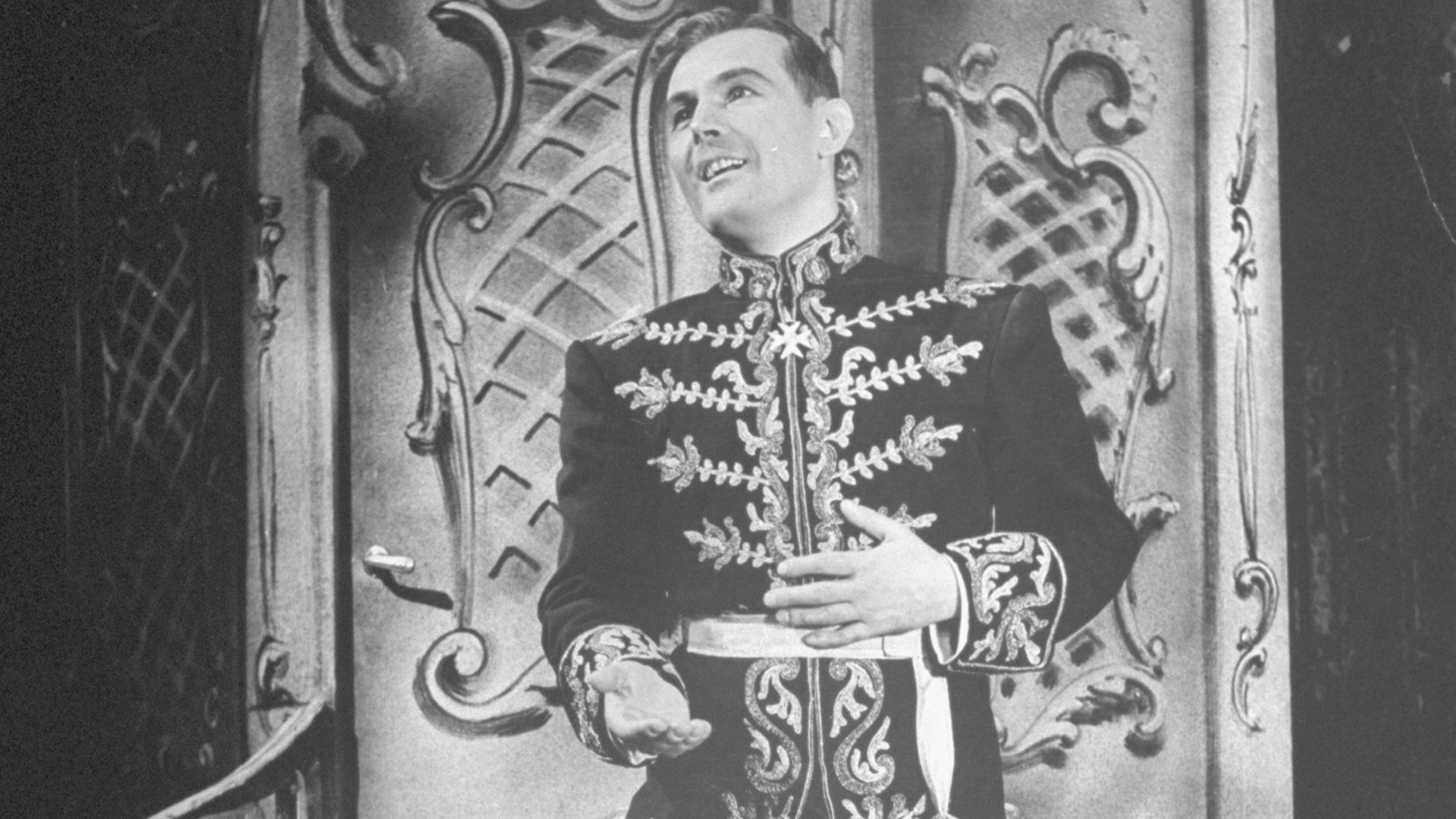

In the year Valentino died, another star of early cinema was making his first moves towards a career on the silver screen. Polish tenor Jan Kiepura, who had the same dark good looks as the then recently lamented Italian-born film star, made his debut in the silent film O czym się nie myśli (The Unthinkable) in 1926, and while his name would not echo down the years

to quite the same extent as Valentino’s, Kiepura is far from forgotten.

Every summer for the past 55 years the southern Polish spa town of Krynica-Zdrój has held a festival in Kiepura’s name – the celebrations for the 120th anniversary of his birth took place last week with performances by native talents Aleksandra Kurzak and Rafał Bartmiński – and he is remembered both as a world-class musical talent and a Polish hero. His story is one that both reflected and defied the Polish experience of the early 20th century.

Kiepura was born in Sosnowiec, a town that stood where the lands of the three empires that carved up Poland in the partitions met. His formative years came just as the new Polish Republic emerged from the chaos of the first world war, and he was just 17 when he took up arms in the first Silesian

uprising, trying to wrest control of the region from Germany. In 1921 he went to study law in Warsaw just as the city was entering a new golden age.

But Kiepura knew from choir singing as a youth that he had a god-given voice and he took singing lessons in Warsaw. He was just 22 when he made his operatic solo debut and by 1930 he had performed in Vienna and Paris and landed a contract at Milan’s La Scala.

Kiepura began to be spoken of as the ‘Polish Caruso’, but he was controversial for his informality and his habit of taking to balconies or car roofs in impromptu performances. Yet his ability to break down the barrier

between performer and audience meant he was a shoo-in as a leading man as the talkie arrived. Films in Italy and Germany were followed by a contract with Paramount and the 1936 Hollywood film Give Us This Night.

But that year was even more significant for Kiepura’s marriage to the remarkable Hungarian-born singer and actress Marta Eggerth. Shortly before Eggerth died in 2013 aged 101, she called Kiepura “the only love I ever had in my life,” and as the outbreak of war forced the couple to leave Europe for the US in 1939, their careers would become just as entwined as their personal lives.

The war years saw Eggerth land a contract with MGM and appear with Judy Garland, while Kiepura sang with the New York Metropolitan Opera. But

the pair’s greatest success came in 1943 when they starred together on Broadway in Franz Lehár’s operetta The Merry Widow. They would perform it throughout America and Europe in English, French, German and Italian versions for the next two decades.

Kiepura and Eggerth moved to Paris and resumed their European film careers after the war, but a return to Europe did not mean a return home for Kiepura. Despite having gone to France after the fall of Poland to support the Polish army in exile, and worked tirelessly for Polish refugees throughout the war, Kiepura was referred to as a traitor by the Communist authorities and he had to wait until Stalin’s death and the political thaw before he could finally go back. His 1958 visit saw him receive a hero’s welcome.

When Kiepura died of a sudden heart attack in 1966, his body was returned

to Poland. Today he stands as a legend of inter-war Polish culture, and he was celebrated as such in Krynica last week.

Kiepura’s connection to Krynica came in the early 1930s when he commissioned modernist architect Bohdan Pniewski to build him a hotel. Resplendent in steel and marble, it was the height of modern luxury and symbolised a pace of life and a Polish progressivism that was soon to be

shattered by war. Operated as a sanatorium by the Nazis and then by the Communist state, the building has now returned to its original function

and is a tangible monument to the man who created it.

Kiepura named his hotel “Patria” – “homeland”. It was fitting, for while he

was forced to flee Poland and made a dream life elsewhere, it was a life that

was always bound to the fate of his country.

JAN KIEPURA in five songs

Ob blond, ob braun

Kiepura declared “Ob blond, ob braun, ich liebe alle Frauen!” (“Blondes, brunettes, I love all women!”), in this title song of the 1935 German film he starred in.

Mein herz ruft immer nach dir

Written by Austrian composer Robert Stoltz, My Heart Always Calls Out to You was the gushingly romantic title song of the 1934 film on the set of which Kiepura met the love of his life, Marta Eggerth.

Che gelida manina

Kiepura starred as struggling poet Rudolfo in Puccini’s La bohème in his New York Metropolitan Opera debut in 1938. This aria is sung when his character first meets doomed love interest Mimi.

Usta milczą, dusza śpiewa

This piece is from the Polish language version of The Merry Widow, the

operetta that Kiepura and his wife performed thousands of times across

Europe and the US in the 1940s and 50s.

Di quella pira

Kiepura performed this piece from Verdi’s Il trovatore in Give Us This Night (1936), his Hollywood debut.