From 1945 until very recently, there was a law in force in Czechia which stated that surnames had to be inflected grammatically to indicate whether the bearer of the name was male or female.

This was mostly achieved through the surnames of women and girls taking an added suffix indicating feminine grammatical gender. The most common of these suffixes, as discussed in last week’s column, is -ová. This practice has been somewhat controversial among certain contemporary Czech people because -ová, even though very traditional, can be interpreted as signifying possession, in the sense that Dvoráková means “wife of Dvorák”. Similarly, for unmarried women, the suffix indicates “daughter of ”: the famous Czech tennis player Karolina Plíšková is the daughter of Radek Plíšek.

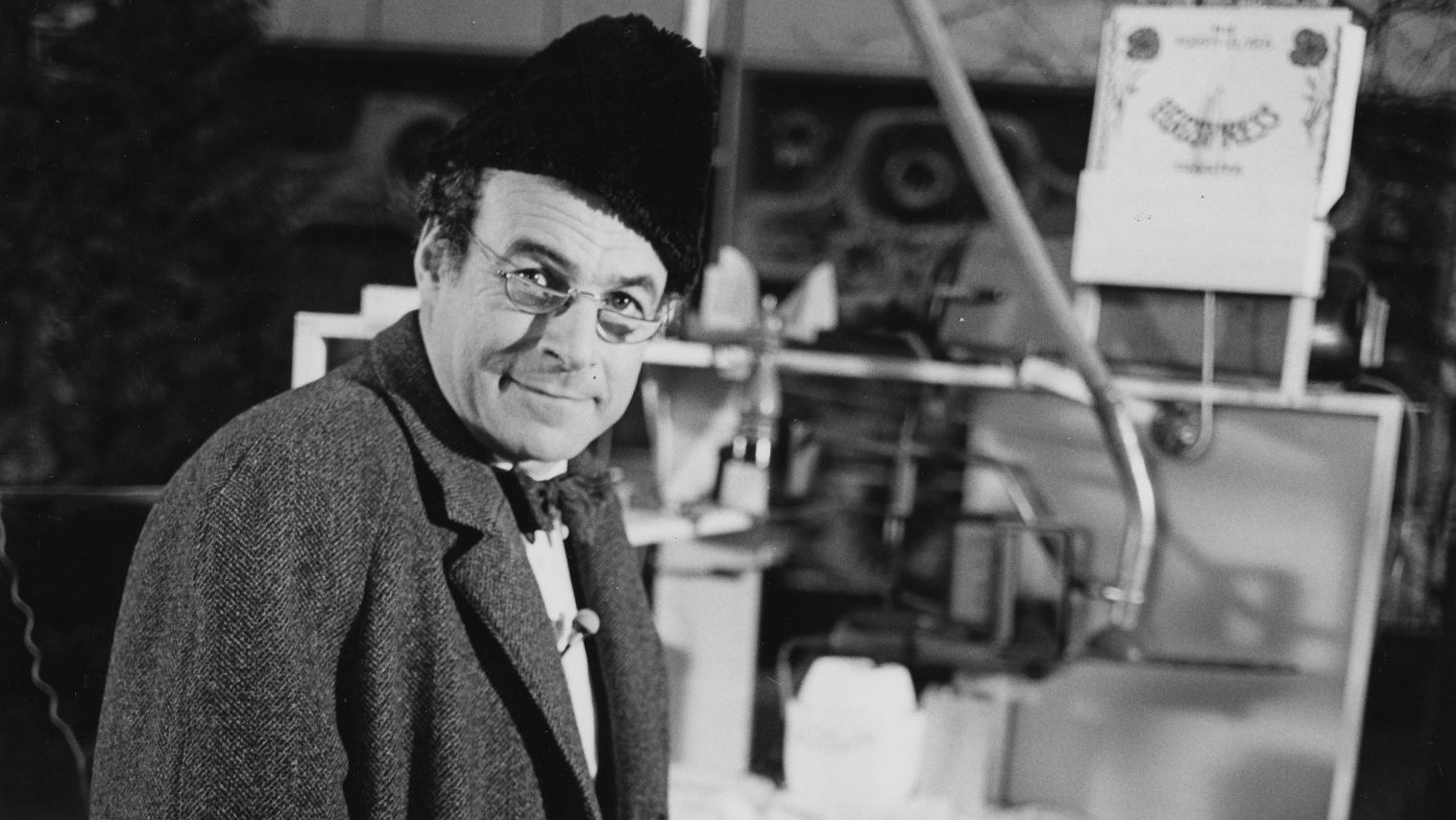

This Czech practice is so widespread that it is even applied to the names of prominent non-Czech women, such as politicians, scientists, and writers. Angela Merkel is known in Czech as Angela Merkelová. The Czech translation of Pride and Prejudice, which has the title Pýcha a predsudek, has an author called Jane Austenová (pictured). And the prime minister of New Zealand is referred to in the Czech press as Jacinda Ardernová.

Some family names that were originally adjectives do not take this -ová ending. The male surname Chromý, an old adjective originally meaning lame, has the feminine form Chromá. Out of the 23 members of the current Czech women’s football squad, 22 have names ending in -ová, but there is one exception, Franny Cerná, whose surname is equivalent to the English-language family name Black. Cerná, “black, brown, dark”, is the feminine form of the Czech adjective, which in the corresponding masculine form is cerny.

As reported earlier in TNE, the 1945 law has recently been rescinded by the Czech parliament, which pleases those who have come to feel that it is demeaning for women to have a compulsory linguistic marker on their names denoting what they see as possession, but it has not been welcomed by traditionalists.

It is significant that that law originally came into force in 1945, which was, of course, not just any old year. One possibility is that the legislation was passed then because it was at precisely that time, at the end of WWII and after the horrors of the Nazi occupation, when perhaps as many as three million ethnic Germans were being expelled from Czechoslovakia.

Like English-language surnames, German-language surnames are genderless. It might well be that non-gendered Czech surnames sounded too Germanic at that sensitive period in history. And this, of course, was a time when Czech people were still recovering psychologically and culturally as well as politically and economically from the devastating effects of the war. So it may have been motivated by anti-German sentiment.

Also at that time, there were some ethnic Czechs who happened to have German-origin surnames, who changed their surnames to Czech forms. The Czech WWII hero Tomáš Lom, who died earlier this year aged 96 and was the last surviving Czech RAF airman, was originally called Löwenstein.

But plenty did not. The famous Czech tennis player Ivan Lendl has an originally German-language surname, as does the former Czech President Václav Klaus. The well-known film director Miloš Forman, who directed One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, also had a German name.

Devastate

It may not be immediately obvious that the English verb devastate (destroy) and the adjective vast (very large) might have something to do with each other.

But, in fact, they both go back to the Latin form vastus (void). So vast was originally “immense void” and devastate was originally “to lay waste”.