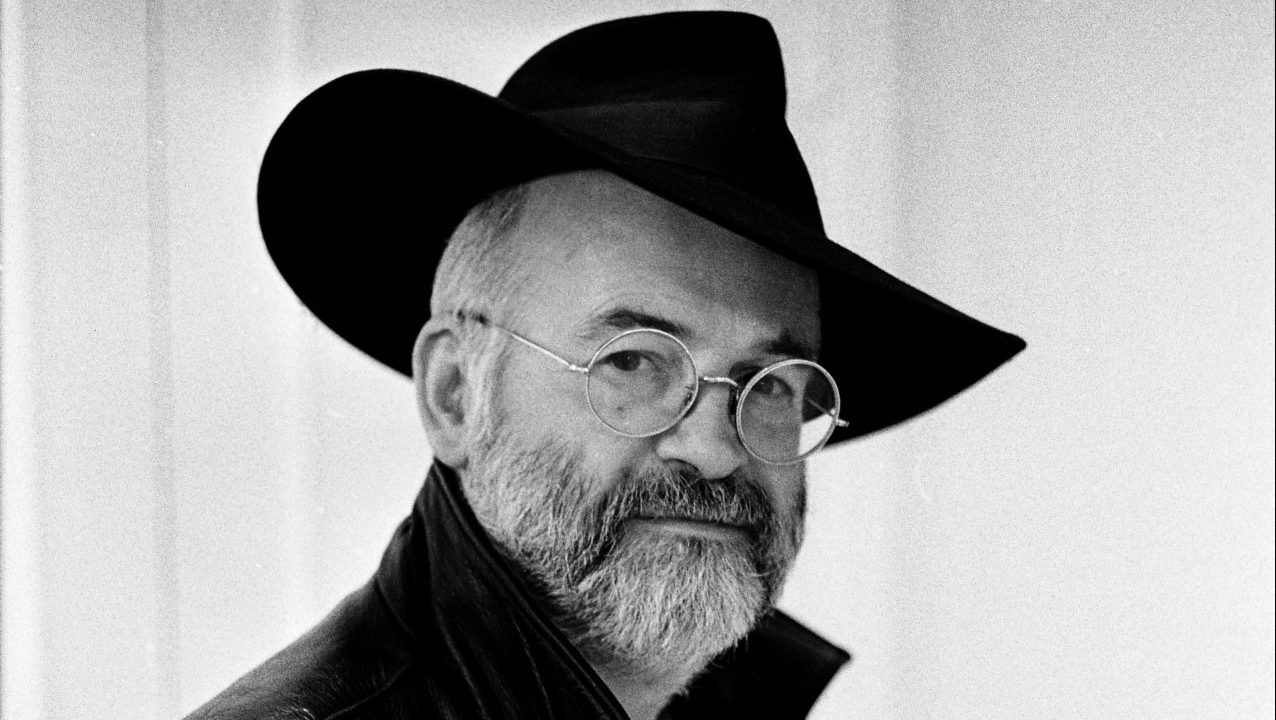

There was much rejoicing in Terry Pratchett world last week with news of the publication later this year of A Stroke of the Pen, a collection of recently rediscovered short stories that the Discworld creator, who died in 2015, wrote for a British regional newspaper during the 1970s and 1980s, most of them under the pseudonym Patrick Kearns.

The collection, subtitled The Lost Stories, will be published in October by Transworld, who are understood to have paid a six-figure sum to Pratchett’s estate to secure the 20 tales that re-emerged after almost half a century thanks to some tenacious sleuthing by fans.

Chris Lawrence had read one of the stories, The Quest for the Keys, in the newspaper as a 15-year-old and was so captivated he had it framed and displayed on his wall for more than 40 years before contacting Pratchett’s agent Colin Smythe to inform him of its existence. This prompted a search by two Pratchetteers, Pat and Jan Harkin, who combed through old newspapers to unearth the rest, which predate Pratchett’s bestselling Discworld series.

“For all the years I was Terry’s publisher and then agent he never ever gave me any help in finding his shorter writings,” Smythe told publishing trade journal The Bookseller, “but as he wrote in his dedication to me in Dragons at Crumbling Castle, there were stories he had carefully hidden away. Just how true these words were, I had no idea.”

Pratchett’s long-time assistant, Rob Wilkins, said: “The rediscovery of these stories is nothing short of a miracle and represents the last ‘new’ Pratchett material we are ever likely to find. While Terry was always very focused on the next novel and maintained that his unpublished works should never be released, he always held a grudging admiration for his younger self’s work and he would be tickled to see these stories celebrated in one wonderful volume”.

Now, exciting as the discovery of this trove of Pratchett undoubtedly is, I couldn’t help noticing something in those effusive quotes about the forthcoming collection.

For Smythe, Pratchett “never gave me any help in finding his shorter writings,” while Wilkins reminds us that the author “maintained that his unpublished works should never be released”.

So determined was Pratchett that his bibliography remain set in stone at his death that, according to Wilkins, he mooted “a device connected to his heartbeat so when his heart stopped it would wipe the contents of his hard drive”. As it was he left instructions for his computers and hard drives containing unpublished and unfinished writing to be crushed by a steamroller.

“There are ten titles that I know of,” Wilkins told the BBC, “and fragments from many other bits and pieces”, all of which were destroyed with some degree of ceremony under the wheels of a vintage steamroller called Lord Jericho at a Dorset steam fair in 2017.

The material contained in A Stroke of the Pen was not on one of those hard drives, nor were they discovered in an envelope at the back of a drawer or anything; they had appeared in print in newspapers during a period when Pratchett was already a published author. They are, by any standards, fair game. Pratchett’s estate, administered by his daughter Rhianna and fiercely protective of the author’s legacy, gave permission for the collection to be published and the widespread delight that greeted the news makes the book one of the most exciting publishing events of the year.

Hearing about A Stroke of the Pen and its provenance still made my blood run a little cold, however. I can’t help wondering whether the author really would have been “tickled” to learn that a bunch of stories he wrote under pseudonyms for a provincial newspaper decades ago were being released into the world with his name on the cover to a honking great fanfare.

I say this not through any insight into Terry Pratchett’s character, nor out of any disapproval of the book itself. The decision to publish came from those closest to him and would not have been taken lightly. No, my conniptions are rooted in a personal horror at the absolute bobbins I have lurking on some of my old hard drives and the abject humiliation I would feel if they were ever sent out into the world when I wasn’t looking.

Posthumous literary publication has always made me uncomfortable. Books I’ve written, finished, seen edited and published make me knuckle-gnawingly anxious enough, let alone half-baked stuff that I wouldn’t dream of showing anyone because it’s either unfinished or just rubbish.

Many successful writers will have THAT manuscript somewhere, hidden away in a distant corner at the end of a labyrinth of folders on their computer or as a sheaf of paper in a box under the bed, taunting them like a mischievous imp. More often than not this will be their first attempt at a novel on which they once worked obsessively, honing and crafting, revising and reworking, before either having it rejected by every publisher in the country or realising before it was too late that it just wasn’t any good.

The experience will have been invaluable, however, and that fledgling dud will have made subsequent work much better. However, the thought that after you’ve joined the holy choir invisible, some well-meaning literary executor might stumble across that sheaf of paper or wade through enough hard drive to not only locate that colossal turkey but have it published is a frankly terrifying one.

That’s not to say that posthumous discovery has always been a bad thing for literature. The famously reclusive Emily Dickinson published only a handful of poems during her lifetime but after her death in 1886, her sister Lavinia found hundreds of them among her papers. While Dickinson had left instructions that all her correspondence be destroyed, this request didn’t specifically include her poems, the first volume of which was published four years later.

When Franz Kafka died in 1924 he was barely a footnote in the world of literature and left instructions for the writer Max Brod to burn all his papers – including the manuscripts of The Trial and The Castle. Instead, Brod went on to edit, annotate and oversee publication of a literary legacy that turned Kafka into one of the greats.

This overruling of their dying wishes may have left Kafka and Dickinson spending their eternal rest clutching each other in a horrified embrace of wracked mortificiation, but hey, them’s the breaks.

Too often, however, when previously unpublished work by great authors is unearthed, the excitement of the discovery outpaces the quality of the material by some distance. In 2016, for example, an early short story by Sylvia Plath submitted to and rejected by Mademoiselle magazine in 1952 came up for auction and was published three years later as a 48-page paperback called Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom. An unspectacular coming-of-age story, the piece would have been entirely forgotten had its author not gone on to great things. The editors at Mademoiselle who sent it back probably got it right.

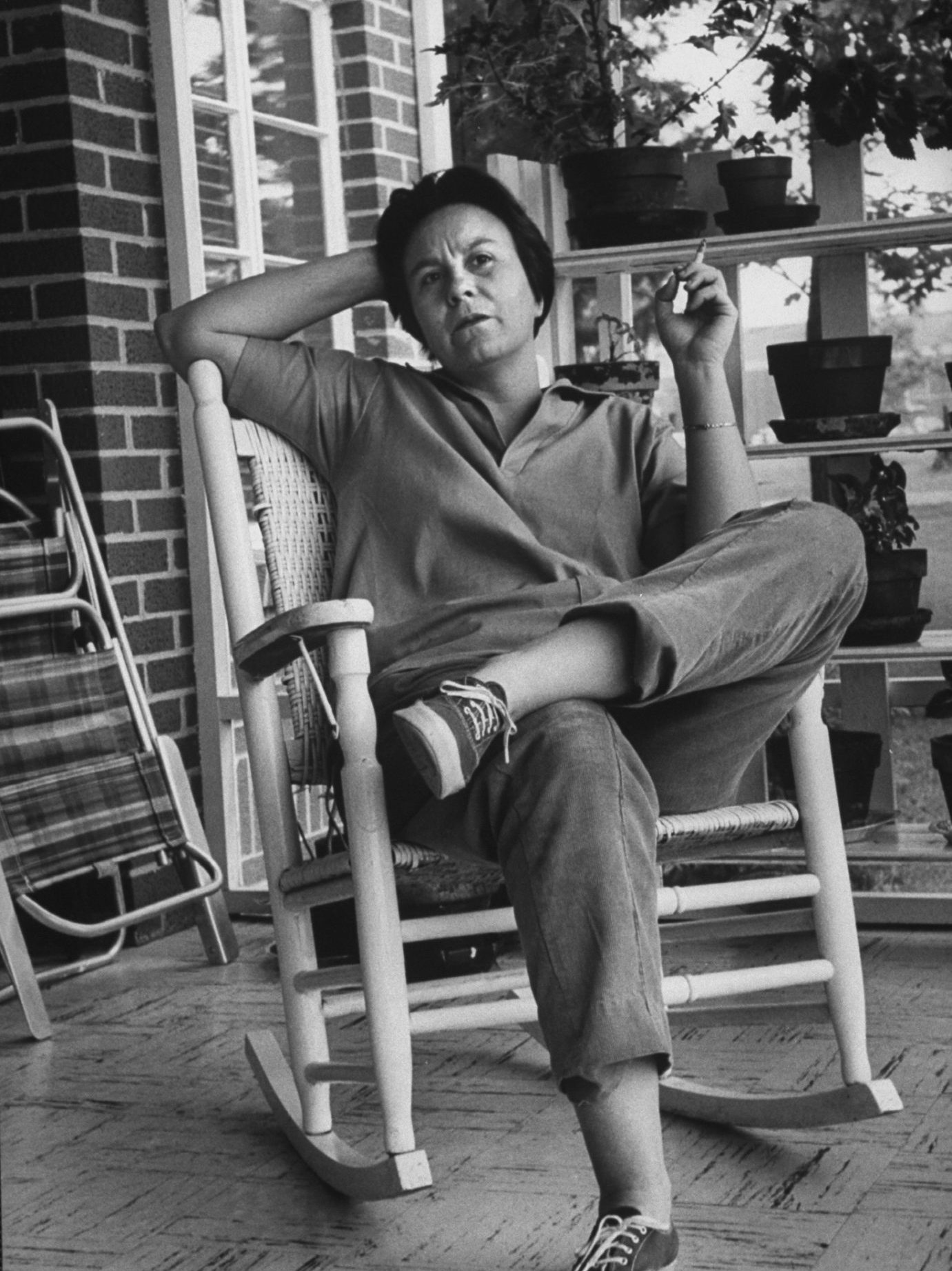

Perhaps the most notorious example was the 2015 publication of Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, written in the 1950s and effectively an early draft of her only published work To Kill a Mockingbird. The affairs of the famously reclusive and by then ailing 89-year-old author were being administered at the time by a lawyer who was the driving force behind publication; Lee herself having insisted over many decades that she would neither write nor publish another book.

“I have said what I wanted to say,” she insisted to a friend, “and I will not say it again.”

Go Set a Watchman was published amid accusations of coercion of its vulnerable, elderly author who died four months after publication and was clearly a novel by a writer yet to find her voice, an uneven work considered unpublishable when written but one in which an editor recognised something in Lee that would lead to the writing of Mockingbird. Reviews were lukewarm and, like Plath, Lee’s literary reputation was not enhanced one iota. In fact, the whole affair just felt a bit tawdry.

A finished, published book should be all music and magic, as good as it can possibly be. A work that’s only part of the way there or shows the author’s workings only tarnishes that magic. Ultimately, if a writer hasn’t submitted a book for publication there’s a good reason for it. A book belongs to an author until they are prepared to part with it.

Sometimes though, even in death, an author can definitively have the last word. When Blockheads frontman Ian Dury was diagnosed with cancer in 1996, he was persuaded to write his memoirs. Presented with a laptop on which to work, he was seen regularly tapping away at the keys deep in concentration. Whenever someone enquired how it was going they always received a cheerfully positive response and the prospect of reading Dury’s remarkable story in his own words induced thrilled anticipation among fans and publishers alike.

Dury died in 2000 and after the funeral, someone in his entourage remembered the laptop. The memoir! Had he finished his memoir? The device was powered up and the screen came to life. On the desktop was just one document, the only item on the entire machine. This was it. The posthumous memoirs of Ian Dury.

With a double click of the mouse, the document opened. And there it was. A single page containing, in giant letters that filled the screen, just two words.

“Hallo sausages!”

A EUROPEAN LIBRARY

76. FORGOTTEN LAND: JOURNEYS AMONG THE GHOSTS OF EAST PRUSSIA by Max Egremont (Picador, £14.99)

East Prussia has long vanished from the map but its legacy lingers. It has a rich history in literature, art and philosophy but suffered more than most during the violent machinations of the 19th and 20th centuries. This immersive, meditative, melancholic travelogue is a brilliant evocation of a key part of Europe that has been all but forgotten.