While it is still too early to say how well or otherwise the publishing industry in the UK fared in 2024 there is no reason to doubt that, financially at least, the sector is in pretty rude health. In 2023 UK publishing revenue topped £7bn for the first time, contributed £11bn in total to the economy and supported 84,000 jobs, all while continuing the small but steady year-on-year revenue increases we’ve seen since before the pandemic.

There is much to celebrate. It has never been easier to buy books, on the high street or via online outlets, while the discussion of books is also more accessible than ever.

From the extraordinary BookTok phenomenon to some outstanding literary podcasts to BBC2’s excellent Between the Covers series to the book groups that gather in the nation’s bookshops, living rooms, libraries and community centres, there is much chatter as well as much reading.

We should be wary of complacency, however, as UK publishing still faces many challenging issues, some out of its hands, others definitely not. While many can be measured in pounds and pence, others are a little more existential, making this a wish list rather than some kind of manifesto. But all are still crucial to the wellbeing and potential of the literary world we love.

So, what are the issues facing us as we wander into another reading year? The effects of Brexit, of course, continue to cause problems for readers, authors and publishers alike. As in every other industry, the staggering amount of bureaucracy involved in exporting and importing books and the raw materials to make them makes life harder for everyone. For authors and publishers the removal of EU copyright protection that made things easier when we were members of the European Union is yet another Brexit-related challenge.

Everything has become slower and more complex since leaving the EU, from tax and customs forms to even the logistical bureaucracy now involved with publishers simply attending the Frankfurt Book Fair, the most important annual event in the publishing calendar.

Brexit has also exacerbated the effects of the economic downturn, with the price of everything from paper to warehousing rising significantly and staff recruitment becoming harder.

Outside this publication, Brexit seems to have become the Great Unmentionable despite its destructive influence having seeped into almost every aspect of our lives. Even bringing up its continuing effects on the world of books feels like the reheating of old arguments, but those arguments were won long ago yet here we are, everyone still suffering, including readers, authors and publishers.

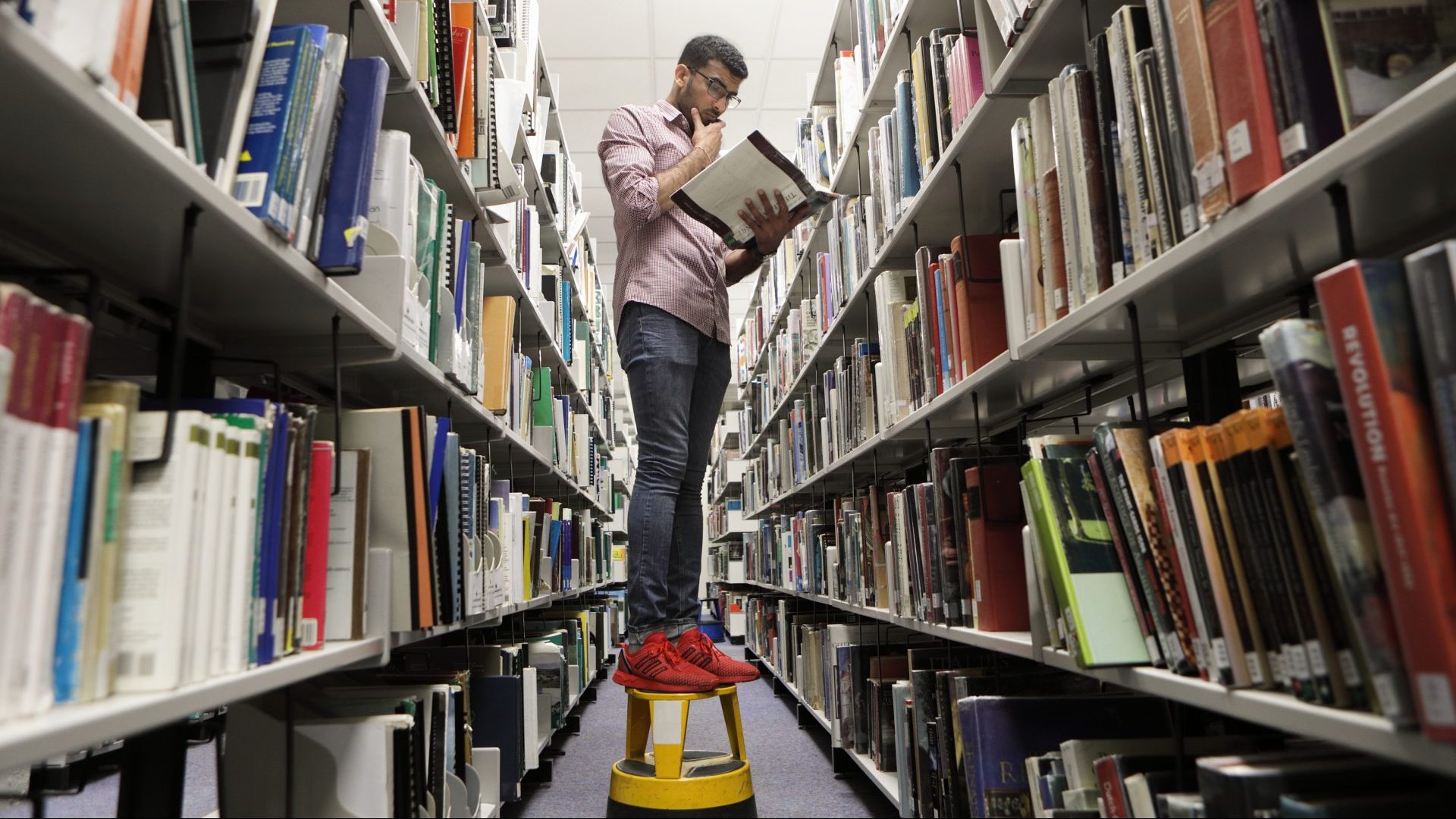

Away from the B-word, most people agree that the importance of libraries cannot be overstated yet this already battered public service faces more challenges with each passing year. The very existence of public libraries is of course baffling to those of a right-wing persuasion, given they provide their services free to the user and cannot turn a direct financial profit.

Yet libraries have an incalculable value to the nation’s cultural and economic wellbeing that free-marketeers will neither admit nor appreciate. The victory of the library is in its fostering of autodidacticism, training for employment and just basic reading for reading’s sake.

From starting a new business to researching local history to researching a new career to choosing your basic, good-old bedtime read, the library has you covered almost every way you turn.

The modern library has become a wider community hub than simply a place to borrow books. The library today is a place where people can seek advice in a range of areas, access the internet for free or even just come in and warm up on a cold day.

The core role of the library should always be free access to books, aiding self-improvement, mental wellbeing and just getting stuck in to a cracking read for the sake of it, but the evolution of the dusty old library into something modern and more widely useful despite the horrendous cuts and closures has been heartening to witness among the carnage.

The library is an extraordinary resource whose benefits outstrip cost by a considerable distance. Bean counters may shake their heads in bafflement but a public library represents one of the most vital and beneficial investments available to the people of this country today.

Readers and authors alike benefit from the library, the former able to sample and enjoy writers they might not otherwise have the opportunity or be able to afford to read, the latter receiving a small financial recompense every time their books are borrowed thanks to the Public Lending Right.

Defending our libraries and even increasing investment in them is vital to the wellbeing of us as individuals, the knock-on effects of that benefiting the nation when, in these post-Brexit, post-14 disastrous years under the Tories times, it needs it most.

Access to books goes beyond the physical act of walking into a library and browsing the shelves, however. What’s on those shelves also matters, which is another area where publishing can greatly improve.

It has never been more difficult to earn money from writing books. According to the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, the median annual income for writers currently stands at around £7,000, a mean enough figure without qualification but especially when compared to the equivalent figure for UK full-time employment of £37,430.

In the history of literature, very few writers have been able to light cigars with £50 notes on their literary earnings, but it really has never been harder to make a living by the pen. Having the time to write has never been a greater luxury and being able to buy the hours required to sit down and produce a 100,000-word novel is practically an impossible task for all but the already wealthy.

I’m going purely on anecdotal evidence here, but having been part of the literary industry since the end of the last millennium it is clear that more and more published authors are people of independent financial means or have a partner earning enough to buy them the time they need to write.

That’s not to denigrate their work – finances aside, it has never been more difficult for any new writer who is not already a celebrity to break in to the traditional publishing world – so landing a book contract is a considerable achievement whoever you are. Yet those with existing financial safety nets have an unassailable advantage over those who don’t.

It is even more difficult for those taking the self-publishing route. While in the past, publishing your own work often meant the slightly shady world of vanity publishers, in which you paid to produce your own book rather than being paid for your craft, today, thanks to online publishing platforms like Amazon it has never been easier to see your book published, even just digitally, at little or no cost with the opportunity to earn from your work.

Yet writers of self-published books need exactly the same amount of time to create their work as those trying the traditional publishing route, and that time costs money that most writers cannot afford.

Add to this that the sheer volume of self-published work means only a tiny percentage of those authors will earn anything more than pennies. It makes this route just as financially hazardous as trying to secure a book contract.

Inevitably this limits the range of perspectives on the shelves of the nation’s bookshops. It has been excellent to see so many more women being published and, importantly, feted for their work in recent years, something this column has always been keen to trumpet.

There is still a long way to go before the dominance of the middle-aged white male author is ended once and for all, but the gender disparity is being improved all the time and long may that continue.

Yet gender is not the only issue where established voices dominate the literary world. Class is another. Publishing is about as middle-class as any industry gets, and in Britain that also means the white middle-class. Stroll through the offices of any major publishing house and you’ll notice an agreeably high proportion of women at the desks, more than in many other industries, even though the most senior roles will still most likely be occupied by blokes.

You may also notice they are almost exclusively white. Many will at least be aware of their relative privilege and try not to let it influence the range of work being commissioned, but inevitably minority voices become sidelined when they already face enough challenges before even producing work that reaches those publishing houses.

Working-class writers and writers from different ethnic backgrounds are woefully underrepresented on the shelves of Britain’s bookshops, but it will take more than a simple change in mindset to even up the numbers on that score.

It is often easy to forget that publishing is a commercial enterprise. Aspiring authors are often aghast when they see yet another celebrity releasing books in a blaze of publicity, or blockbusting bestsellers by authors they regard as poor writers.

It is frustrating when this happens, but publishing is not just a competition to find the best writers. It’s a business, first and last, and those celebrity kids’ books and grammatically questionable bonkbusters bring in the cash that gives an unknown author even a sliver of a chance of seeing their work on the shelves. That’s before even considering how those books sell in such numbers because people enjoy them.

If the current situation is going to change, there has to be a long-term commitment from areas beyond the publishing houses. All the creative industries have suffered in recent years because those in charge of the purse strings have no inkling of how important those industries are.

There is no simple solution, but one answer could be to look across the Irish Sea where the Republic of Ireland has an Artists’ Exemption from Income Tax scheme in which creative people, including authors, submit their work for evaluation. If the criteria are met there is no income tax to pay on that work for its entire lifetime.

Granted, that doesn’t help the author struggling to buy the time to produce that work in the first place, and the system is far from perfect, but it is indicative of an awareness of the value of the creative arts in Ireland.

The fact the scheme survived the merciless cuts that came about after the 2008 financial crash, albeit with the introduction of an earnings cap, demonstrates how Ireland acknowledges the vitality of its creative sector in a way Britain doesn’t.

Change that mindset even a little, and things could start to improve for those writers working at a grievous disadvantage by not being wealthy enough to set aside the hundreds of hours required to write a book.

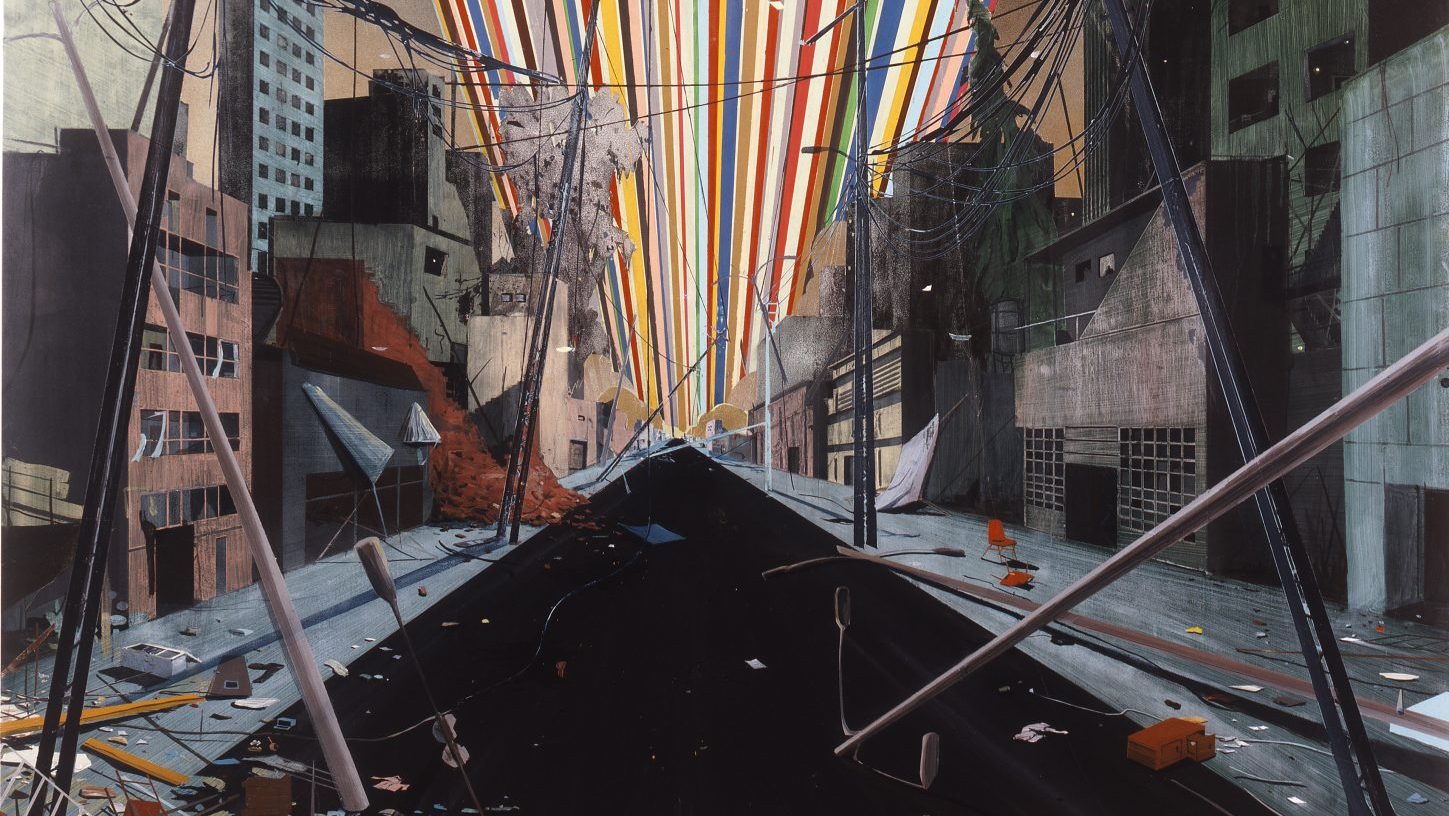

This outline of some of the issues facing authors, readers and publishers in 2025 could be an entire treatise but has been necessarily brief. Yet we haven’t even touched on what promises to be the largest challenge ever to face the literary world.

We’ll address the scourge of artificial intelligence next week.