There were four of the 24 hours to go at Le Mans and the Iron Dames were starting to believe. Having started 14th in class, the only all-female team in the World Endurance Championship (WEC) had scythed through the field and were heading for their maiden victory in the most important race of the year. After two second-in-class finishes in 2022 – they finished the season in third – could this be their moment?

Well, so much for Lady Luck. The brakes on the Dames’ Porsche brakes began to fade. By the final hour of the race they were shot and the car headed to the pits for replacements. When the chequered flag fell, the Dames had sunk to fourth.

When that first-ever win finally comes, it will be quite the coup. For a sport that, ostensibly at least, allows men and women to compete on equal terms, the historical representation of females in motor racing is woeful. Of almost 800 drivers who have started a Formula 1 World Championship Grand Prix, only two have been women. “There are females out there who can go all the way in Formula 1,” the Iron Dames’ Danish driver Michelle Gatting told the BBC earlier this year. “There have been barriers – including sponsors not being able to get their heads around women driving a car – but they’re getting fewer.”

But while Formula 1 is often considered the apogee of world motorsport, there are tens of thousands of racing fans who disagree. For them, endurance racing is the true test of driver and machine.

And they will add that the very pinnacle is the race that takes place in the Sarthe region of France every June. It’s considered to be the greatest, the most exacting, and the most prestigious motorsport event on the planet. It is the Vingt-Quatres Heures du Mans or, in English, the Le Mans 24-Hour race. And this year it celebrated its centenary.

Before the race, all the talk was of the Iron Dames finally breaking their duck. To win at Le Mans in its 100th year would have yielded the perfect coda to their story.

And while everything is relative, compared to Formula 1 the 24-hour race has a far longer history of female participation. Sixty-five women have competed at Le Mans over its 100 years out of almost 1,500 drivers who have taken part. But despite the townspeople of the French resort of La Baule who, upon hearing that women would be competing in the 1971 race, declared in a now rather risible letter to the organisers that Le Mans “is a man’s race, we don’t want drivers who wear skirts”, there have been notable successes down the decades.

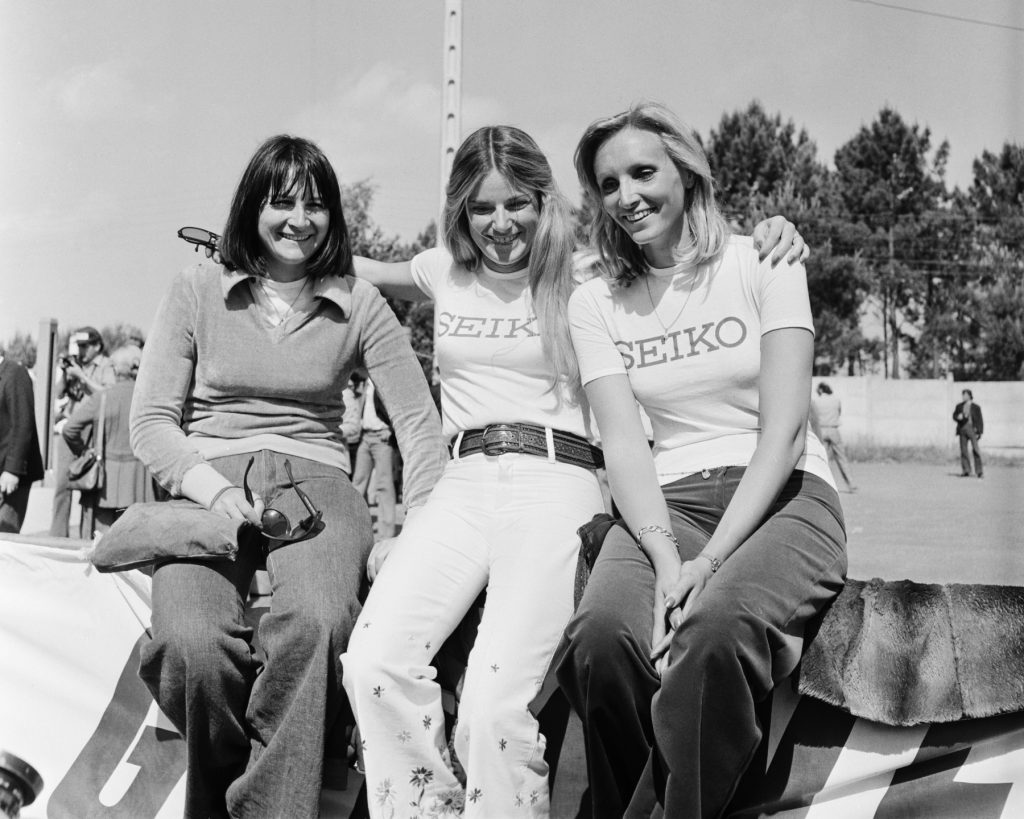

No woman has won overall victory but there have been class wins including two by all-female crews. The Ecurie Seiko team of Belgians Christine Beckers, Yvette Fontaine and Frenchwoman Marie Laurent won the 2-litre class in 1974, and the following year the all-French team of Christine Dacremont, Marianne Hoepfner and Michèle Mouton – the only woman to win a World Championship Rally – took their Moynet-Simca LM75 to victory in the same class.

“In 1973 we had been the race’s first retirement,” recalls Beckers. “Typically the press described us as scatterbrained because of fuelling strategy errors. So it was great to return and win the following year.”

In 1977 Beckers shared a car with Italian Lella Lombardi, the only woman to score a Formula 1 World Championship point. Even male sceptics were impressed when, after her car expired on track, Beckers jumped out and repaired it, as you are allowed to do in endurance racing. “I had to strip the electrical wiring with my teeth,” she says.

Beckers was following in illustrious tyre tracks. The first women to compete at Le Mans were Odette Siko and Marguerite Mareuse of France in 1930. Siko, as part of an otherwise male team, would share the 2-litre class victory in 1932 and finish fourth overall, still the highest placing for a woman in the race’s history. 1935 saw the highest number of female starters to date: 10.

However, a moratorium was imposed in 1957 – by which time 27 women had taken part – following Annie Bousquet’s fatal accident at the 12 Hours of Reims, the previous year. The restriction on females wasn’t lifted until 1971 – the year of the disconcerting La Baule letter – when Marie-Claude Beaumont was part of the Corvette team. No skirt in sight, she wore a racing suit just like all the other drivers, so presumably the residents of La Baule were becalmed.

“There was a lot of what today we’d call sexism,” remembers Beaumont. “Quips, either joking or demeaning. But the fact I was there at all attracted attention which was a starting point for women in motorsport. Novelty value I guess.”

Nobody did more to dispel that novelty value than Annie-Charlotte Verney, a local woman, who started 10 consecutive races beginning in 1974, finishing sixth in 1981, the best overall post-war result by a woman.

The Iron Dames compete in the Grand Touring Endurance (GTE) class – one of three categories in this year’s championship. All cars are crewed by teams of three drivers who share stints and Gatting was joined in the car at Le Mans by Belgian Sarah Bovy and Swiss Rahel Frey.

In 1974, Beckers, Fontaine and Laurent were the only finishers in their class. At Le Mans, the Iron Dames were racing against 20 other rivals.

But still, the omens had been good. In addition to their two championship second places last season, the Iron Dames took victory in the Portimão 4-Hours European Le Mans Series race in Portugal and won the Spa-Francorchamps 24-Hour GT3 race in Belgium. They were also on pole position at the 1000 Miles of Sebring race this year in Florida.

But Le Mans is a world apart and a very cruel place, as the Dames discovered. First, there’s the small matter of getting through those gruelling 24 hours.

The GTE class was the slowest of the three categories of cars taking the start at 4pm on Saturday 10th June. Ahead of them – and very quickly behind them as they start to be lapped – were the two classes of fast sports prototypes competing for overall victory. This means GTE drivers constantly need to be aware of blue lights and flags waved trackside by marshals, and radio messages indicating they are about to be overtaken by faster cars.

At speeds topping 300 kilometres an hour, move the wrong way to let one pass and calamity ensues, as François Perrodo discovered last year when his Ferrari moved into the path of Alexander Sims’s Corvette. The video is on YouTube. Fortunately, everyone involved walked away, but it’s why so many cars never make it through the night

Tom Kristensen, who has won Le Mans a record nine times describes driving there as like concentrating for 24 hours on a maths exam while simultaneously fighting a boxing match. And when night falls, or the weather is inclement, then the jeopardy is doubled. The headlights of faster cars zip past before they are barely registered. Windscreen wipers struggle to shift the weight of water and judging braking for Le Mans’s notorious chicanes and tight corners becomes increasingly problematic.

Avoid mistakes, make it through to dawn on Sunday and still 12 hours remain. Make it to midday and teams start to think that victory, with four hours to run, is perhaps a possibility. Which is exactly the position the Iron Dames found themselves in as Sunday afternoon approached. But Le Mans invariably saves its legendary iniquity for the final laps, as they learned to their cost.

Deborah Mayer is founder and CEO of the Iron Dames project, a role she combines with being president of the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile’s Women in Motorsport Commission. Before the race, she had hedged her bets. “We can win of course,” she said. “And we can also lose. Either way, it’s my passion to see the Iron Dames fulfil their potential.”

Mayer previously worked in finance. But she’d always had a love of motorsport and was determined to bring her experiences of one competitive industry to bear on another.

“It’s obvious to everybody there are talented women drivers out there,” she added. “We have some of the best. That’s why we are running at the front of the grid in every event. And it’s not just on the track, walk around the paddock and look at the talented female engineers, mechanics, team managers. Just because we had victory snatched away this time makes no difference to what we, and they, are hoping to achieve.”

One of those drivers she signed up is Gatting, whose stellar reputation in the paddock is hard-earned. “I struggled with the sexism at first,” she says. “It’s better today – we have shown how good we are – but back then I was angry; fighting battles on and off the track. I heard people were afraid of meeting me. But I earned respect.”

She too tempered her despondency with the Le Mans result: “After being at the top for so long, it was tough to see a brake change steal everything, although obviously safety comes before anything else. I am still proud.” Bovy admitted to being “super-disappointed”. It was, she said, “a painful outcome for all of us.”

But disappointment at this year’s Le Mans aside, are the Iron Dames actually making progress on and off the track in changing attitudes to females in motorsport?

“Yes. Slowly,” says Frey. “And we do that by showing we are the equal of all the other teams and drivers. Sometimes I think the guys see us in their mirrors and decide they can’t let us by. It hurts their self-esteem. It must hurt a lot, because we pass them a lot,” she laughs.

Bovy believes the reason women were slow to arrive in motorsport is because “when young kids start out in go-karting it’s seen as a ‘boys’ sport. They have no role models. And the women you did see in motorsport were often scantily clad ‘grid girls’. Accessories to the main thing. We’re changing that.”

WEC dropped grid girls almost a decade ago, regarding them as an anachronism.

Mayer agrees with Bovy that enlarging the base at a young age will make the difference. “I’m sure more women will get to the top. But to do so we need to create the structure which allows them to shine,” she says. “It’s a long-term process.”

Formula 1 has set up an all-female racing series called F1 Academy which intends to identify women who can make the transition to the top categories. Why it might succeed where the previous all-female championship, the W Series, failed is unclear.

The German driver Sophia Flörsch, who has competed for the Iron Dames, is adamant it’s the wrong way to go. “I agree with the arguments, but disagree with the solution,” she says. “Women in direct competition with men is the crucial factor.”

And, arguably, the entire point of the Iron Dames project. Christine Beckers believes now is the time for a woman to win again at Le Mans. “Stamina and ability are what’s required,” she says. “We had these attributes in the 1970s too, but now attitudes have shifted.”

Whether victory by the Iron Dames in Le Mans’ centenary race would have been more significant than that of 1975 or any that preceded it is a moot question. But they intend to return next year with lessons learnt.

After all, 100 is just a number. The glass ceiling can wait 12 more months to be broken. And when, inevitably, it is, it will be another victory on the road to equality for every other dame who takes to the track.