The Zentralstadion in Leipzig was partly built from the rubble and debris left after much of the city had been heavily bombed during world war two.

The 100,000-capacity sports venue opened in 1956 and was demolished in 2004 to make way for what is now known as the Red Bull Arena. But as Aston Villa’s travelling supporters might have discovered when they beat RB Leipzig in a 3-2 thriller on December 10, two monuments from 1956 still remain.

One is the Zentralstadion’s old main building and the other is a 150 ft-tall tower named in honour of Werner Seelenbinder, also known as the wrestler who fought the Nazis.

Seelenbinder’s name should feature in any list, video or article about athletes turned activists, but rarely does, and his name was all but erased from history in the old West Germany. Yet, through the efforts of a professor and a group of football supporters, Seelenbinder’s extraordinary story is being discovered by a new audience.

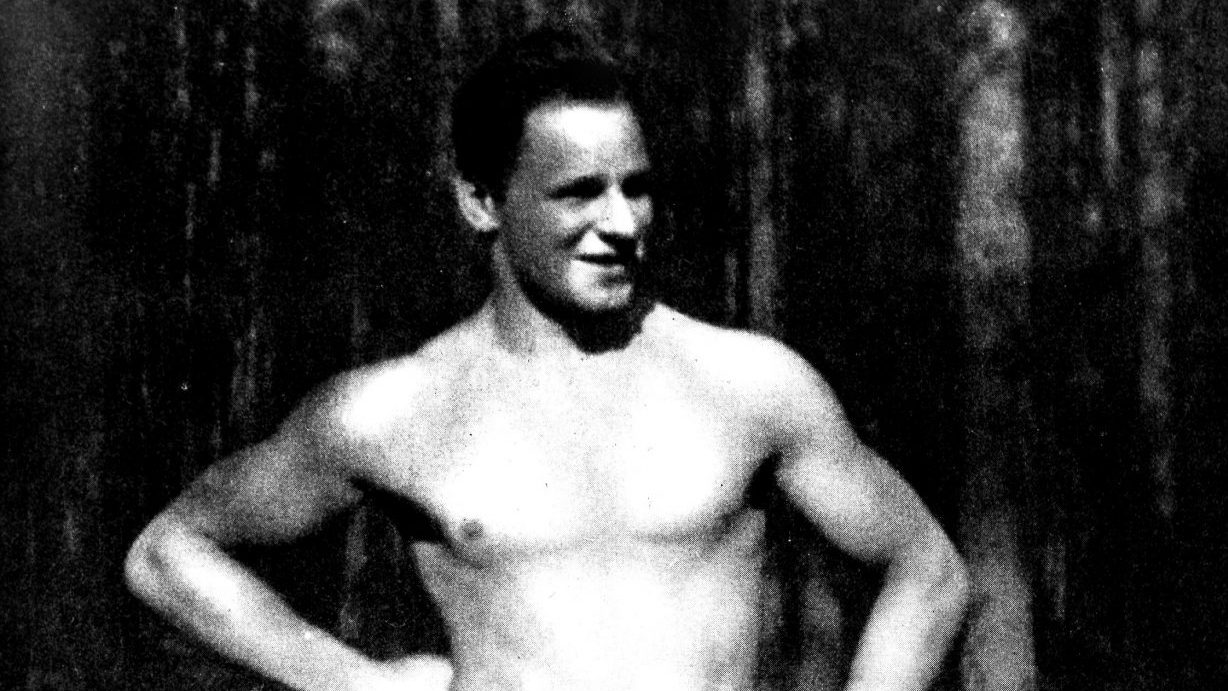

He was born 120 years ago, trained to be a wrestler at Sparta Lichtenberg in Berlin, a workers’ sports club, and became a member of the Communist Party in 1928. He would go on to be Germany’s top wrestler, and even had a move named after him known as ‘Der Seelenbinder’.

He was also one of very few public figures to openly oppose the Nazis – when Seelenbinder won a national title in 1933 he refused to give the Hitler salute. Seelenbinder intended to repeat this act of defiance if he won a medal at the Berlin Olympics in 1936 and ranked among the favourites in the light-heavyweight category. It would have given him the sort of legacy afforded to Tommie Smith and John Carlos who gave the Black Power salute on the podium at the ‘68 Olympics.

“Werner had already been targeted by the state authorities for refusing to give the Hitler salute (in 1933),” explains Dr. Oliver Rump, a professor of museology and museum management at HTW Berlin.

“As a result, he was denied a professional coach, as is customary in Olympic teams, and even private accommodation and limited catering could not prepare him optimally for the Olympic Games. He could only prepare for the competitions with his work colleagues and party comrades on the mat on his employer’s premises,” he adds.

Seelenbinder finished fourth. No medal, no podium and no chance of making a statement to the world.

By the time the war started, Seelenbinder had joined the Uhrig Group, an underground resistance movement whose mission was to try and weaken support for the Nazis. “(He) was involved in transporting and distributing illegal leaflets, smuggling confidential information abroad as a travelling sports cadre and helping to provide underground accommodation for comrades and secure illegal gatherings,” Rump explains.

The State Secret Police (Gestapo) infiltrated the group and Seelenbinder was imprisoned in 1942. Over the next 20 months he was interrogated, tortured and then finally executed – beheaded with an axe – in Brandenburg-Görden Prison on October 24, 1944.

In a farewell letter sent to his father, Seelenbinder wrote, “The times I had with you were great, and I lived on them during my incarceration, and wished back that wonderful time. Sadly fate has now decided differently, after a long time of suffering. But I know that I have found a place in all your hearts and in the hearts of many sports followers, a place where I will always hold my ground. This knowledge makes me proud and strong and will not let me be weak in my last moments.”

In East Germany, he would become a symbol of resistance. Schools, holiday camps, streets, stadiums and buildings were named in his honour. His face also appeared on stamps.

Being a communist from Berlin made for a complicated legacy. He never received any recognition in the West, and following the fall of the Berlin Wall Seelenbinder’s name was also in danger of disappearing from the public consciousness in the East.

“I had known the story of Werner Seelebinder since my school days in the 1980s, when I was allowed to visit the GDR and the sports stadium in Leipzig as a “youth tourist” from West Germany, but then he virtually disappeared from my memory. It was not present in West Germany,” says Rump.

“When I noticed that memorial plaques to Werner Seelenbinder had been damaged or even stolen in the district around my university, HTW Berlin, in East Berlin – the district of Köpenick was the seat of the National Democratic Party of Germany/NPD (now “Die Heimat”) – it was clear to me that his legacy must not be allowed to disappear or must be disseminated.”

Rump has been touring Germany with a new exhibition titled Werner Seelenbinder – Wrestler, Communist, Enemy of the State. The last stop on that tour was Leipzig.

Even though Seelenbinder didn’t have any direct connection to the area, Rump calls it “a city of athletes” and Seelenbinder is celebrated here especially among a group of RB Leipzig supporters/activists known as Rasenballisten.

It is often assumed, wrongly, that the RB stands for the club’s owner Red Bull, but is short for RasenBallsport – a made-up title given to the club when it was founded in 2009, as sponsor names are not permitted in German professional football. The name is hardly ever used by RB Leipzig itself, so Rasenballisten was created to emphasise the club’s roots in the city and its identity beyond the big brand sponsor.

“Our members are as diverse as our fan community. What unites us is our passion for RasenBallsport, the city of Leipzig and living out our fanhood far beyond the stadium,” says spokesperson Graham Kaufmann.

“In our opinion, the stadium is also a space in which social issues are addressed and therefore also a political place. At many different levels – in work within committees, dialogues with the club and also in events we organise – we work to fight racism, anti-Semitism and other forms of discrimination as well as sexualised violence, which is also a major problem area in the football context.”

Seven years ago, Rasenballisten published the first copy of their fanzine and called it Der Seelenbinder. Kaufmann says: “When we started producing the Seelenbinder fanzine at the beginning of 2017, the name Werner Seelenbinder was almost unknown in our fan community. The plate commemorating him was first renewed at the end of 2019. For us, naming the fanzine after Seelenbinder was thus a first attempt to draw attention to his name, his connection to our stadium and his life story.”

The story of a man who took a stand against the rise of the far right resonates with an audience concerned about the growing support for political parties like the AfD and who see football as a gateway to inform and educate.

Kaufmann adds: “In our opinion, the diversity of the players on the pitch, the diversity of the people in the stands and the shared enthusiasm for one’s own club make football a place where values such as democracy, diversity and solidarity can be taught, especially to young people.

“We believe this is particularly important in our stadium, as many children and young people from relatively small towns and rural areas in eastern Germany – precisely where the AfD is strongest – come to our home matches.”

Rump also belives there is much to be learned from Seelenbinder’s life. “Sport and culture are becoming an asset to be defended with ever scarcer financial resources, and that’s a good thing! I am pleased that young people, who we also address at our university, are open to the difficult topics of anti-fascism, workers’ sport and prevention against right-wing forces here, or were even sensitive to them beforehand.

“Please do not misunderstand, of course not that young people should sacrifice their lives, but in the sense that it must be prevented from ever happening again! May his life, his fate be a warning.”