Remember the days when political scandals all centred on sex? We should be careful not to over-nostalgise these things – coverage at the time rarely thought about the power imbalances involved, nor that lots of them were rooted in homophobia and the need for ministers to live in the closet.

But despite all that, it still feels like a simpler time: minister who preaches morality cannot keep it in his pants. Whereas increasingly in 2023 it feels as if we’re ruled less by individual ministers and more that we have government by some sexless-yet-orgiastic blob, held together by a web of self-interest, grift and undisclosed “favours”.

No one except a criminal court can determine what does qualify officially or otherwise as outright corruption – as it should be – but the real issue is that there’s an increasingly toxic miasma surrounding the government.

What happens in countries where corruption is endemic is that institutions that are supposed to hold one another to account are made to blur into indistinguishability by way of reciprocal favours – whether that’s a well-paying government job for an ally (or crony), an agreement to look the other way, not to launch an investigation, or even to cause trouble for political rivals.

People quickly learn that how things really work and how things are supposed to work are unrelated – the rules as written down look scrupulous, and everyone makes a show of following them, but anyone near the top knows what’s really going on. The instruments of the state follow the rituals of independence, but the meaning behind it has gone entirely. All that’s left is reciprocity.

Conservatives would surely argue that their current wave of political scandals are completely different from the workings of states collapsing under the weight of corruption. But they are risking exactly that corrosive effect on the institutions of the British state – just this last week of scandals alone draws in the government, private enterprise, the civil service and the BBC.

Even trying to spell out the scandals would give Mary Poppins – of supercalifragilisticexpialidocious fame – reason to pause, but at this point it is impossible to track just quite how much is going on at once, and how it all inter-relates, without at least making the attempt.

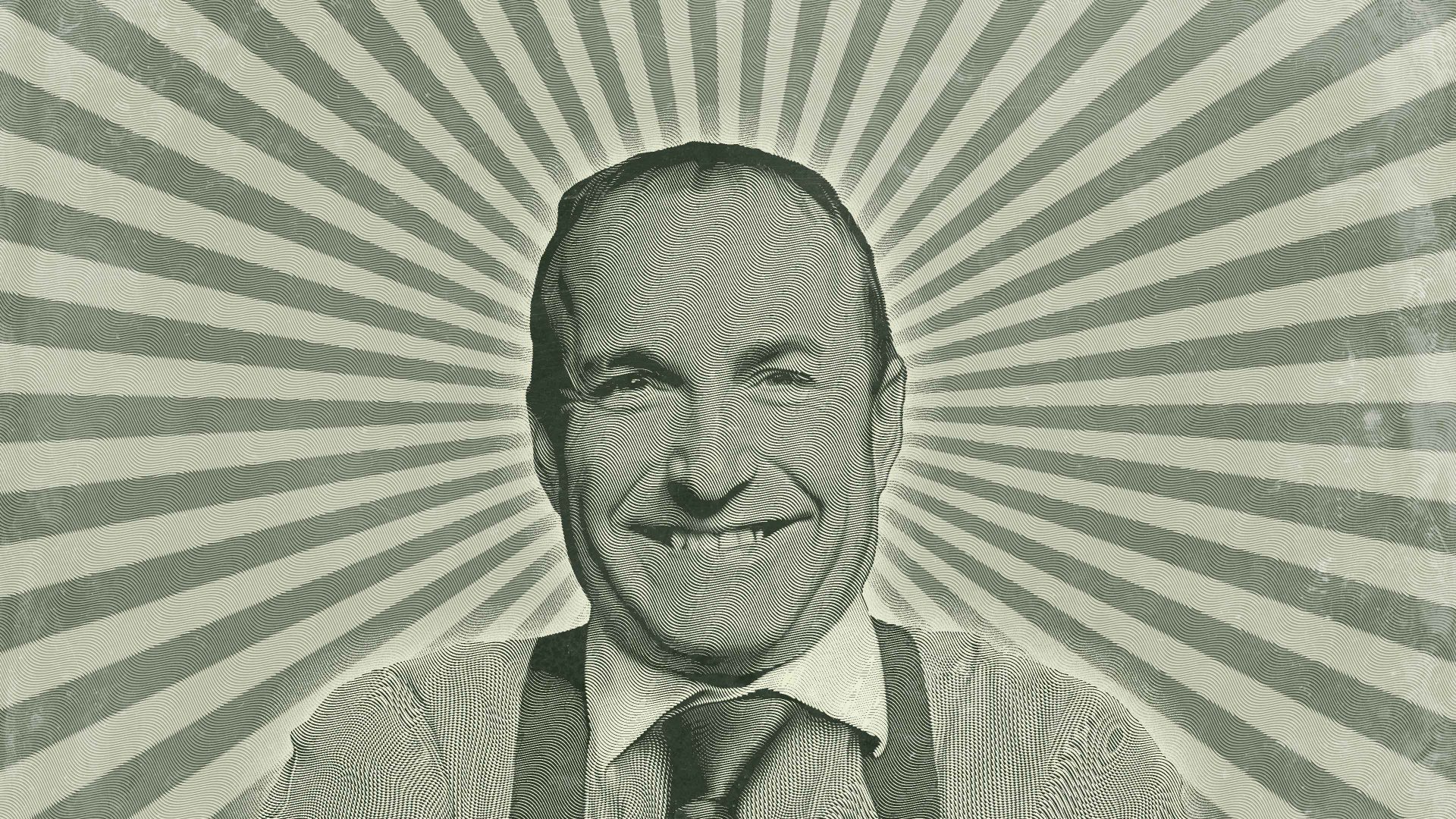

Former chancellor Nadhim Zahawi – who at the time of writing, but surely not by the time you read this, is still Conservative Party chairman – has been forced to admit he has paid, belatedly, a believed £5m to HMRC.

The money, which included a substantial 30% penalty for “carelessness”, related to a trust that owned a substantial shareholding in YouGov, of which Zahawi was a founder. Zahawi had offered a series of contradictory explanations as to what the trust was, why it was set up, and who its beneficiaries were, over several years of questions from the media.

This settlement appears to suggest that the trust did, in fact, operate as a holding body for Zahawi’s founder shares in YouGov – something Zahawi had intimidated several publications (and independent writers) into not publishing on multiple previous occasions.

As if all of that weren’t enough, it emerges that Zahawi was appointed chancellor – a role with ultimate ministerial responsibility over HMRC – while this dispute was still ongoing. And just to provide some cherry for the cake – and to remind us all of the Rebekah Vardy farrago – it has been reported this week that Zahawi exchanged text messages with former prime minister David Cameron during the Greensill lobbying scandal period. Zahawi had previously denied that this had taken place, but by the time it was confirmed it had, he sadly had somehow lost the messages concerned. Carelessness strikes again!

Former prime minister Boris Johnson, meanwhile, still faces full parliamentary scrutiny over whether he misled the House over the various #partygate scandals – something that on its own could scupper his endlessly mooted (by him and his supporters) return to frontline politics.

Sadly for Johnson, it is very much not on its own. As if it weren’t enough that it has now been reported that while as prime minister Johnson received an undisclosed loan of £800,000 that was aided by the presence of a distant relative as guarantor, said relative then applied (unsuccessfully) to be the head of the British Council.

Still, the whole process had been signed off by the cabinet secretary, Simon Case, who as ever displayed all the intellectual and moral brilliance of Baldrick on a bad day, seeing no issue with the whole shebang being kept private. As if all of that wasn’t enough, the process seemed to be set up and facilitated by BBC chairman Richard Sharp, a Conservative donor who received that role during the Johnson premiership.

In a twist of which surely only the BBC could be capable, the person responding to that breaking story on the BBC Sunday politics shows was none other than… LBC host Rachel Johnson, who is (as she hates to be reminded) not only the sister of the former PM, but also a good friend of Sharp’s. What a small world we are living in.

As various senior colleagues and former colleagues struggle, at least there is the deputy prime minister and justice secretary, Dominic Raab – except he is still under investigation for eight separate allegations of bullying. Despite the long and noble track record of internal scrutiny (especially while Case is in charge of the civil service), this one is fully independent, being overseen by Adam Tolley KC.

While this list is exhausting, it’s anything but exhaustive – there are ongoing investigations of various sorts into seemingly endless other matters, not least the Conservative peer Michelle Mone and her husband, around both PPE procurement and the possibility of the use of complex tax-avoidance schemes.

But of course, overseeing all of this is the prime minister, Rishi Sunak, who launched his prime ministership all those months ago – OK, three months ago – with a promise to end the constant parade of government scandals trailing out of Boris Johnson’s No 10 operation.

The number of scandals alone would suggest that Sunak is an exceptionally unlucky general, but that’s before we get anywhere close to looking at his particularly unfortunate entanglement with it all.

Like Zahawi, Sunak is also a former chancellor, and like his Conservative colleague he appeared to enter the Treasury with some undisclosed peculiarities for the person wanting to lead the UK’s economy. For one, in his first 18+ months in office, Sunak remained a US Green Card holder – a permanent residency status in the US, for which you have to agree that you have the intent to move there for life.

Sunak’s own family tax status was also revealed as complex during his chancellorship, when it was disclosed that his wife (who is a multimillionaire through family wealth) benefited from non-dom status.

So far, so unlucky – except when it comes to Johnson’s case, Sunak has headaches, too. For one, Sunak opted to keep Case as cabinet secretary despite his entanglement in multiple existing scandals, even at that stage. More problematic, though, is that Sharp, the newly appointed BBC chair, was not only a former colleague of Sunak’s at Goldman Sachs (where they did some work together), but Sharp also served as an adviser while Sunak was at the Treasury.

Raab, meanwhile, was at least deputy prime minister under Johnson, so that wasn’t a role to which he was first appointed by Sunak – except that Raab was stripped of that title by Liz Truss, only to have it reinstated when Sunak moved into No 10, leading to the resurrection of his scandals (and the subsequent announcement of an investigation) in the very first weeks of Sunak’s premiership.

And lest Sunak try to claim he’s got nothing to do with scandals around Mone and PPE procurement more generally, he will, alas, have to take that up with whoever was chancellor during the first two years of Covid. He will, at least, have no difficulty locating said person.

Sunak’s premiership hasn’t imploded quite as spectacularly as that of Truss. It’s far from clear whether that would even be possible. But just because it hasn’t failed spectacularly doesn’t mean it hasn’t already failed.

Sunak has done nothing to set out any kind of positive agenda, and he has only righted government finances by accepting a future of high taxes with public service cuts. He’s done nothing to show he has any grasp of the crisis that has hit the NHS, a service that was already on its knees. His bid to look strong in the face of the unions has made him look both weak and deluded, an addled King Canute sitting helplessly in front of waves he actually could have done something about.

But his most spectacular failure is in the easiest task that was in front of him: Sunak pledged to run a government with more integrity than that of Johnson, and now not only has he presided over a cabinet mired in scandal, but he has kept up his predecessor’s ability to drag other institutions of state into it.

Perhaps more surprising still is that he has continued Johnson’s gift of having some kind of personal attachment, connection, or resonance with virtually every political scandal occurring across his government.

Sunak increasingly looks like a man unmoored – he is running a government with no relation to his personal politics, he has no grip on the UK’s levers of power, and with his regular private jet use, he’s increasingly unmoored from the ground itself.

No wonder, then, that he’s the latest of our PMs to turn to a life of crime – with two fixed penalty notices in less than a year. Should the PM get an Asbo?