Russia is not a monolingual country. Scores of languages are spoken there

natively today in addition to Russian itself, and in most cases these minority

languages were in situ long before Russian speakers arrived on their territories.

The expansionist movement of Russian colonists, taking their language with them, began during the second half of the 16th century. Russian settlers spread out of their European homeland both northwards, towards the Arctic Ocean, and eastwards towards Siberia and the Far East, eventually reaching the Pacific by 1650.

By 1800, there were about 1 million Russian incomers in Siberia, and in 1850 this number was approaching 3 million. The languages and cultures of the scores of different peoples who had lived for centuries across the millions of square kilometres being appropriated by the Russians were often disregarded and marginalised. Under the Soviet Union, the marginalisation was partly reversed during the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, but this liberalisation did not always survive after Joseph Stalin came to power.

Of these non-Russian languages, there is no great need to be concerned

about the future of, for example, Chechen, which has something like 1.5 million speakers. But the position of some of Russia’s original languages

has become increasingly precarious, in spite of the official rights and

protections that they are nominally afforded.

According to Unesco, there are currently around 120 languages in Russia which are endangered to varying degrees. It seems that the languages of small, indigenous seminomadic or formerly semi-nomadic peoples are particularly vulnerable, and quite a few are already extinct.

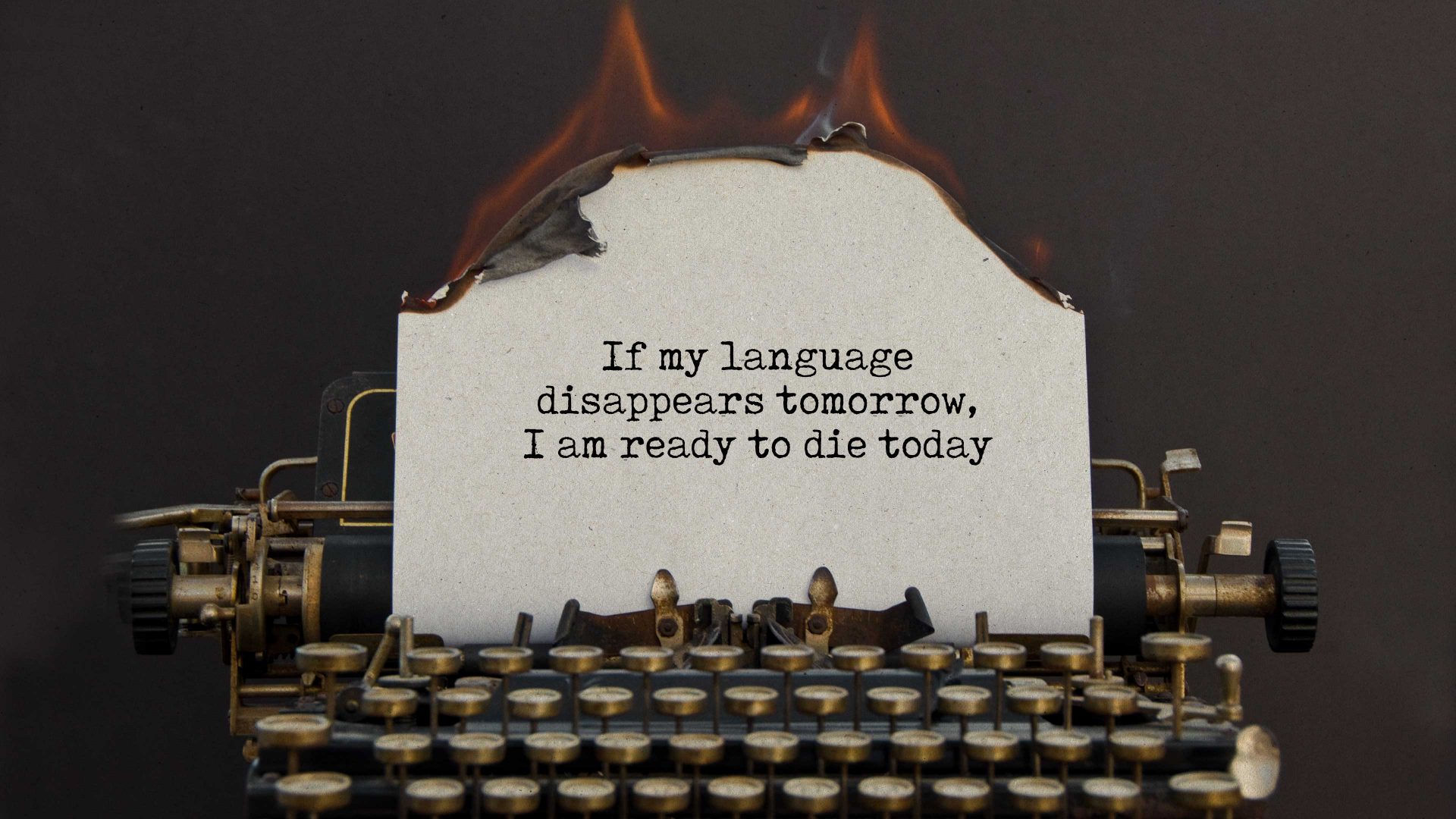

In 2019, a native speaker of one of these indigenous languages, Professor

Albert Razin, set fire to himself outside government buildings in Izhevsk, the capital of Udmurtia. He died from his burns soon afterwards. A banner he had been holding read: “If my language disappears tomorrow, I am ready

to die today”. This was a quotation from a speaker of another indigenous language, the poet Rasul Gamzatov, a native speaker of Azar, a Northeast

Caucasian language from Dagestan.

Udmurt is a Finno-Ugric language related to Finnish and Estonian and is spoken in the Republic of Udmurtia in the Volga district. Censuses indicate

that, between 2002 and 2010, the number of Udmurt speakers declined from 463,000 to 324,000. A figure of over 300,000 speakers looks rather healthy, but in fact a decline of 30% in just eight years is very alarming. In 2011, the United Nations’ Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger described Udmurt as “definitely endangered”, and recent studies indicate that the situation has not improved.

Prof Razin had earlier signed an open letter to local officials pleading with them not to support a new law abolishing the compulsory study of minority languages in Russia’s autonomous republics, including Udmurtia. Vladimir Putin had decreed that children should not be made to study languages which were not their native tongues, and education in minority languages would now become voluntary, leading to worries that many schools would just remove them from the curriculum altogether.

In 2018, the Council of Europe condemned this new law, noting that “over the past years a strong emphasis has been put on the Russian language and culture while minority languages and cultures appear to be marginalised”. It was doubtless fear of this marginalisation and subsequent language death which drove Prof Razin to despair.

NOMAD

The word nomad derives originally from the Ancient Greek form nomós ‘pasture’. Today we use the pronunciation “no-mad”, with a long o sound, but the original pronunciation in English was with the short o, “nommad”, which continued to appear as an option in British pronunciation dictionaries until the 1970s.