At the time when the English language first left the British Isles to cross the North Atlantic Ocean during the 1600s, Norwich in Norfolk was the second largest urban area in England. Ipswich in Suffolk was the seventh largest, Norfolk’s Great Yarmouth the eighth, Cambridge the 10th, and Colchester in Essex the 12th.

It would not be surprising, then, to find that East Anglian English played an important role in the formation of North American English, and the other new Colonial Englishes which were soon to develop in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. There is quite a lot of evidence to suggest that this was in fact the case, especially for the USA.

We know that the early American settlement by the so-called “Pilgrim Fathers” in Plymouth, Massachusetts, which began in 1620, had considerable East Anglian involvement.

The New England area of the north-eastern USA – the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut – today bears very many place names which are also East Anglian toponyms, presumably brought across the ocean by homesick English people: Ipswich, Massachusetts, dates from the 1630s, while both Norwich and Colchester in Vermont were settled in 1763.

Other Norfolk-origin names in New England include Attleboro [Attleborough], Burnham, Hingham, Lynn, Newmarket, Norfolk, Norwich, Thetford, Windham [Wymondham], Wolcott [Walcott], and Yarmouth. Suffolk names in modern New England include Brandon, Haverhill, Holbrook and Wenham; from Essex we find, among others, Braintree and Dedham; and from Cambridgeshire there are Cambridge and Ely.

Of course, this is only suggestive of heavy East Anglian settlement of the area. But we do know that the Pilgrim Fathers who founded the eastern New England Massachusetts colony predominantly came from the radical Puritan eastern counties of England, and that a high proportion of the adult pilgrims on the Mayflower who settled the Plymouth Colony were from Norfolk and Essex.

It would be surprising if this pattern of immigration had not had some linguistic consequences, and there is good evidence that it did. For instance, the typical East Anglian pronunciation of “room” and “broom” with the short vowel of “good” is also typical of New England. The use of typically East Anglian verb-forms without an s-ending, such as “he like,” “she say,” “it come,” also found its way into a number of American varieties.

And it also seems rather likely that East Anglian dialects were involved in the development of the “yod-dropping” which is widespread in North America. “Yod” is the name which is often given to the consonantal sound represented in English spelling by the letter y in words such as yes, yacht, young.

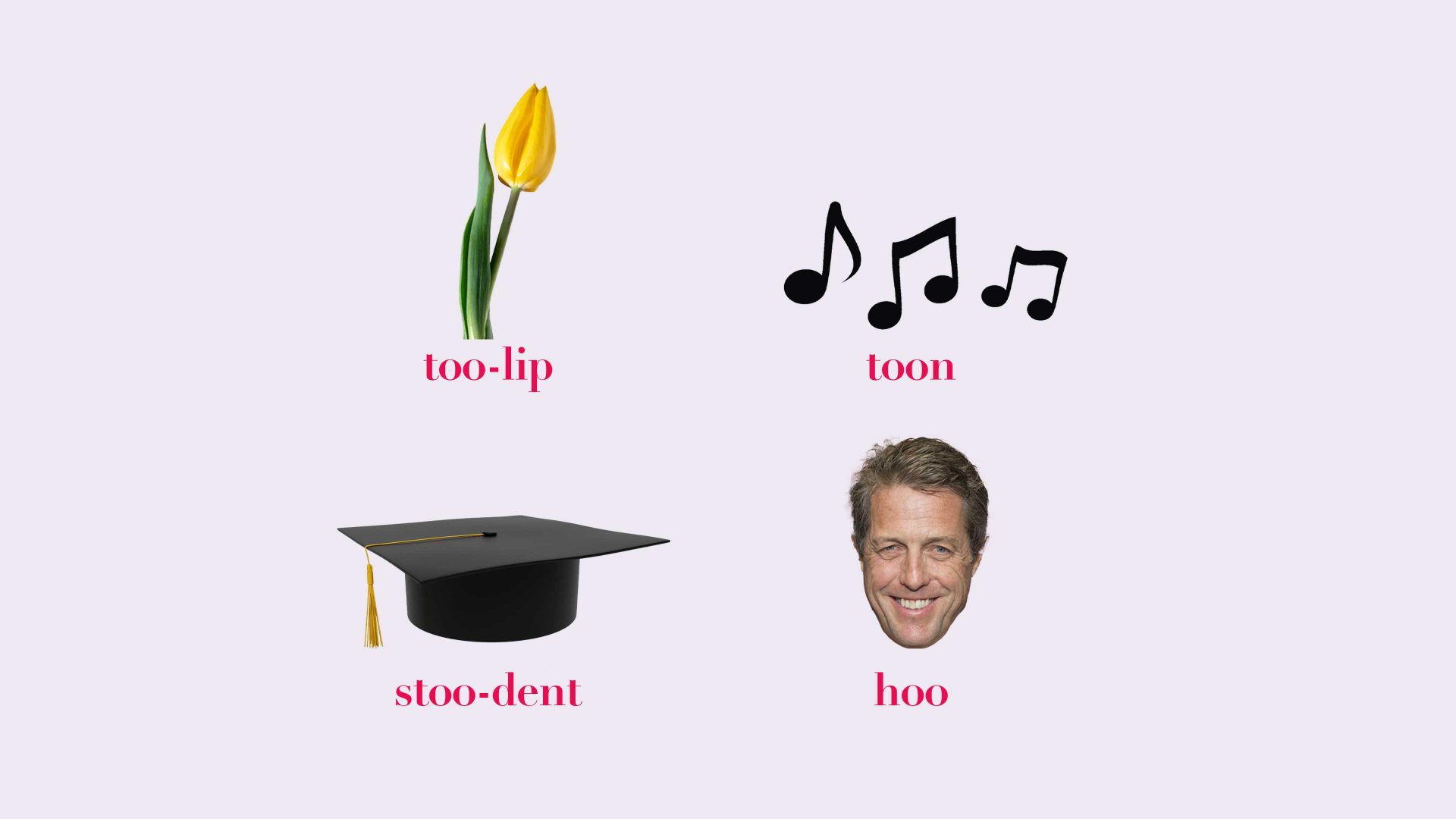

The term “yod-dropping” refers to the fact that in most modern American accents, there is no yod, no y-sound, after t, d, and n in words such as tune, student, duke, news. Many Americans pronounce tulip as “too-lip”, whereas in Britain most people say “tyoo-lip” – unless they say “chew-lip”.

Since the departure of the English language for North America, yod-

dropping continued to spread in East Anglian English so that it occurs after other consonants than t,d,n, so in some accents today, yod has been lost even in vocabulary items such as cue, huge, music and view. In my own Norfolk accent I pronounce Hugh and who the same. And many people will have heard Norfolkman Bernard Matthews advertising his famous “bootiful’’ turkeys.

Connecticut

Unlike New Hampshire and Rhode Island, the names Massachusetts and Connecticut are both derived from Native American Algonquian languages. Massachusetts is thought to come from the Algonquin word “Massadchu-es-et,” meaning “great-hill-small-place”, while Connecticut probably derives from a Mohegan-Pequot word meaning “long tidal river”.