First and last, the Velvet Underground will be associated with New York City: with the shadows and speed of the crumbling Lower East Side of the mid-60s, where the group formed; with the silver foil of Andy Warhol’s Factory, where they first brushed fame; with standing on the corner of 125th Street and Lexington Avenue, waiting. The pulsing sense of the city scraping against and rushing through their sound was there from the first. You can already feel it in Lou Reed: Words And Music, May 1965, a fascinating album of demos released this month, featuring the earliest-known recordings of Reed and Velvets’ co-founder, John Cale, performing embryonic versions of songs that would forge their legend when they appeared in radically mutated guises two years later on their debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico.

At the same time as the release of May 1965, however, comes the coincidental arrival of another significant addition to the VU library, one that underlines how, although famously commercially unsuccessful during the group’s lifetime, this music would echo far beyond Manhattan. Linger On: The Velvet Underground is a sumptuous new book compiling over 40 years’ worth of reportage by one of the band’s most assiduous chroniclers, Spanish

journalist Ignacio Juliá. Beginning in 1979 – nine years after Reed brought the Velvets’ curtain down by quitting the group – Juliá has returned repeatedly to the VU, conducting lively interviews with all core members: Reed, Cale, the irreplaceable guitarist Sterling Morrison and matchless drummer Moe Tucker; as well as Nico, who augmented their best-known lineup as chanteuse; and Doug Yule, the often-undervalued substitute drafted in after Reed engineered Cale’s expulsion in 1968.

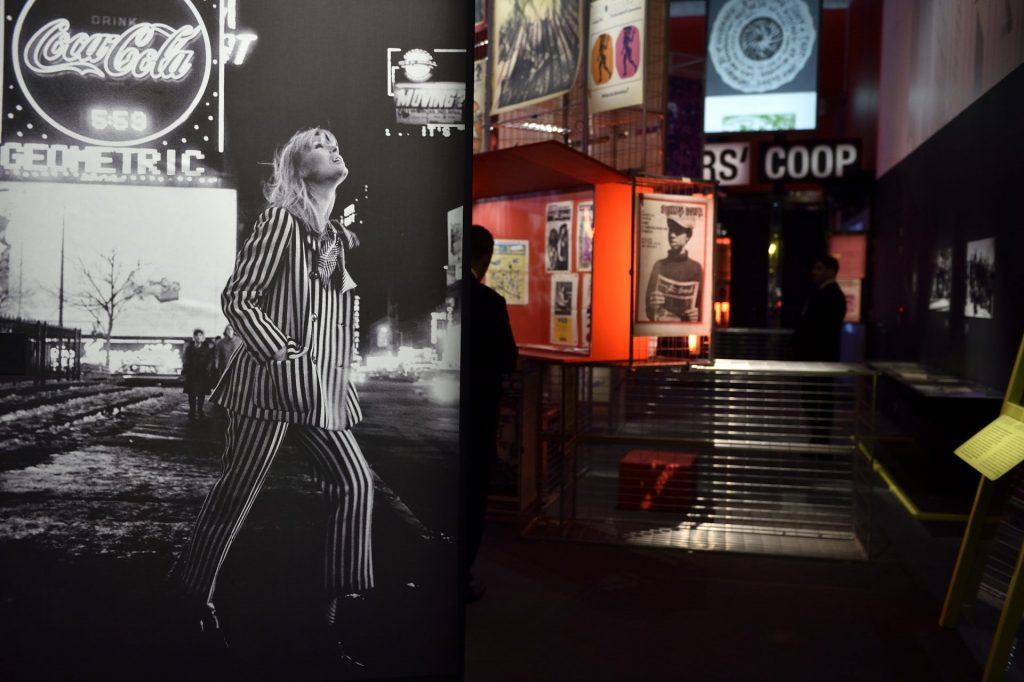

The Barcelona-born Juliá’s near-obsessive dedication illustrates a point – one previously highlighted in 2016, when the world’s first large-scale exhibition devoted to the group, The Velvet Underground: New York Extravaganza, opened at La Philharmonie de Paris, drawing over 65,000 visitors. As the quintessential sunglasses-after-dark New York punks, the Velvets have provided deathless inspiration to succeeding waves of American bands. Yet it is arguably in Europe they spawned their most fervent fans, and unquestionably in Europe their music had its most profound impact. In Europe, too, the Velvet Underground were ultimately destined to mount their last stand.

Perhaps that’s a reflection of how strong, stray strands of European influence helped to form the VU from the beginning. That starts, of course, with the extraordinary Welshman abroad, John Cale himself.

The May 1965 tape captures Cale and Reed just five months after their first astronomically unlikely meeting, two young outsiders born one week and 3,000 miles apart in March 1942: the Brooklyn-born Reed an accountant’s son obsessed with poetry and rock and roll; Cale raised amid a landscape of work, religion, standing stones and tales of witches in the rural village of Garnant, south Wales, the only child of a coal miner and a primary school teacher, who escaped the valley through sheer talent and bloody-minded will.

By the time he reached New York in 1963, Cale had burned through a lifetime’s worth of European musical experience. Prodigiously gifted since childhood – he’d been broadcast performing his own Khachaturian-inspired piano composition on BBC radio aged around 11 – by 13 he was violist with the Welsh Youth Orchestra, with which he toured the Netherlands. Soaking up the BBC’s Third Programme, ordering scores through the local Workingmen’s Library, he became drawn to the modernist line – Schoenberg, Webern, Stockhausen – and when he won a scholarship to Goldsmiths College in London, chafed against the rigidly classical teaching to seek out one of the UK’s leading experimentalists, Cornelius Cardew, himself a former Stockhausen assistant.

Cardew kindled Cale’s fascination with the American leader of the contemporary pack, John Cage, and Cage’s mysterious successor on Manhattan’s cutting edge, La Monte Young. When Cale was awarded a Leonard Bernstein scholarship to study at Tanglewood, Massachusetts,

he left after a year and hightailed it instead to New York, working first with Cage, then joining Young’s fabled cosmic-minimalist project, the Dream Syndicate, entering the bohemian heart of the downtown scene.

Cale bonded with fellow Syndicate player Tony Conrad, taking a room in the same derelict apartment at 56 Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side. The friendship inadvertently led to the formation of the Velvet Underground when the pair were approached at a party by an executive from Pickwick Records, a company specialising in cheap rip-offs of current hits. He was seeking to assemble a fake group behind Pickwick’s young in-house writer, Lou Reed, to promote The Ostrich, a wild single Reed had recorded under the moniker The Primitives, and reckoned the long-haired avant-gardists had the Beatles-ish “commercial look” he needed.

Reed was a whizz at churning out the soundalikes Pickwick demanded, ersatz Motown one minute, bargain Beach Boys the next. But as they became friendly, he divulged to Cale he was more serious about a batch of songs the company refused to record. The contrarian Cale grew intrigued. Reed showed him lyrics including future VU classics Heroin and I’m Waiting For The Man. They recognised something in each other. Rock and roll was never the same again.

This is the era the May 1965 album preserves: Reed and Cale, armed with only an acoustic guitar, a harmonica, and the belief they could create something unlike anything anyone had ever heard. Reed’s folksy performance doesn’t yet know the dissonance and drone, the electrified

subway rumble and shriek Cale’s avant-garde training would unleash. But the Velvets’ sense of their own private New York is already tangible. In the liner notes, referring to the 56 Ludlow Street flat where Reed was soon spending all his time, the critic Greil Marcus describes it as: “The poverty in these songs – the bathtub-in-the-kitchen you hear in their clumsiness, the fifth-floor-walkup you can hear in their defiance.”

That coldwater tenement was a particular melting pot. Its inhabitants included another European émigré who had a significant, unsung effect

on the VU’s development, the poet and film-maker Piero Heliczer. Born in Rome in 1937 to a Polish father and German mother, Heliczer had been a child actor in Mussolini’s Italy. In 1944, his father, a doctor and resistance

leader, was executed by the Gestapo. After the war Heliczer bounced between New York and Europe, living in Paris, where in the late 1950s he

co-founded an experimental publishing imprint, the Dead Language Press.

Heliczer’s partner in Dead Language was his friend and fellow 56 Ludlow

tenant Angus MacLise, a poet-percussionist who became the still-unnamed Velvet Underground’s first drummer, in a lineup that now also included Sterling Morrison, whom Reed had known since both attended Syracuse University. (Morrison added his own Europhile spice: after leaving the Velvets, he started teaching at the University Of Texas and gained a PhD in medieval literature, writing studies on Beowulf and Old English poetry.)

In summer 1965, this anonymous VU accompanied Heliczer at a screening event for his experimental 8mm films at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque on 41st Street, a co-op run by Jonas Mekas, another European refugee: born in Lithuania in 1922, Mekas had lived through Soviet then Nazi occupation, and spent time in a German labour camp before reaching the US in 1949.

Heliczer’s multimedia happening simultaneously involved film, lights, slide projections and dancers, while the Velvets extemporised a live soundtrack. Soon, they were being called on to jam “strange music” for other Cinematheque associates. In a 1979 essay, Morrison cited the experience as a turning point: “The path ahead suddenly became clear – [we] could work on music that was different from ordinary rock and roll since Piero had given [us] a context to perform in.” Indeed, it was their connection with Mekas’s underground film scene that prompted the band to adopt the Velvet Underground name, after Conrad found a trashy sex-in-suburbia paperback of that title in a gutter.

It wasn’t the only turning point. It was through Heliczer the VU met Barbara Rubin, another independent film-maker, who in December 1965 brought the group – now in their definitive lineup, as Moe Tucker replaced MacLise with her inimitable heartbeat drumming – to the attention of Andy Warhol, who was seeking a band for his own multimedia happening, eventually dubbed the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI).

By the time Warhol became their ostensible manager, the Velvets had already almost given up on the US, feeling less affinity with American pop than British bands like the Kinks, the Small Faces and the Yardbirds, whose

aggressive singles Cale picked up on trips home. Early Velvets demos were

circulating around London, imported by Cale, Rubin and Heliczer’s wife,

Kate, in the hope of attracting a record label. “We had all but actually packed

up and gone to London,” Morrison commented in the seminal VU biography Uptight. “We would have been in London by spring 1966, come what may, had not the EPI happened.”

While Warhol’s intervention stopped the VU crossing the ocean, he would bring more European flavours to the mix. In public, the man born Andrew

Varchola played coy about his family background: “I come from nowhere.”

But behind the blank façade, the influence of the life his parents had known before the US was strong enough that, decades later, in Songs For Drella, the memorial song suite they composed after Warhol’s death in 1987, Reed and Cale commented on the “Czechoslovakian customs” of etiquette Warhol prized at the Factory.

Warhol considered his roots as Czech, and at home spoke with his mother in

what he thought was Czech. In fact, Warhol’s parents, emigres from Miková

in present-day Slovakia, were Carpatho-Rusyn, although they would not have

recognised the then-suppressed identity. They held strongly to their culture, and scholars have increasingly speculated on the influence on Warhol’s work of the religious folk art – icons, holy cards, crucifixes – that dominated the family home and the churches the privately devout artist attended.

Certainly, Warhol was in icon-making mode when he insisted on adding to the Velvets their most overtly European facet, Nico. Born Christa Päffgen in Köln in 1938, she was evasive about her background – her parents separated before she was born, and her father, a soldier, was killed in the war – but had already carved out her own legend, first as a model in Berlin and Paris, then a fleeting face in European cinema through an appearance in Federico Fellini’s 1960 state-of-the-decadence address, La Dolce Vita.

The Velvets grouched about her, but Nico’s look – glowing blonde in white mod suits against their surly black and biker boots – and Germanic vocals set

them apart from the American mainstream as much as anything else when Warhol unveiled the club happening he constructed around them, the EPI, originally staged near-nightly in April 1966.

In many ways, collaging film, lights and dance with the VU’s ear-splitting

performance, it was a bigger budget, louder, more pop sequel to their events with Heliczer. But thanks to Warhol’s star power, the residency would make the Velvets’ name in New York, garnering serious press and drawing A-listers like Jackie Kennedy. Fittingly, given the European currents around the group, the setting for this breakthrough was a rented hall in St Mark’s Place known as the Dom, aka the Polski Dom Narodowy – the Polish National Home.

The Velvets would continue to record nothing but astonishing music after April 1966, but the EPI marked the high-water mark of the band’s visibility during their brief existence. For a moment, the path into Europe seemed open. Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni wanted them for his existential mystery Blow-Up, being shot in London that October, but the travel expenses ruled them out. European offers came in, but Warhol was growing more interested in cinema again and made nothing of them. Most intriguing, the Beatles manager Brian Epstein became enamoured with the Velvets’ debut album in spring 1967 and made overtures towards signing them and organising a European tour – plans that ended with his sudden death that August.

Exacerbated by frustrations over low sales and lack of radio play, tensions built. The disheartened VU split first with Nico, then Warhol, and finally each other, when Reed forced Cale out in 1968 following their second, most extreme album, White Light/White Heat. The Mark II Velvets featuring Doug Yule recorded two more LPs, masterly in different modes, and became a formidable road band. But by the time Reed quit in 1970, the Velvets had never left North America.

It was their very elusiveness, their undergroundness, however, that saw

the VU’s cult spread across Europe during a period of unrest. In late-1960s

Germany, as the nation struggled with guilt and anger over its recent past, a

generation of bands drew inspiration from the Velvets. Living in a divided

country, they rejected mainstream English and American rock as much as

German history, and heard in the VU something untainted. The founders of

Can, Kraftwerk and Neu all cited the influence; indeed, bootleg recordings

of the Velvets’ Dom performances are eerily predictive of their kosmische musik sounds.

The Velvets’ most extraordinary legacy, however, grew in Czechoslovakia. In spring 1968, as the Communist regime tentatively eased restrictions, Prague playwright Václav Havel travelled to New York for the American debut of his play The Memorandum. While there, he bought White Light/ White Heat, knowing only it was “something unknown and unobtainable in our country”. Back in Prague after the Soviet invasion cracked down on reforms, tapes of his album circulated among dissidents as a totem of freedom, and inspired the formation of a band, the Plastic People of the Universe.

In 1976, most of the band were arrested for playing their outlawed music. The incident prompted Havel and other Czech intellectuals to formulate Charter 77, calling on the regime to respect international human rights agreements. Circulating the document was a political crime, and paved the way to the Velvet Revolution of 1989. One year later, in Prague, Lou Reed met Havel, now Czechoslovakia’s democratically elected president. Havel gave him a hand-printed book of Velvets lyrics in Czech, a samizdat from his dissident days. “They were very dangerous to have,” Havel told Reed. “People went to jail.”

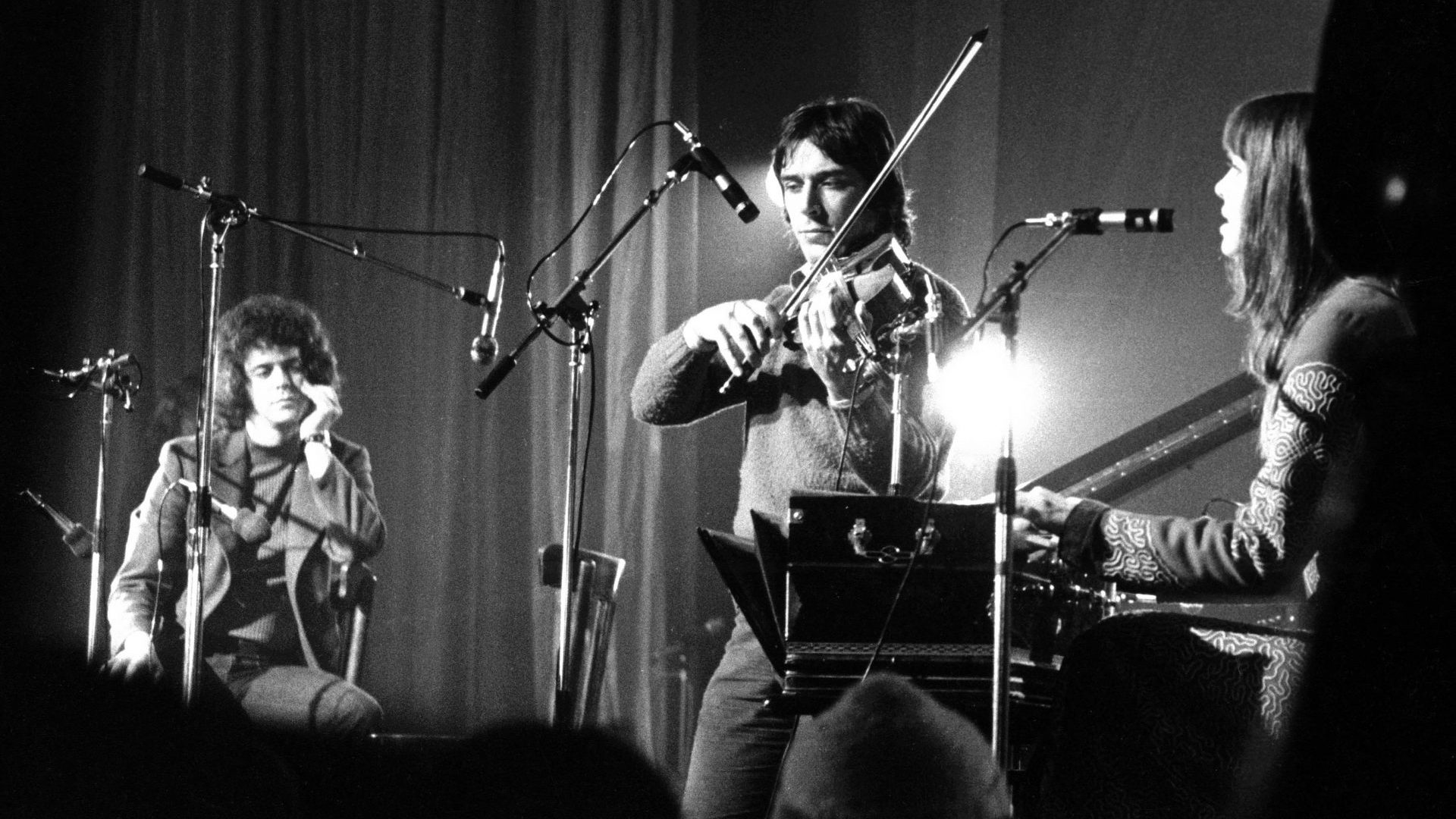

European fandom seemed almost to will the Velvets back into being. The first unlikely semi-reunion happened in Paris in January 1972, when Reed,

Cale and Nico performed a one-off acoustic show at Le Bataclan, a fragile

and magical performance filmed for French TV. But it wasn’t until 1990, in

France again, that the impossible happened. The Fondation Cartier, situated outside Paris in Jouy-en-Josas, asked Reed and Cale to perform selections from Songs For Drella to open a major Warhol exhibition. Also present among the Factory-era invitees were Morrison and Tucker, who, unexpectedly, spontaneously, joined them to play Heroin – a cautious, then racing, raging

performance that marked the first time all four had played together since

September 1968. “As I got off the stage,” Cale wrote afterwards, “I was on the point of tears.”

It led to the Velvets’ final chapter, in summer 1993, when the four formally

reunited for a European tour. Plans for subsequent American dates were

scrapped as old tensions saw Cale and Reed splitting in acrimony. Two years

later, in August 1995, Sterling Morrison died, and it could never be again.

Some say that brief European tour of 1993 was a disappointment. I’m not one

of them. I remember the opening night at Edinburgh’s Playhouse, the buzz of a crowd not believing this was actually happening. I remember the Velvet

Underground standing blinking into a five-minute ovation before they’d even

played a note. I remember them looking lost on the brink of discovery during Hey, Mr Rain. I remember The Black Angel’s Death Song sounding like nothing else. I remember for a moment, for everyone, that it felt like coming home.

Lou Reed Words And Music, May 1965 is out now on Light In The Attic records. Linger On: The Velvet Underground by Ignacio Juliá is published by Ecstatic Peace Library

Damien Love is a journalist specialising in music, films and TV