In a nation that feels increasingly like the George Bailey-less Pottersville from It’s a Wonderful Life governed by oafs, liars, smirking dimwits and rapacious racketeers, I can actually bring some good news. I know! I can barely believe it myself. Brace yourself, here goes.

The UK publishing industry is in rude health. Arguably its health has never been ruder.

Last week saw the release of the Publishers’ Association’s annual breakdown of UK book sales, and the figures make, if you will, excellent reading. The UK industry raked in £6.7bn in 2021, a rise of 5% on already healthy 2020 levels. While £3.8bn of that is from export sales, considering these two years were swamped by the pandemic and bookshops were closed altogether for a significant period, £2.7bn in home sales represents a frankly startling state of affairs.

Non-fiction led the way in the consumer sector, generating £1.1bn, while fiction pulled in £733m, not all of which was earned by books written by Richard Osman (although two of the four bestselling titles were by him).

These figures would have been enough to trigger whooping and high-fiving across the industry if Covid had never happened. To achieve such buoyancy in the most constricting circumstances since, well, probably since the Black Death, is almost unbelievable.

It’s just reward in particular for booksellers who, faced with the retail rug being pulled from under them with the imposition of lockdowns, worked incredibly hard with great imagination to keep their customers supplied with books, from beefing up websites to offering free local delivery, sometimes by bicycle.

The fastest area of growth, with sales up 14% on 2020, was audiobooks, a genre that had been expected to take a battering given hardly anyone was

commuting or travelling long distances during the pandemic.

Perhaps the biggest talking point, however, is in the makeup of the books sold in the UK last year.

The healthy sales in 2020 were inevitably dominated by high-profile, newly published titles. They were gaining the column inches of review sections and enjoyed publicity campaigns that pointed people towards online retailers via online events. With no shops to wander around in, people were buying the books they saw on their screens and those books were almost exclusively new ones. Backlist books, those not still enjoying the heady whiff of freshly printed paper and freshly minted publicity drives, suffered because with shops closed people had no way to browse. Two thirds of the books sold in person in shops are classed as unplanned purchases, books people haven’t gone into the shop looking for specifically but spot on the shelf, or on a promotion table near the entrance, or on the always popular “staff picks” shelves where booksellers write cards explaining why they enjoyed this particular title.

You can’t write an algorithm for that kind of browsing serendipity, so sales

from the backlist took a heavy hit in 2020 and weren’t expected to do hugely

better last year, even allowing for shops being open for a longer period. Yet these books performed far better than expected, with some backlist titles finding themselves nudging into bestseller lists despite having been published anything up to a decade ago.

The reason for this renewed interest in titles that nestled far from the front

tables and review pages? You might be surprised to learn that it’s TikTok.

Since its international launch less than five years ago, the social media platform on which users upload short videos has gained more than a billion

active users, a figure even more remarkable considering it’s not available in either China or India. TikTok’s user-friendly editing tools and wide range of filters and rights-free music make it simple for subscribers to exploit their creativity, notably in the posting of things like dance routines and comedy sketches. Its fast pace and popularity with a younger demographic than other social media apps doesn’t make it an obvious source of successful book

promotion, but the BookTok subcommunity has proved to be a powerful phenomenon that nobody saw coming.

As the name implies, BookTok is a tag in which creators post short videos

about books they’ve enjoyed accompanied by easy-to-use graphics and soundtracks. Some are barely six seconds long, none are more than a minute. It sounds niche and superficial, but since it first emerged less than two years ago BookTok has gained more than 50bn views. It’s difficult to convey how staggering that figure is, but try thinking of it as the equivalent of every man, woman and child on this entire planet watching six BookToks each.

Having developed entirely organically, the BookTok phenomenon is not driven by the publishing industry, meaning the books featured are rarely new titles and come from a range of genres. These are the books readers have pulled off a shelf at home or been given as a present and want to share how much they love them online. A TikTok video is quick and easy to make and demands nothing more from the viewer than a few seconds of their time.

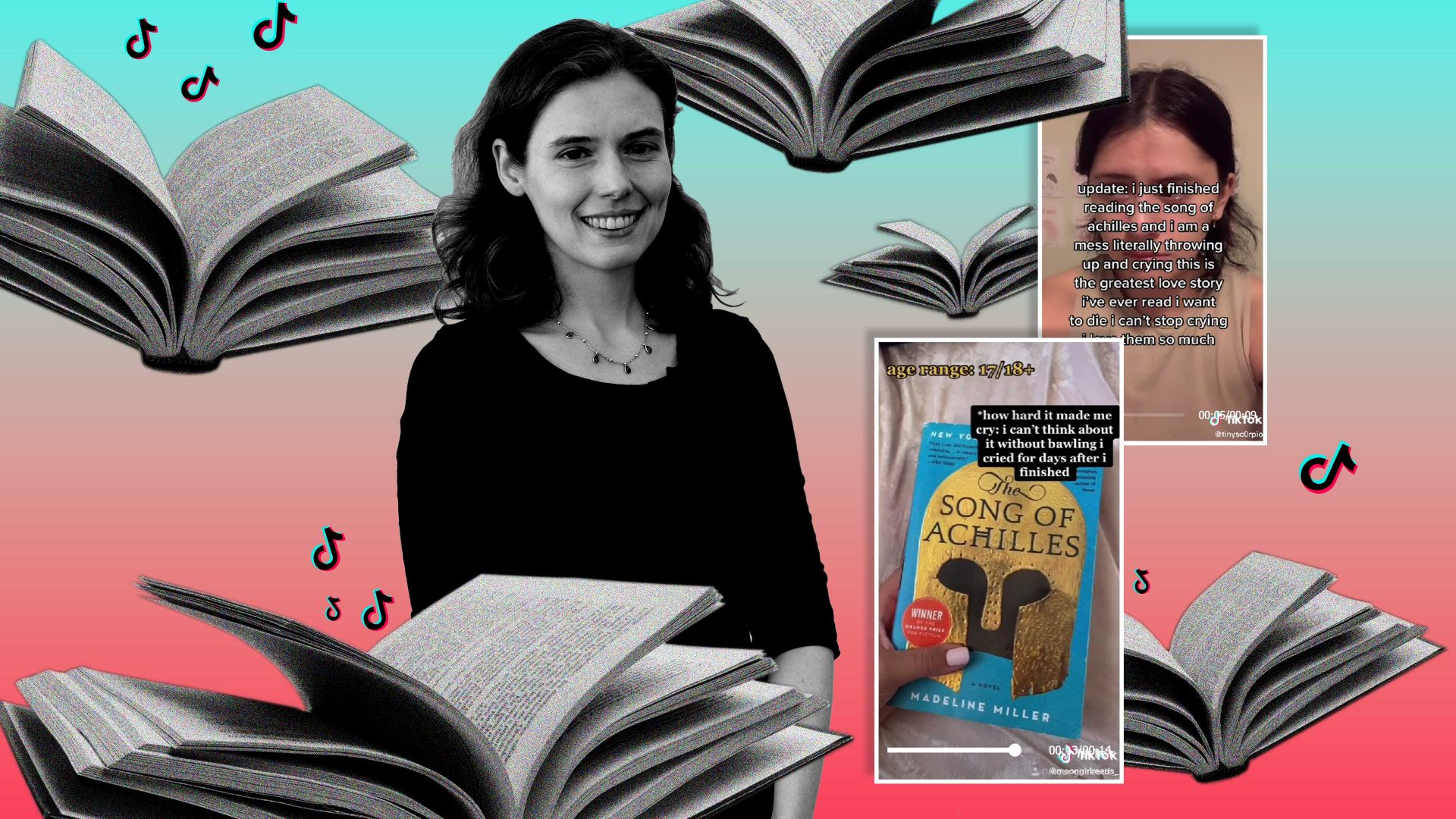

The knock-on effect has been remarkable. Take the 27-second video made in August 2020 by BookToker @moongirlreads_, aka 18-year-old Californian Selene Velez, when she was asked by one of her 223,000 followers to list books that had made her cry. One of the four titles she cited was The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller.

“I can’t think about it without bawling,” Velez posted, “I cried for days after I finished it.”

The video soon gained more than six million views and in April last year, eight months after Velez published her BookTok, Miller’s decade-old reimagining of The Iliad reached number one in the New York Times bestseller chart. In Britain, Miller’s publisher, Bloomsbury, reported profit growth of 220% in its interim results for the first half of 2021, a considerable chunk of which was down to the surge in demand for Miller’s debut.

Perhaps the strangest example of BookTok’s influence was the case of Cain’s Jawbone, a 1934 whodunnit by crossword compiler Edward Powys Mathers consisting of 100 loose pages that would only reveal the killer if assembled in exactly the right order. Fiendishly difficult, the book was briefly popular before the war (and solved by only two people, who won cash prizes) then vanished into obscurity until it was revived with a small reprint by the crowdfunding imprint Unbound. Last autumn BookToker Sarah Scannell got hold of a copy and began charting her progress in solving the puzzle. Orders

for the reprint immediately went through the roof, 10,000 coming from the US alone, turning Cain’s Jawbone into one of the unlikeliest bestsellers of the current millennium.

Inevitably the publishing industry, having had this bonanza tumble unexpectedly into its lap, is muscling in on the action. The US bookshop chain Barnes & Noble created a dedicated BookTok section on its website, while leading BookTokers are sent advance copies of forthcoming titles by publishers and in some cases, creators are being offered payment for promotions. While that does feel a little like a deflating loss of innocence, it seems unlikely that BookTok will be overrun by publicists and corporations. The BookTok phenomenon should be large enough to remain dominated by the simple passion for good books rather than the short-term desires of the industry.

If anything, BookTok has resisted the new. Of the current 20 most popular BookTok titles only two were published in the last two years. Miller’s The Song of Achilles occupies the top spot on a list that also features Delia Owens’ 2018 bestseller Where the Crawdads Sing, Anthony Doerr’s 2015 Pulitzer-winning All The Light We Cannot See, The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde, first published in 1890, Hanya Yanahigara’s dense, 800-page A Little Life from 2015 and Jane Austen’s Persuasion, which dates all the way back to 1817. For a medium dominated by such a young demographic it’s interesting to note that while Young Adult fiction features in the list it is far from being the dominant genre.

BookTok is not perfect – it’s dominated by white women mostly talking about books by white women, the TikTok algorithm having received criticism for disproportionately favouring white faces – but even the briefest of delves into its world is a joyous experience. Watching people expressing their love of books with genuine emotion is rewarding enough, but tying that in to a 20% increase in UK fiction sales over a two-year period fraught with global anxiety and shuttered bookshops is the kind of wholesome, good news story we all need.

This is a social media phenomenon that even Elon Musk can’t stink up.