This week is a significant one for Rishi Sunak. Not just because of local elections, and not just because, as a cruel Westminster wit had it on Monday, Humza Yousaf’s departure means Sunak can no longer comfort himself that he is only the UK’s second-worst senior politician.

What has gone almost unnoticed is the matter of his tenuous mandate as prime minister. Already shaky, it is, from now until an election finally takes place, now even more so.

In constitutional terms, whoever can command a majority in the House of Commons has the right to serve as prime minister until the last possible date for calling a general election (more on this later).

Sunak might be dealing with a majority that has been considerably whittled down from the 80 Boris Johnson achieved at the 2019 general election, but on this front at least he is solid-ish, unless and until his backbenchers decide to mount another coup.

His moral authority to run the country has always had far less foundation. Johnson was elected in 2019 on a promise to get Brexit done and to boost funding for public services. Once Johnson was ousted, after what felt like an endless series of scandals around his fundamental lack of honesty, the Conservative Party held a leadership contest.

The winner of that leadership contest was, of course, Liz Truss – who had secured her personal mandate promising something very different: unleashing the potential of the UK for innovation and growth through deregulation, shrinking the state, and cutting taxes.

This always polls horribly, but the interaction of Tory rules with the UK’s constitutional conventions put the party’s relatively tiny membership base in charge of picking the next resident of No 10 – and Truss felt no need to be bound by the manifesto that gave rise to her majority.

Once she went too far, too fast in about as stupid a way as possible – one wonders how short her premiership would have been had it not been mostly filled with a period of official mourning – Conservative MPs were reluctant to trust their party members with another big decision.

Through that process, Sunak was grudgingly accepted as the first-among-losers, given the need for almost anyone who could calm the markets’ panic. He’s had little chance to choose a proactive agenda, but his big decision is to cut taxes – so far with two cuts to national insurance.

That comes at a time when support for better-funded public services is huge, and where much of the public sector is visibly falling apart despite the best efforts of those working in it. Sunak is using the dregs of Johnson’s term to push through a policy agenda that bears no resemblance to the one voters opted for.

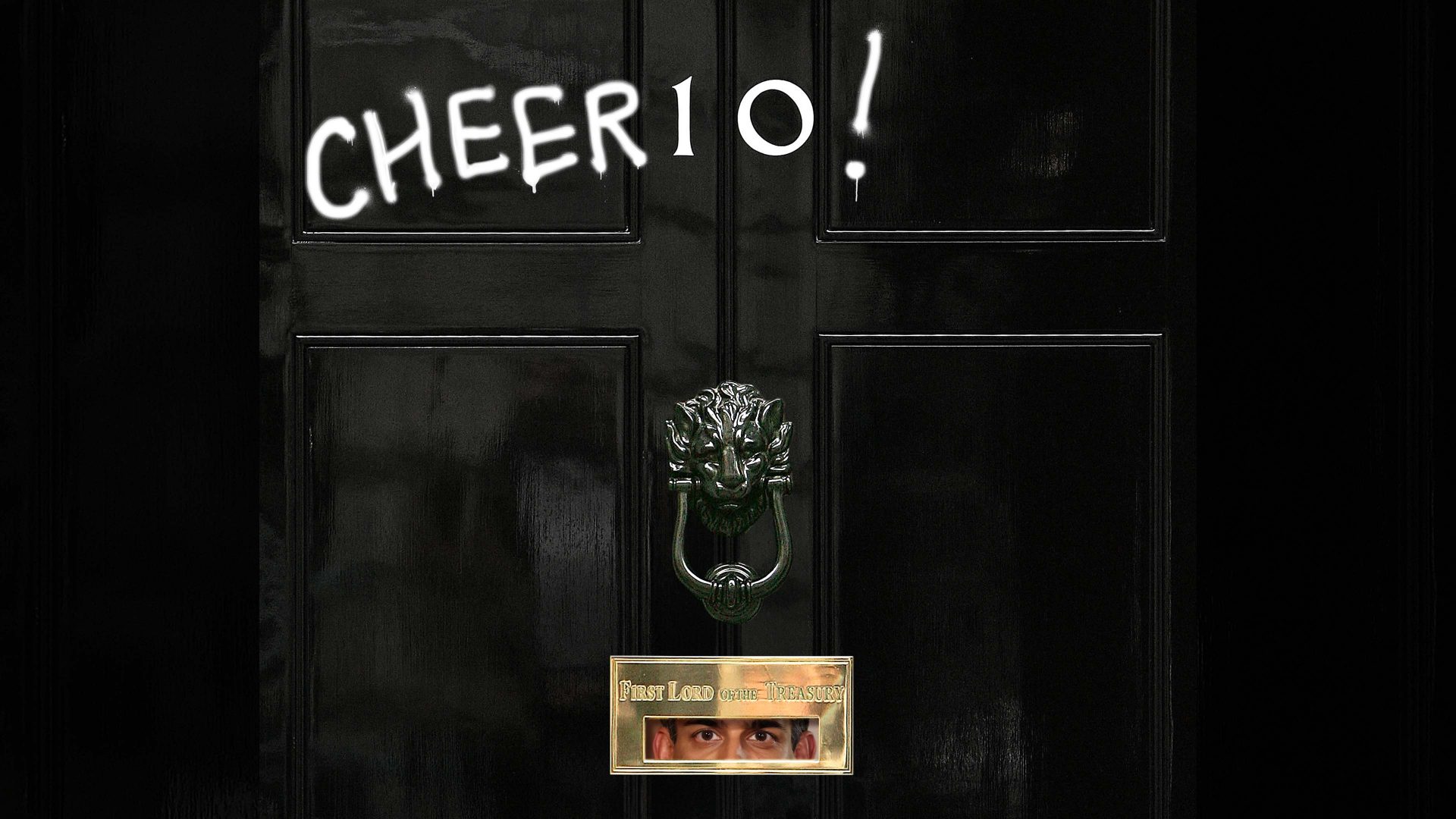

All of that is essentially prologue – it has been the status quo since Sunak was bundled into No 10. What has changed this week is something that hasn’t happened in modern British politics: this government is staying in office after what should have been the last day of its term.

When the 2019 general election took place, the UK still had the Fixed-term Parliaments Act in place. This 2011 Act governed the length of parliamentary terms and what happened in the case of snap elections. The rule at the time of the last election was that if a snap election (like 2019’s) was held, the next “proper” general election would take place on the first Thursday in May – which would be, you guessed it, May 2, 2024. At the time this government was formed, that was the last possible day for a general election.

If you’re wondering why Sunak hasn’t called an election for that date, he is not simply ignoring the law. When Johnson was still PM, the government repealed the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, which was in reality a tactical law to help solidify the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition of 2010-2015, masquerading as constitutional reform.

It is the way in which the Conservatives repealed the act that allows Sunak to cling on to his premiership. The repeal reinstated the previous rules governing parliamentary terms and general elections, which required a general election no later than five years after the date of the last one – and without fixed terms, there is no difference between a “snap” election and a scheduled one.

That little-noticed change allowed the Conservatives to extend the maximum term of their time in power by almost eight months – something that is absolutely without precedent in modern British politics. Someone wanting to do huge Twitter numbers could (and might) present this as a constitutional outrage – it certainly feels odd that a government voted in with a use-by date of this week could choose to extend its own term.

In reality, the outrage should be at least somewhat muted by the fact that the 2019 Conservative manifesto did include a pledge to repeal the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, even if it didn’t explicitly note that this would extend the potential life of the government.

Fixed terms don’t really make sense in parliamentary systems – if a leader’s right to govern is based on parliamentary maths, which is notoriously changeable, mechanisms that ignore that reality are doomed to fail. Fixed terms make sense in presidential systems, but are generally only convenient fictions in systems like ours.

The government was probably, then, right to repeal the act – but it has done so in a characteristically self-serving way. This could easily have been avoided, with one small clause noting that the last day of this parliamentary term would remain unchanged – but, funnily enough, the government decided not to do that.

From this point on, then, any day of Sunak’s premiership is on time that is at best borrowed and at worst stolen – days beyond the mandate offered by voters in 2019. Sunak’s moral authority to make big changes was already tenuous – it is now gossamer thin.

Just how much further is he prepared to stretch it?