The prime minister was there. The leader of the opposition was there. The mayor of London was there. Pol Roger was being poured by the gallon, the air heady with the scent of a thousand flowers. How better to spend a warm midsummer evening than at the pop-up court of the Sun King?

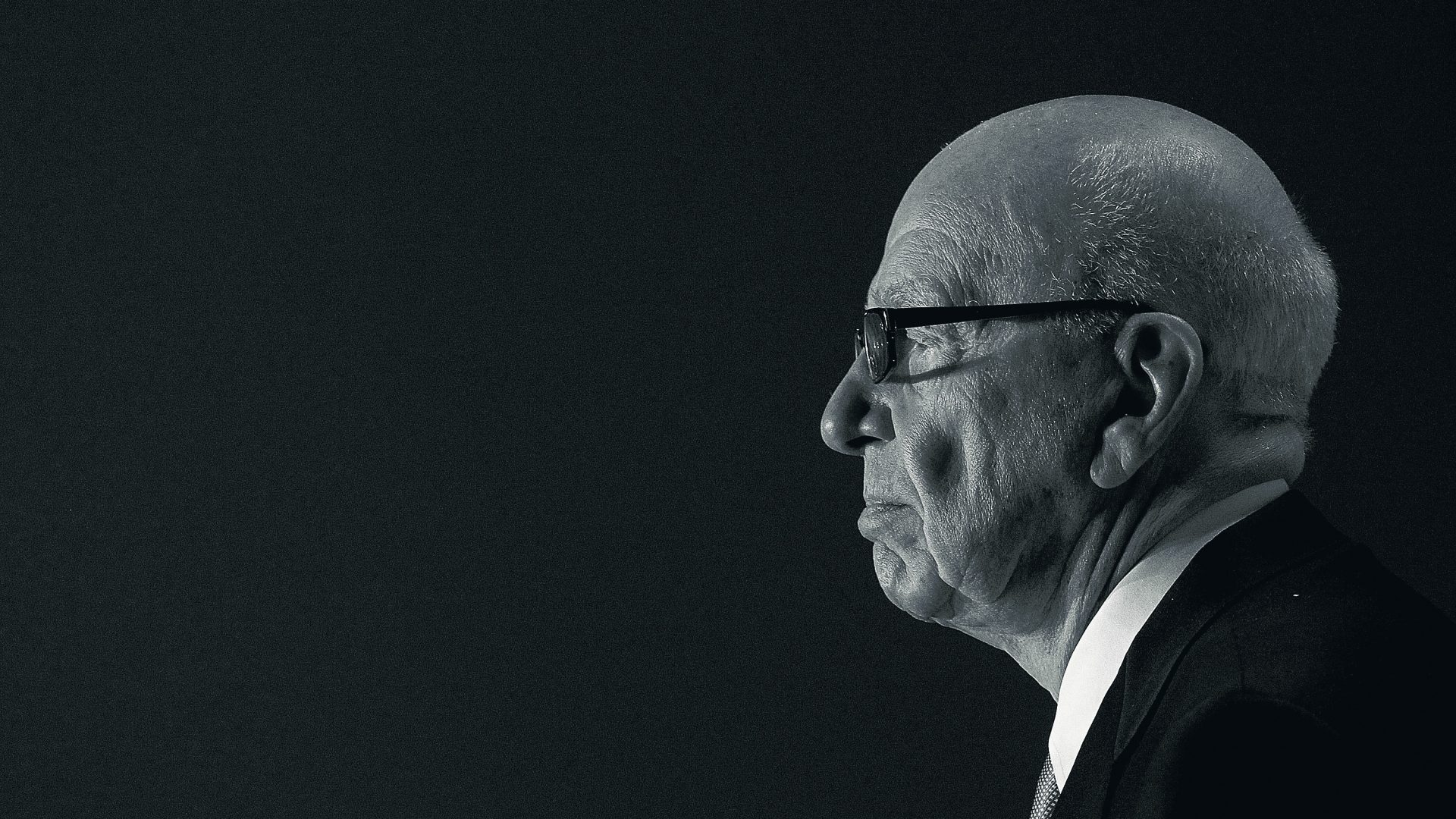

The venue was prestigious – Spencer House in St James’s – and the guests were powerful. For this was Rupert Murdoch’s summer party, the annual reaffirmation that when this 92-year-old Australian-turned-American swoops in with his entourage, the people who run Britain – or would like to – will scurry to pay homage.

Back in 2011, the Leveson inquiry was set up to examine the culture and practices of the press after the Guardian disclosed that Murdoch’s journalists had hacked the phone of murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler. The second part of that inquiry was supposed to look into the relationships between the press, politicians and the police. It was quietly dropped. To some eyes, Murdoch’s recent bash was both proof that it was needed and an explanation for why it never happened.

Half the cabinet was there, along with Liz Truss and two other former Tory leaders, plus Labour’s Rachel Reeves and Wes Streeting. Also present was a heavyweight battalion of newspaper editors and their top political writers. It was the ultimate networking opportunity – but do politicians still need to cultivate the press in this digital age when print circulations are in savage decline and parties can fire their message directly to the voter on any one of a dozen social platforms without any editorial filter or glad-handing?

Rishi Sunak may have thought it worth his while. The Mail is still hankering for Boris Johnson (not among the guests), but despite all the new incumbent’s troubles, the Johnsonite Sun is beginning to warm to the prime minister. Sunak may have wanted to woo Paul Dacre of the Mail and consolidate his relationship with Victoria Newton, editor of the Sun. When you’re 25 points behind in the polls a year before an election, you need all the help you can get.

The week before the party, the Sun’s Kate Ferguson had been alongside Sunak when he joined police on an early morning raid on a property suspected of housing illegal immigrants. There were no immigrants, illegal or otherwise, to be found. Still, the paper put together a spread in which Sunak roamed across a range of topics, from the boats to trans rights.

But what did Sir Keir Starmer, Rachel Reeves and Sadiq Khan think they could achieve by going to Murdoch’s party, beyond winding up the left of their own party, who will be even more enraged by a News Corp executive telling the Observer that the wooing is being done not by Murdoch but by Starmer. “We can’t keep him away,” said the source.

In 1995, Tony Blair travelled 10,000 miles to deliver the keynote speech to a Murdoch corporate gathering on Hayman Island off Queensland. At the time, Murdoch was growing weary of John Major’s clapped-out administration. Blair’s speech was a hit, and in March 1997, two months before the general election, the Sun backed him. Did Labour need that endorsement? Given the subsequent landslide, it’s more likely that Murdoch simply backed the favourite. But Blair described the speech as an unmissable opportunity.

Starmer’s three-and-a-half mile journey from Islington was hardly in the same league. He wasn’t speaking to a captive audience that was already in the market to buy what he had to sell. The tabloid contingent at the party had made up its mind about him years ago – they will do all in their power to keep him out of office.

What’s more, Starmer had ostensibly made up his mind about Murdoch long ago – his leadership campaign video featured the Wapping strike and footage of Murdoch alongside Rebekah Brooks during the hacking scandal. And even if that were all in the past, did he think it appropriate to accept hospitality from a man whose Fox News has just paid record libel damages in the US for claiming US voting machines were rigged against Trump, a man being sued by a royal prince in Britain, a man whose Australian news organisations are under fire for climate change disinformation?

Whatever Starmer’s thinking, his appearance at the party seemed as forlorn an exercise as his “We’re not reversing Brexit” article for the Express (reportedly offered to and rejected by the Mail). His piece was given a straight heading but then countered by a lot of Brexiteers saying: “You can’t trust him”, including a rival opinion piece by Tory deputy chairman Lee Anderson.

More understandable are the half a dozen articles and readers’ Q&As Starmer has done for the Mirror over the past couple of years. Although that seems almost sluggish compared with Sunak’s output for the Telegraph – he’s written nine articles in the past year, three of them on migration.

Both leaders still seem to believe in the power and influence of the press – but are they right to? When Blair made that trip to Australia, the Sun was selling nearly 4m copies a day and the four News International titles had a combined sale of more than 10m. Today, many news organisations have stopped publishing audited figures, but in a recent exercise for the trade website Press Gazette, Bron Maher concluded that our national daily and Sunday newspapers now sell barely 6m between them. Some papers no longer make their circulation public, but Maher estimates that the Sun now sells about 770,000 against the Mail’s (audited) 780,000. By the same reckoning, the Times, which was selling 800,000 when Blair won his landslide in 1997, is now at about 216,000, while the Telegraph has gone from just over 1m to 188,000. Maher is at pains to point out that these are guesses, but his editor, Dominic Ponsford, says: “Nobody has complained yet”. If the figures were way too low, there’d have been howls.

Newspaper circulations have been in decline for a long time, but the rate of collapse has been accelerating. When David Cameron won his first election in May 2010, the Sun was selling 3m copies daily, the Mail 2m. Press backing was important for Cameron. In the first days of his premiership, he had meetings with Murdoch and Dacre, and by the end of July he had held “general discussions” with Tony Gallagher, then Telegraph editor, and his bosses, Aidan Barclay and Murdoch MacLennan. He met Geordie Greig, then editing the Evening Standard, Dominic Mohan of the Sun (twice) and Colin Myler of the News of the World.

He had also been interviewed by James Harding of the Times, spoken at the paper’s CEO summit, attended the Sun’s police bravery awards, and partied with the FT and the Spectator. Information released by the Cabinet Office lists more than 70 encounters and senior media executives in his first 14 months in office, including six with his Chipping Norton-set friend Rebekah Brooks, three of which took place at Chequers.

The hospitality was reciprocated. Cameron and his wife, Samantha, were among the guests at Murdoch’s summer parties at the Orangery in Kensington Gardens in both 2010 and 2011. Within days of moving into Downing Street, Cameron had appointed Andy Coulson, a former editor of the News of the World, as his director of communications. But Coulson (Brooks’s former deputy – and lover) had previously resigned as the phone-hacking coverage refused to go away. Three weeks after the 2011 party, the Guardian published its Milly Dowler story. By the end of the week, the News of the World had been shut down.

The Sun, Mail, Telegraph and Express embraced George Osborne’s austerity and ridiculed Ed Miliband. The result was an outright Tory win in 2015 that removed the shackles of the Lib Dem coalition partners and opened the way to the EU referendum they craved.

This, the Mail declared, was its readers’ victory. It then proceeded to beat the migration drum and mock Cameron’s negotiations with Brussels, dumping on him to such a degree that he sought to get Dacre sacked. Osborne the economic hero – “George’s epic strut” said the Sun in March, “Fearless George slays the dragons” said the Mail, in July – was transformed into a Remainer villain and ultimately, after the Cameron resignation honours, a “Companion of Dishonour”.

With the referendum won and Cameron out, the Mail took Theresa May under its wing. Dacre was the only media figure she met in her first six months – hosting a private dinner for him in October and appointing his political editor, James Slack, as her spokesman. When, a few weeks later, the paper demanded tougher penalties for drivers using their mobiles, she paused on her trip to meet the newly elected Trump, to announce just that. The following year, while juggling Brexit with ministerial scandals, she made time to join the celebrations of Dacre’s quarter-century of editing the Mail.

The Mail stuck with May to the end, and was almost messianic in its defence of Johnson, to the extent of indulging him with space to witter about cheese and chorizo at the expense of several proper journalists. It hectored the Tory Party into electing Truss and perpetuated the fantasy of her competence.

And so we moved on to Rishi – the traitor who brought down Boris. He was the man Truss had to beat. Now he’s in No 10. The Mail will, of course, tell voters to back him next year – probably by doing all in its power to discredit Starmer rather than by championing Sunak. If he wins, it will boss him for the next five years. If he loses, it will say he was the wrong choice all along.

Sunak appears no less eager than his predecessors to rub shoulders with the press. Johnson met Murdoch six times during his brief spell in Downing Street; Sunak has already notched up two such meetings. He turned out for Sun and Spectator awards evenings, and last December met Mail editor Ted Verity along with ITV news director Michael Jermey and BBC chiefs Tim Davie and Deborah Turness.

The next day it was the turn of Chris Evans, editor of the Telegraph, along with his deputy. Then later in the month it was Murdoch day with the big man himself, Robert Thomson, the former Times editor who is now News Corp CEO, and senior editors. These meetings are officially described as having taken place “to discuss the PM’s priorities”.

It seems that no PM can take office without making early contact with News Corp, the Mail or the Telegraph. Tory leaders rarely bother to mix with representatives of the Mirror, Guardian, Independent, i, FT or even the Express. The Murdoch papers, the Mail and, to a lesser extent, the Telegraph, are the ones they want to please. To be fair, why bother with the Express if it’s going to publish everything you say as gospel and without question, whereas it’s hard to escape the impression that the meetings with the big hitters are more about taking orders – cut taxes, emasculate the BBC – than sharing thoughts.

Aside from the obvious democratic concerns, is this a feasible strategy? Kelvin MacKenzie bragged that “It was the Sun wot won it” after Major’s surprise victory in 1992 (and, according to Murdoch at Leveson, was given an “almighty bollocking” for his trouble); Gallagher, then at the Sun, texted the Guardian after the referendum to gloat “so much for the waning power of the print media”. But does the press still have as much influence as editors and politicians seem to think?

Look at those circulations. People get their news elsewhere, most notably on social media, but also from publications that are increasingly seen as more reliable sources. Private Eye’s sales are growing as fast as newspapers’ are sinking. It sells around a quarter of a million copies a fortnight – that’s more than the Telegraph, Times, Express, Star, FT, i or Guardian can manage on an average day, and only a little behind the Mirror. Others, such as the New European and Byline Times, are also beginning to push through.

The Eye is known for its satire, but it breaks important stories and exposes corruption, whether on page 3 or in the sober section “In the back”. Yet Fleet Street is slow to follow up. And when it finally does – such as with the Horizon Post Office scandal – it claims all the credit.

Because it gets all the oxygen of publicity, it gets to choose the agenda. Its wares are on display in supermarkets and promoted in press reviews on radio and television that never look beyond the mainstream (and of course Murdoch has a radio and TV station as well as his papers).

The symbiotic relationship between the Tories and the right wing press will face its biggest test in the coming year. Both of their futures depend on it. If they fail, the party could face oblivion, the proprietors could lose billions. If they prevail, you can bet the BBC will be destroyed.

Starmer is the man who can write the script for these endings. He can expect no help, and a lot of hindrance, from the Mail and Murdoch. He may judge that if he keeps smiling through their abuse and misinformation, they might not give him the same treatment as his immediate predecessors – and he is claiming a post-party win in the shape of a Times front-page story about his new education policy.

Starmer may be vindicated. But he still should not have gone to Murdoch’s bash.

Liz Gerard is a former night editor of the Times and author of TRUSSED UP: How the Daily Mail Tied Itself in Knots Over the Tory Leadership