Peignoirs hang from carcass bones, swollen bellies merge into little houses, uncanny three-headed portrait busts stitched from pieces of tapestry sneer

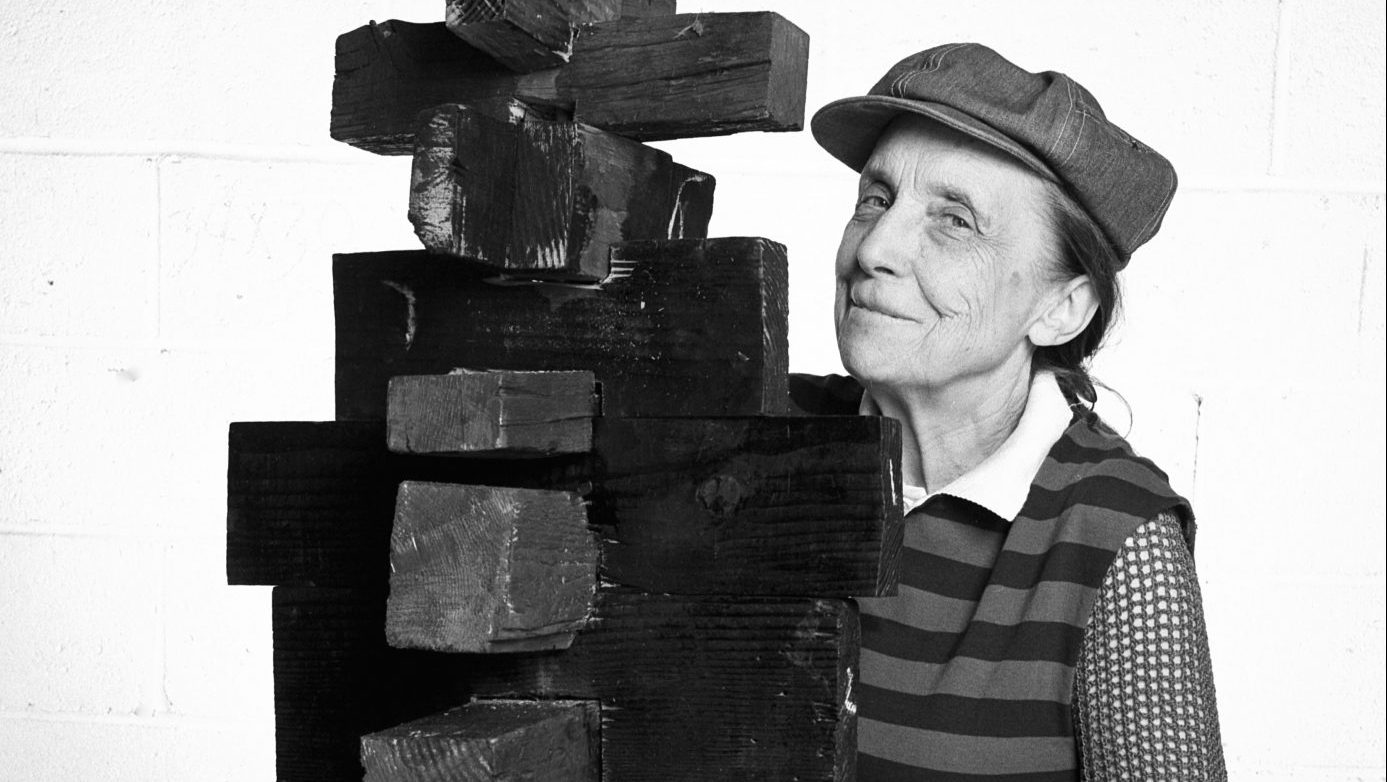

from plinths, while spools, bobbins and metallic spiders both spin and hold thread in tension. These are some of the macabre materials of the Hayward Gallery’s exhibition of Louise Bourgeois’s late works in The Woven Child, a compendium of the French American artist’s creative output over the last two prolific decades of her career until her death in 2010 aged 98.

Bourgeois was born in Paris but emigrated to the US with her husband, the art critic Robert Goldwater, in 1938, settling in New York, which was to become the heart of the abstract-expressionist movement after the second world war. There she exhibited her work alongside the key protagonists of the avant-garde art scene such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Arshile Gorky, but her art (which frequently speaks to the complexity of female experience) was overshadowed by the male-dominated currents of 20th-century art.

Despite her prolific output, Bourgeois wasn’t granted serious international recognition until she turned 70 in 1982, when the Museum of Modern Art in New York staged the first institutional retrospective of her work. Now, 40 years after her first major show, there’s still a sense of making up for lost time as the enthusiasm (and auction prices) for her art continues to swell. This spring the Hayward Gallery’s London show is joined by an even more sprawling exploration of the artist with Louise Bourgeois x Jenny Holzer: The Violence of Handwriting Across a Page, which runs at the Kunstmuseum in Basel until mid-May.

The Hayward show focuses on Bourgeois’s work in cloth and fabric from the final chapter of her career – a medium traditionally overlooked within histories of “fine art” for its association with the feminine, domesticity and the less prestigious category of “craft”. While feminist art of the later 20th century tried to reclaim and subvert the gendered associations with textiles and embroidery, for Bourgeois it was more acutely autobiographical – the artist’s parents owned a tapestry repair atelier just outside of Paris, where she grew up surrounded by industrious stitching, repairing and weaving.

In Respite, the earliest sculpture in the show, from 1992, is a giant armature stacked with bobbins and spools holding threads at different intervals ready to feed an industrial sewing machine. The elusive title suggests the composure and stillness that sewing and stitching brought the artist as she unstitched and reconfigured the fabric of her past, while the black threads become the metaphorical threads of her personal autobiography, held in tension at different points.

In her 80s, Bourgeois turned to her collection of fabrics, amassed over the course of her lifetime, from her own and her mother’s clothes, to her

trousseau of household linen, which she set about transforming into

sculptural installations and abstract collages. Stuffed bodies and orphaned

limbs in homely fabrics such as pink jersey and towelling contrast the

naivety of the material with psychologically darker possibilities, as they evoke mutilation and disfigurement. Elsewhere, intact items of clothing eerily call up the longabsent bodies that once wore them.

Bourgeois had an acute sense of how fabric and cloth act as containers for

emotions and memories, of how they wrap and enclose the body, registering

sensations and narratives that become wicked into their weave. It’s an angle

that makes the work in this show more easily comprehensible; after all, who

doesn’t weep at packing away the little clothes of a child since grown, or have an item of clothing that jolts them back in time to a long-evaporated

moment of joy?

Freudian symbolism and psychodrama inform many of the works in the show – Bourgeois was among the first generation to have come of age after the advent of psychoanalysis provided new tools for thinking about interior worlds of the individual. Quotes embedded into textile collages refer to “the return of the repressed”; large glass vitrines reminiscent of Victorian taxidermy tableaux hold stuffed-cloth bodies in embraces, some with prosthetic limbs (wall texts describe how these represent Freud’s concept of the “primal scene”, or the child’s first glimpse, real or imagined, of adult

lovemaking as a form of violence).

Bourgeois uses the literal and figurative fabric of her past and its traumas, unstitching and restitching it in an act of therapeutic repair and reconfiguration. One seminal trauma that she compulsively returns to is her

father’s affair with the artist’s adored young governess companion, who

moved into her parent’s marital bed. In Cell XXV (The view of the world of the

jealous wife) from 2001, two dresses and a blouse hang suspended on limbless, headless mannequins in a steel cage staging a claustrophobic, neurotic love triangle of betrayal and desire.

The real topic in this exhibition, however, is mothering, a theme that Bourgeois eviscerates across the course of her career, often depicting it as an

ambivalent and sometimes dark art. In Do Not Abandon Me, a baby dangles

from the body of its mother on an umbilical cord, both figures rendered in a raw fleshy shade of pink. Encased here in a glass vitrine, they call up both preserved anatomical specimens and the co-dependency of the mother-child relationship (who ultimately clings to whom?) Elsewhere, a stuffed sculpture of a supine female torso in white felt with a little house perched on its belly (part of a series called “Femme Maison”) is a comment on the entrapment of women inside the home as well as a view of the mother’s body as a welcoming hearth.

Everywhere the metaphor of weaving, crafting, spinning thread is linked to the act of creation in the maternal body. This is rendered most of all in the recurring spider motif for which Bourgeois is best known.

Deep into the exhibition, rounding a corner at the top of the stairs to the

second floor, we come face to face with a gargantuan bronze arachnid in the

corner of the room, nestling another of the “cell” structures beneath the cathedral-like arches of its eight legs. Inside dangles a bottle of her mother’s

favourite perfume, while tapestry fragments paper the sides in a reference to her family’s atelier. For Bourgeois the spider was not a threat but a benevolent presence whom she likened often to her adored mother, the silent and supple weaver who repaired and renewed not only tapestries but also the emotional wounds of her children. But while the spider protects her young eggs, the potential of horror is never far – here we see the mother as both refuge and cage, her nurture tempered by a terrifying potential to suffocate and entrap. Finally, the spider was also an alter-ego of the artist, who also weaved and stitched by drawing out from the substance of herself.

True to Bourgeois’s Freudian influences, the show mounts a compulsive, obsessive repetition on themes, striking the same note over and over so that by the last room there’s no second-guessing the artist’s accessible and readable take on the horror of human sexuality, dependency and psychology.

Meanwhile, in Switzerland the Kunstmuseum in Basel is staging a very different type of show. Louise Bourgeois x Jenny Holzer: The Violence of Handwriting Across a Page (until May 15) plays with the art museum’s traditional strategies of interpretation and display as Bourgeois’s vast archive

of writing, diaries, letters and artworks provide the playground for the American artist Jenny Holzer, who creates something of a homage to her late friend and role model. Holzer and Bourgeois first met in the 1980s and developed a lasting friendship, albeit at a respectful distance, the younger

artist describing her friend as “intelligent, determined, obsessive, furious and infinite”.

Across nine rooms, each with their own theme, Holzer eschews a chronological format in favour of an “intuitive logic”, pairing works in

unexpected juxtapositions and with a non-conventional use of space. Known

for her LED projections and use of text, Holzer also experiments with digital

technology and sound to create a more immersive experience, including a

unique augmented-reality app designed in collaboration with London-based creative innovation agency Holition. The sprawling nature of the exhibition even overflows into the Kunstmuseum’s permanent collection, where Holzer has curated a selection of Bourgeois’s works in dialogue with the historical collection.

Here, another riff of Femme Maison, this time in smooth, polished marble,

invites formal comparison with the buxom bathers of Cezanne’s Cinq Baigneuses; while the melancholy cadaver of old master Hans Holbein the

Younger’s Dead Christ in the Tomb is set against Three Horizontals, three soft

sculpture stitched forms of anonymous female bodies in a horizontal stack.

Similar recurrent themes of motherhood, loneliness, trauma and psychological horror are also present, among these Bourgeois’s Destruction of

the Father from 1974, an installation of mutton bones and animal parts cast in latex to represent a fantasy revenge scene from a cannibalistic feast in which mother and daughter have devoured an overbearing father.

Holzer explains Bourgeois’s trailblazing impact in simple terms: “She did as well or better than any artist in any time”. This vast output means she joins the ranks of the few artists who have enough work to more than fill two major European shows at the same time. The spider may long have been

swept out of the shadows, but as these two exhibitions confirm, we’re still held stunned and intrigued in her sticky web.

Catherine McCormack writes and lectures on art. She is the author of Women in the Picture: Women, Art and the Power of Looking and teaches art history at Sotheby’s Institute and the University of Oxford