth such delay and it didn’t manage to create a new system during any of the previous three delays.

Perhaps because this is exactly the same kind of new magic technology that was supposed to make a border in Northern Ireland invisible, and negate the need for new facilities at the UK’s ports. The technology does not yet exist and, if history is any guide, will never exist. The government’s plans were expected to be announced at the start of the year, but the industry is still waiting.

But it is difficult to see what the UK government can do; it has had seven years to come up with a solution that works and so far it has failed. It must introduce these tests and checks sooner or later, because the dangers of another food scandal like the horsemeat one or, even worse, an outbreak of a disease like foot and mouth, are just too high.

But if it cannot find a way to introduce these SPS checks without creating exactly the same delays and damage to business that the EU did when it introduced them on UK exports, a large part of the UK’s food imports could just grind to a halt.

The shortage of a few tomatoes and cucumbers on the shelves in midwinter could well be looked back on with nostalgia. Or, more likely, as a warning that was ignored.