The first time I visited the town of Bronte in Sicily I discovered two things.

First: it’s where Italy’s premium pistachio is grown – a purplish, sweet variety dubbed the “green gold”, which is great for confectionery and is exported worldwide.

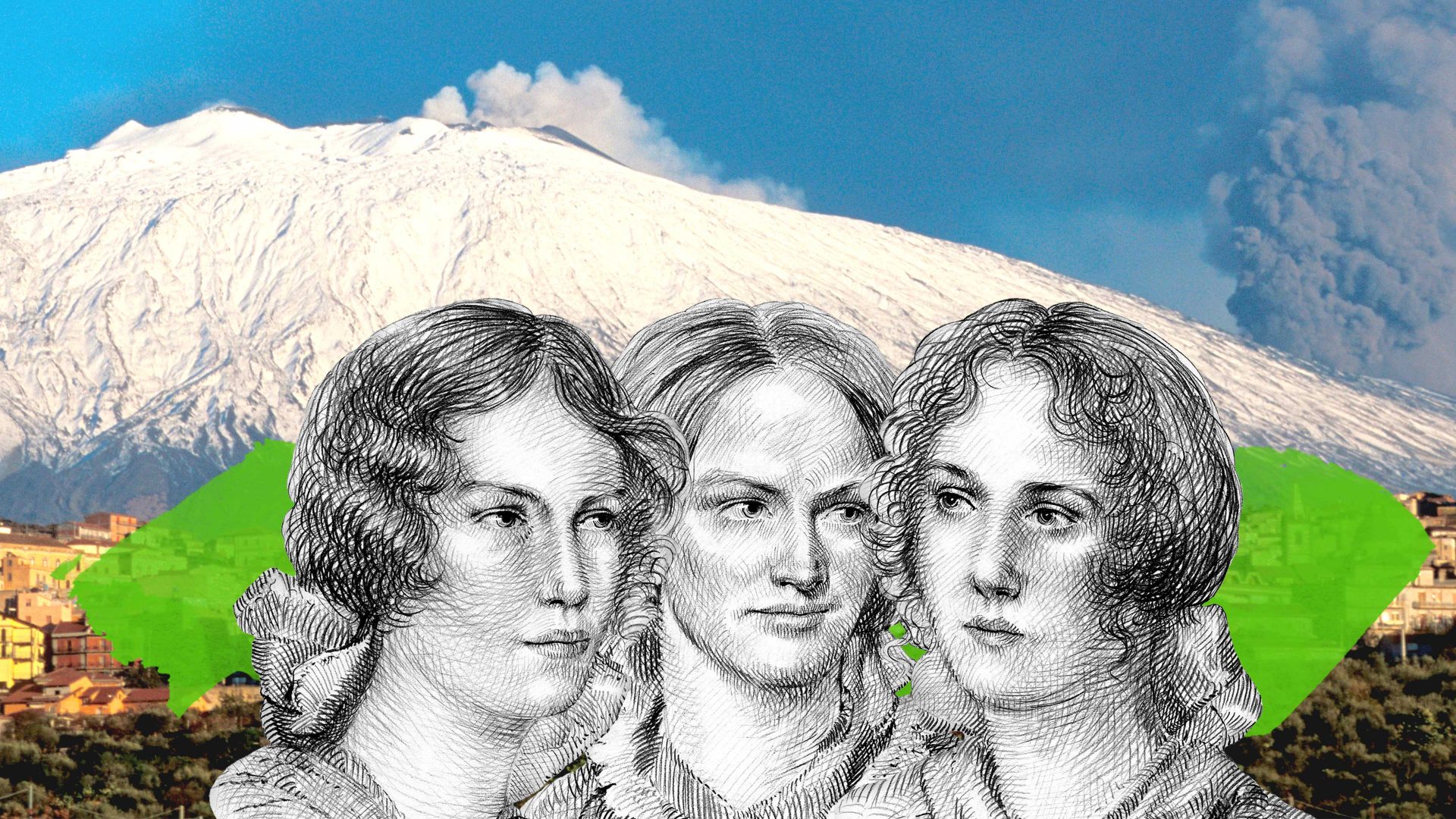

Second: it’s where the Brontë sisters got their name.

Lush estates of pistachio trees dot the pristine countryside, where shepherds and farmers tend to orchards and herds. The town is built on the slopes of the massive volcano Mount Etna, which erupts almost daily. The land is dark due to the past lava flows called sciare, and locals live in fearful respect of the volcano, which they call iddu (meaning “him” in the local dialect).

It’s a picturesque place where you can eat all-pistachio menus, including pasta and fish with pistachio, and hike up into the wild Nebrodi hills. But few people here know about the link between their town and the Brontës.

As I strolled along cobbled alleys, past Baroque churches and boutiques selling bags of pistachios, my guide, Antonio, told me, “Bronte was the name of the three-eyed Cyclops who, according to myth, was blinded by Odysseus when the Greek hero fled with his ship. But that’s not our biggest secret. It appears that the Brontë sisters’ father, an Irish Anglican minister called Patrick Brunty, was so fascinated by our town that he decided to rename his family after it.”

I could see why. From Brunty to Brontë – no big leap. He just added the diaeresis on the “e” to give the Italian pronunciation.

We walked past the cave believed to be the lair of the three-eyed monster, just outside the old district, and as I sipped on a pistachio granita (slushy) Antonio told me that, alas, Brunty never visited the Sicilian town of Bronte in his lifetime. None of his daughters did either. But it was out of his dedication to Lord Nelson that Brunty decided to change his name.

Nelson? What did he have to do with it all? The questions poured out of my mouth, and I could see my guide was getting fed up and the other participants on the tour annoyed, but I wanted to know everything.

“Nelson had been gifted the Sicilian estate of Bronte by the King of Naples,” Antonio explained. The king, it turns out, also gave Nelson “the title of Duke of Bronte to thank him for restoring the king to his throne in 1799 following Italy’s wave of revolutionary riots.” Apparently, letters written by Brunty confirm his developing fascination with this unknown Italian town with a name uncannily like his own.

At the bar on the main piazza I asked a lady sipping a pistachio-flavoured espresso if she had heard about the Brontës’ Sicilian roots, and whether she had ever read Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights. She said no, shaking her head, apparently uninterested.

In the butcher’s shop a stout man with blood smeared over his apron said he was proud that the Brontë sisters were fellow town folks. He told me local schools had started introducing the teaching of English literature, with a particular focus on the Brontë connection.

The butcher also said that the town’s mayor was trying to spread awareness of this “link” among residents and exploit it to lure British tourists.

Perhaps it’s sad that it always comes down to money. But then turning the Brontë sisters into moneymakers for a remote, pistachio-growing Sicilian town appeals to me. The definition of “Brontë country” is now due for a change.

Silvia Marchetti is a Roman journalist specialising in culture