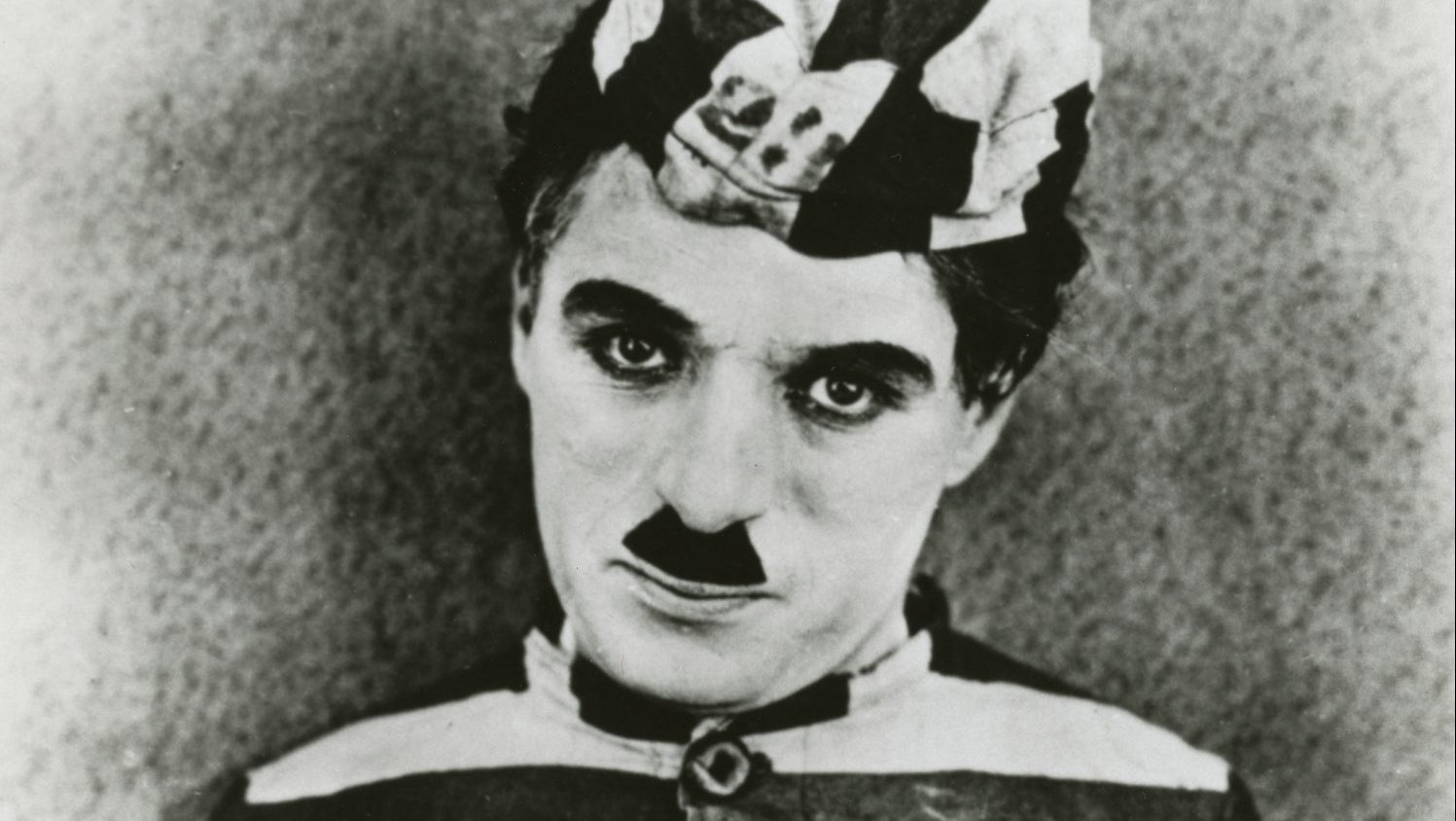

Everyone did Charlie Chaplin. The bow-legged walk, the twirl of the cane, the tilt of the head, the twitch of the moustache, the comic shrug of the

shoulders and the tip of the hat, real or imaginary. There was a once a story

going around that the real Charlie Chaplin had entered a lookalike contest and finished in 20th place.

And everyone thought they knew Charlie Chaplin. When the 20th century roared into its full modernity, he was the most famous person on earth.

But of course, the fame and the adulation, the huge crowds that stretched for city blocks on end, thronging to glimpse a tiny figure wherever he went, these weren’t really for Charlie Chaplin. They were for a character he’d created, sometimes called The Tramp or The Little Man or, by Chaplin himself, “the little fellow”.

As a new documentary arrives, we find ourselves asking again who both

these figures were, The Tramp and the real Charlie Chaplin, and marvelling at the enduring iconography of what is still – despite Darth Vader, ET, Marilyn Monroe, John Wayne and the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe – cinema’s most recognisable character.

The Tramp had no name or address, no job or family. The man behind the costume, however, was also just as unknowable. According to Peter Middleton, one of the co-directors of The Real Charlie Chaplin, they are sides of the same coin, a sort of “before and after” snapshot of the amazing rags-to-riches story of Chaplin’s real life.

“He went from practically Dickensian slum poverty on the streets of south London to unimaginable wealth and global fame in about 10 years,” says Middleton. “He was probably the first person to ever do that, an arc made possible by the coming of modernity, newsreels, media and the cult of celebrity. If Chaplin himself was a product of the new world order, The Tramp was the part of him who had arrived in America off the boat to become this symbol of the giant new dream factories springing up in Hollywood.”

I’d never quite realised the everyman power of The Tramp. To the millions of immigrants flocking to America, the huddled masses, here is their reflection on screen: a migrant, even a vagrant, with no nation nor language yet who speaks to everyone, or as the voiceover by Pearl Mackie in the film puts it: “A nobody who belongs to everybody”.

No wonder he became such a popular figure – he was all of us and the world took this little man to its heart. Carlitos, Charlot, they all had their own name for him, a pet name, something endearing like you’d call a best mate, the part of you who’d do things you couldn’t or wouldn’t dare.

Hulton Archive/Getty

“There’s a restlessness about this character even on his very first appearance in 1914,” says Middleton, referring to a short for Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios called The Kid Auto Race and shot during an actual go-kart meet in Venice, Los Angeles. It is uncanny just how familiar the character feels to us already, even on this first glimpse of him, as he gazes back at us, as if looking for some kind of reaction. He looks as if he’s growing into the clothes – and the medium of movies – right before our eyes, looking down the lens, breaking cinematic rules before they’ve even been really established, toying with us, until he walks off, practically fully formed, to become the biggest star in the world.

“The little fellow is always renewed and refreshed each time we see him from this point on,” says Middleton. “He’s a fireman, next a dancer, then a

policeman or a boxer. Mischief is a foundational aspect of him, but he’s

always checking in with us to let us know he’s on our side.”

The film’s theory is that The Tramp was entwined with Chaplin’s own London upbringing in Walworth, where he was born in 1889 – a few

days after the Eiffel Tower was opened in Paris and, eerily, just a few days

before the birth of Adolf Hitler.

It was a sad childhood, his beloved mother succumbing to mental illness

and his music-hall performer father disappearing when he was five years

old. The film conjures up how it might have sounded by using the voice of

Effie Wisdom, as recorded in the 1980s by the film historian Kevin Brownlow, an interview reconstructed here with Effie played and lip-synched by actor Anne Rosenfeld. Effie’s is the most wonderful London accent, the sort that has now largely disappeared.

“Oh I used to play with Charlie as a boy, back of the Lambeth Walk,” she

gossips. “Well, he used to talk common, like I did, dropped his aitches ’n’ all that.”

These early years are more than formative. They never leave Chaplin and, in the closing stages, the documentary brilliantly reveals how the buildings and alleys of Lambeth repeatedly show up in Chaplin’s films, such as The Kid and in City Lights, meticulously reconstructed by the director on Hollywood sound stages.

It’s a densely packed documentary, attempting to chart and decipher a life and a creation that had such extraordinary impact. It’s hard to single out the salient moments but the film deserves credit for digging deep into Chaplin’s troubled relationships with women. There are headlines and court transcripts making him sound a most unsavoury lover and husband, a serial adulterer who flies into rages. His four marriages were all to much younger women, 16-year-olds mainly, and he needed subterfuge and media power to get away with it.

Witness troubling footage of a 1993 interview with Lita Grey (his second wife) explaining how she was ignored and shunned and made to feel insane. There’s just as much evidence pointing to how the general public, too, have no desire to see any fault in their hero.

As co-director James Spinney says: “He was the first celebrity who was totally bound up in a character and he was certainly the first star to have

these personal issues made public. But people had fallen in love with The

Tramp, saw themselves represented in this everyman character and of course at first didn’t want to square that with hearing about these rather

horrendous accusations women were levelling at the person behind their

favourite films.”

And so we come to Hitler, and the uncanny closeness Chaplin shares with him, not just the birthdates and the moustache. The relationship is something that becomes most explicit in The Great Dictator of 1940, when the

Tramp character (taking the form of a Jewish barber) is mistaken for the dictator Adenoid Hynkel. As the documentary points out: silence was

Chaplin’s medium but sound was the making of Hitler, the ferocity of his

oration crackling out on newsreels.

Successful as it was, The Great Dictator was also the end of The Tramp and, ironically, Chaplin’s long speech for tolerance at the end of the movie became one of his most famous and talked-about scenes, after a lifetime of

silence. It was also the beginning of the end. It’s as if the disguise of The

Tramp kept the real Chaplin hidden, and when he began to talk and to appear as himself, the relationship with his audiences unravelled. He was

accused of communism.

It seems very sudden, but when he left America for the premiere of his film Limelight in London in 1952, Chaplin was told he would not be welcomed back. He was forced into exile, his “moral worth” called into such question by America that he felt compelled to flee. He found a huge home in Switzerland, in Vevey, and some peace with a new young lover, Oona O’Neill, daughter of the American playwright Eugene O’Neill. When they met, she was 17, he was 52.

The last part of the film uses home movies to show Chaplin with his new

family, which ran to eight children including Jane, Michael, Christopher

and Geraldine. His children tell us what he was like as a father and the

reports aren’t entirely favourable.

This later part is also where he conducts a 1967 interview with Life magazine writer Richard Merryman, the audio of which is used extensively in the new film to reconstruct the scene, using the actual room where it was recorded and photographed at the Chaplins’ home, Manoir de Ban.

Spinney and Middleton worked on the audio taken from the interview master tapes – never intended for broadcast – to bring it to up to scratch and, again, had actors play Chaplin and his interviewer, lip-synching to the original audio. “To hear his voice echo again around this huge lounge was very eerie,” recalls Middleton. “It was ghostly and scary, but we felt this was a way of seeing and hearing Chaplin at a key stage of his life, looking back. But there’s always the doubt: can we trust anything he says?”

So, the search for the real Charlie Chaplin is a poignant one. It’s as if he throws you off the scent at every turn, and while he leaves Lambeth and embarks on a stratospheric journey, Effie Wisdom stays on earth, making

tea in exactly the same place.

“In the end,” says Spinney, “we had to show where the gaps were. The more we looked for the real Charlie, the more elusive he became… like he was trying to thwart us.”

Chaplin did return to America, once, to receive an honorary Oscar in 1972,

but by the time he visited London, in 1975, he was too frail to get out of his

wheelchair to receive his knighthood from the Queen.

Charlie Chaplin died on Christmas Day 1977. Without doubt it is The Tramp, who lives on. And twirling his cane, twitching his moustache and shrugging off all that life can throw at him, the tragedy and the comedy, it’s likely The Tramp will outlive us all.