Anglo-French rivalry may well be a 1,000-year story, but with entente cordiale very much in the air – witness the French army choir singing God Save the King in front of Keir Starmer on Armistice Day – we are perhaps more alike than we realise. We are two nations united by a common gloom.

A YouGov poll of seven European countries earlier this year found that France and the UK topped the ranking for pessimistic views – 80% of British respondents said their country was in a “very bad’ or ‘fairly bad’ state, and 71% of the French concurred. Meanwhile, a post-pandemic survey by the Paris-based Centre de Recherches Politiques de Sciences Po (CEVIPOF) found only 35% of the French and 38% of British are satisfied with their lives.

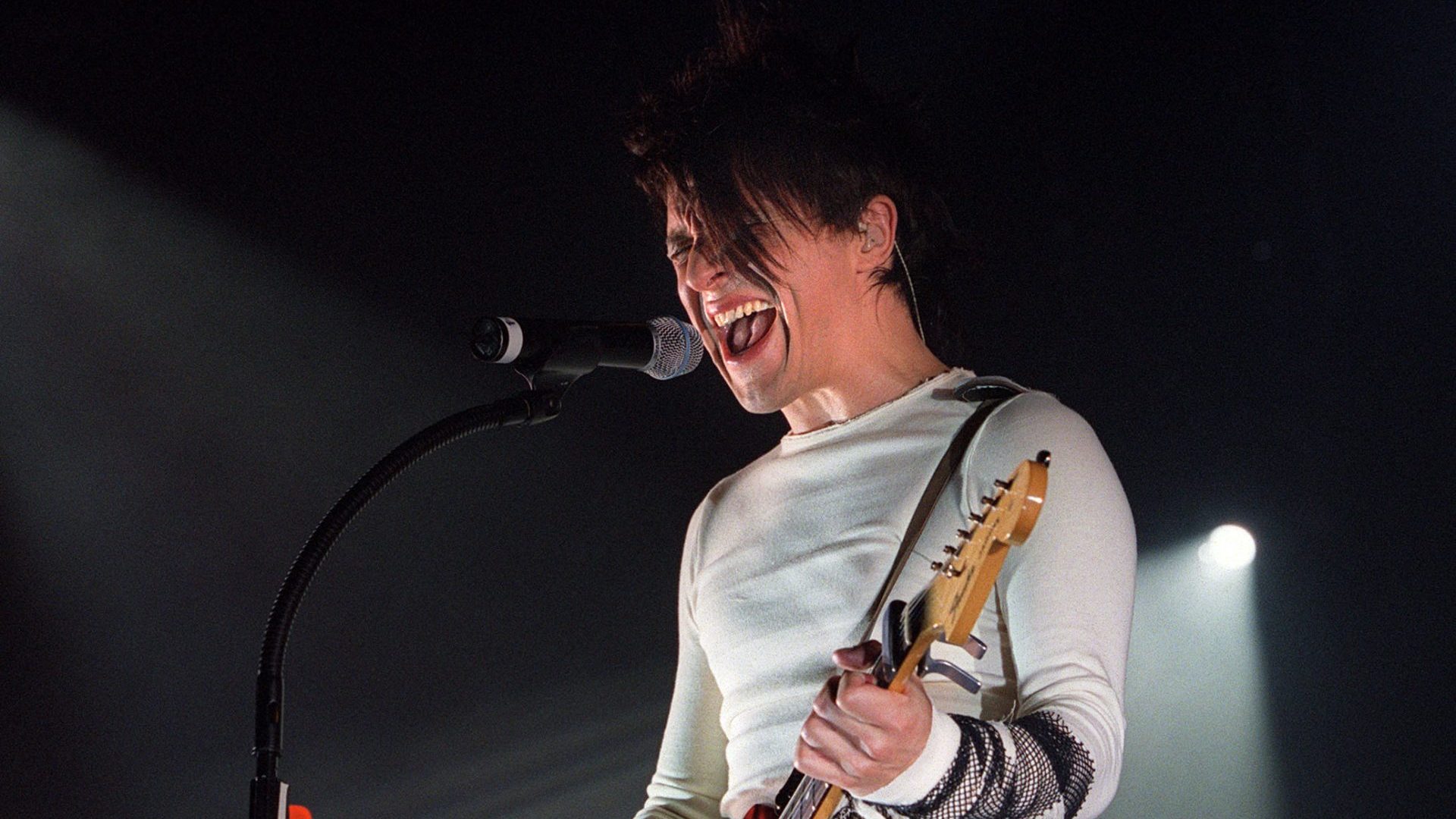

Miserabilism, it turns out, is a cross-Channel phenomenon. It also happens to be heavily associated with two of these nations’ greatest bands – The Cure, who released their first album in 16 years, Songs of a Lost World, earlier this month, and Indochine, who are busy promoting their 14th LP, Babel Babel. With 13 million album sales, Indochine are the most popular French band in history, and the two acts share an intertwined history.

Despite having recorded some downright euphoric songs, The Cure have been routinely derided as po-faced mope merchants, and Indochine have faced similar treatment, having adopted The Cure’s melancholically gothic look in their early days. But the influence ran deeper than that.

Indochine’s only remaining founding member, Nicola Sirkis, had listened to the Stones and Bowie growing up, but by the time Indochine played their first gig in September 1981, they had adopted key aspects of The Cure’s early post-punk sound. These had been showcased in the two UK-charting singles the band – the project of legendarily sardonic frontman, Robert Smith – had under their belts by the autumn of 1981. A Forest was a synth-driven, sinisterly gothic fairytale of phantoms, while Primary was no less icy but had a staccato guitar-led dynamism.

Powerful imagery and angular guitars similarly dominated Indochine’s first hit, L’Aventurier, released in late 1982. While it was leavened by some Depeche Mode-adjacent sparkly synths (they happened to have supported the British band in Paris earlier that year), the unforgiving drum machine and the spat-out vocals had The Cure’s fingerprints all over them, and it became an iconic track for a generation of French youth.

But Indochine, who have determinedly resisted singing in English, have always had an unmistakable Frenchness. L’Aventurier took its references from the series of French adventure novels of the 1950s and 60s featuring adventurer Bob Morane, while Sirkis’ love of French literature – Marguerite Duras, Apollinaire, Rimbaud – has influenced his songs that have ranged widely over life’s great questions.

Additionally, as stereotypes of the French might dictate, Indochine have explicitly embraced the political in their songs in a way The Cure never have (Robert Smith has instead worn his politics on his guitar, with the EU flag and ‘1978-2018’ among the slogans featuring there in the past). Indochine’s most recent single, the irresistibly anthemic Le chant des cygnes, is about the Mahsa Amini protests in Iran.

The Cure, for their part, have long had a strange affinity with France. The Cure in Orange, capturing them playing the Roman amphitheatre in that Provençal city in the summer of 1986, is one of rock’s great concert films. Their showing of four French Top 5 albums and two Top 20 singles has been impressive, and the release of the limited edition Live In France 2022 last month seemed to acknowledge a special relationship.

The French, meanwhile, have not hesitated to define The Cure in terms of misery – Le Monde opened their review of their penultimate French gig to date, in Liévin, Pas-de-Calais, in 2022, with ‘It was raining in the mining region. The conditions were ideal for watching The Cure’. In this association, The Cure and Indochine remain united and both new albums are perhaps genuinely the most pessimistic of their careers.

The Cure’s comeback single Alone is as musically ponderous and lyrical fatalistic (“This is the end of every song that we sing/ The fire burned out to ash / The stars grown dim with tears”) as anything they have ever done.

While Babel Babel’s danceable electronica is sonically very different, Sirkis – an almost exact contemporary of Robert Smith – almost exact contemporary, is quite clearly just as worried about the state of the world. The LP’s title track opens with a disorientating cacophony of news broadcasts and finds Sirkis singing: “No one understands us anymore/ No one hears us/ Languages so different/ Just pitching in the night of time.”

As both bands look towards major tours next year, perhaps the French and the English, united in gloom, might be a vision for a new Anglo-French entente miserable.