From The Rite of Spring to Naked Lunch, from John Waters to Throbbing Gristle, part of the story of transgressive art is one of works that are much-discussed but little seen or heard beyond their devoted admirers. The last few weeks, though, have seen the deaths of two artists who shocked from the mainstream.

David Lynch, whose films took an adjusted £300m at the box office and whose Twin Peaks upended TV convention, left us on January 15 at 78. Two days earlier, in Cecina, Tuscany, Oliviero Toscani passed away at 82. The name may have been less familiar than that of the American weaver of dreams and nightmares but the work will have been even more widely seen. It was Toscani who for almost two decades spearheaded the Italian clothing brand Benetton’s spectacular and challenging poster campaigns, most famously a colourised version of a deathbed photograph of Aids activist David Kirby, Christlike in his suffering.

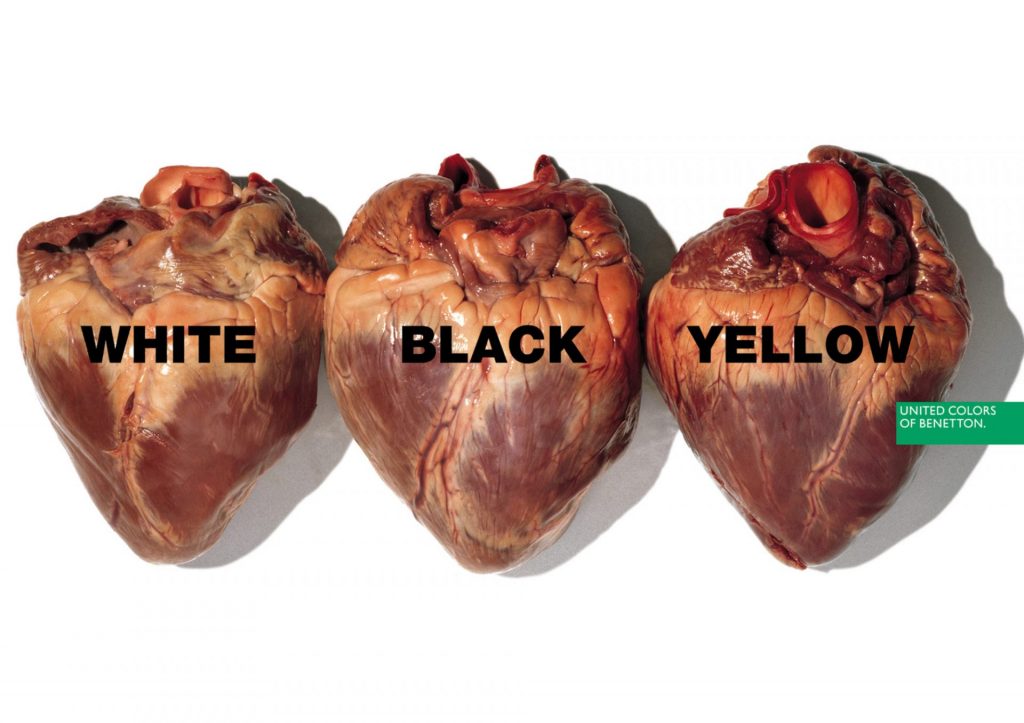

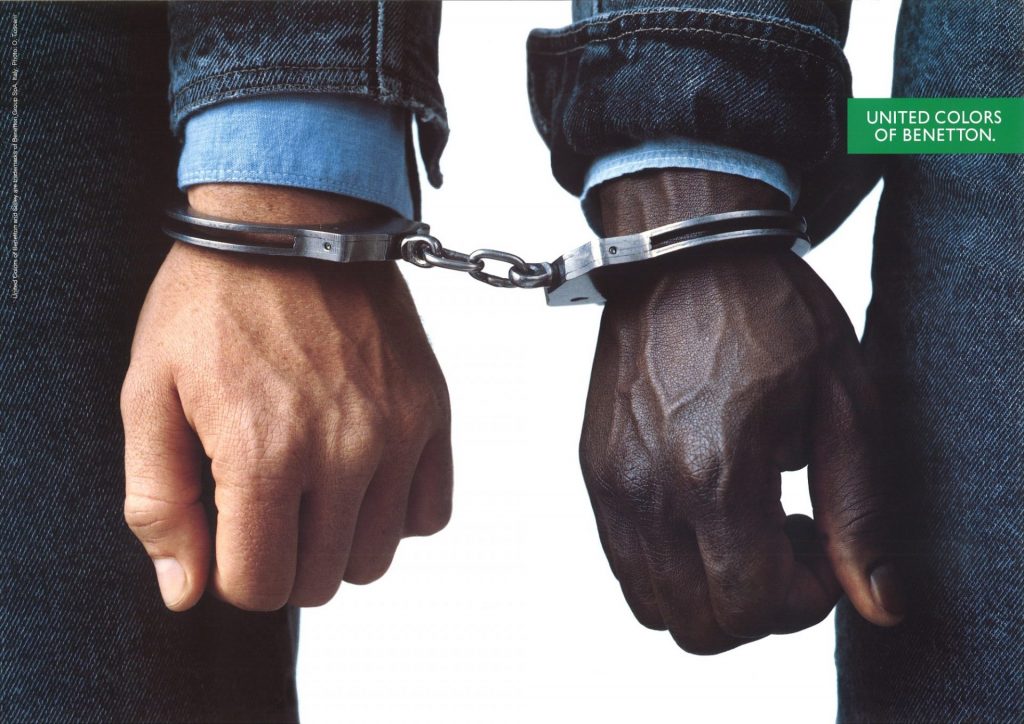

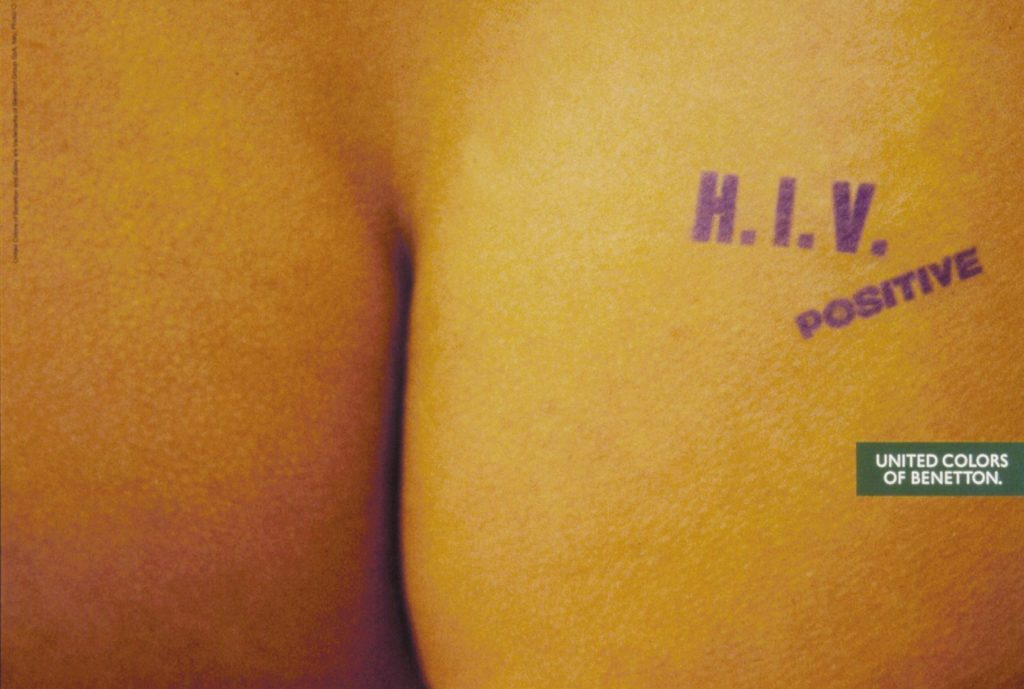

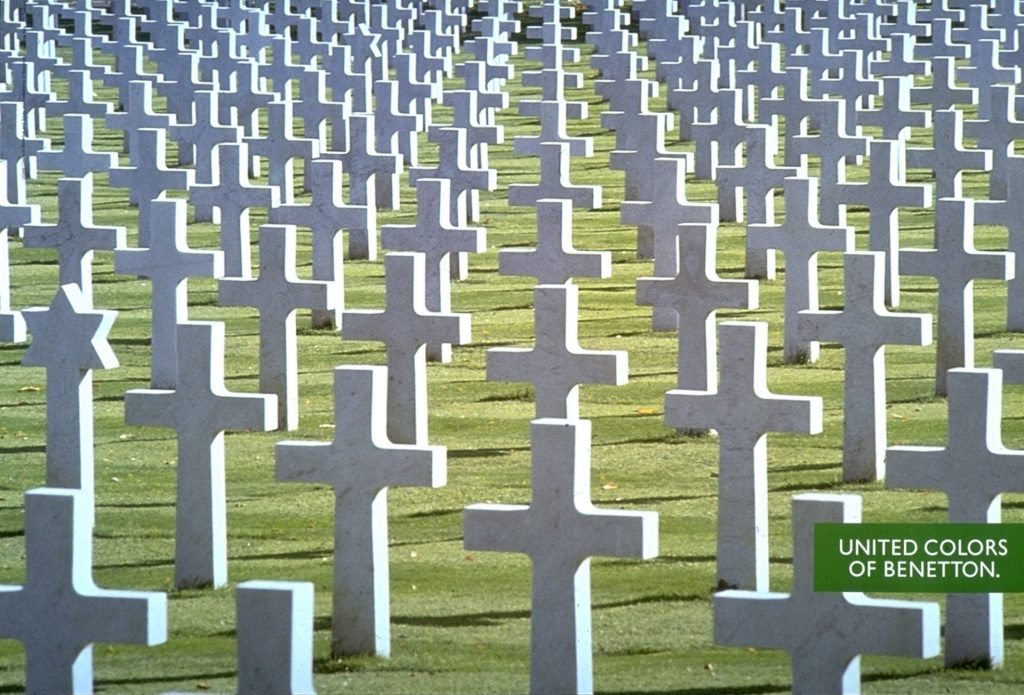

All photos: Oliviero Toscani/Benetton

This modern pietà caused a global sensation, but his family supported Toscani’s manipulation of the image and its use to sell clothing. “Benetton didn’t use us, or exploit us. We used them. Because of them, his photo was seen all over the world, and that’s exactly what David wanted,” they said.

Before Toscani, Benetton had been a byword for soft safety, with its advertising featuring smiling families wearing the company’s knitwear in a variety of colours. The only danger was provided by the company’s sponsorship of a Formula 1 team, but even that was headed by the sport’s golden boy, Michael Schumacher.

Now that was swept aside by a series of extraordinary images across the world’s billboards – a black and white lesbian couple wrapped in a blanket with their adopted Asian baby, a priest and nun kissing, a bloody newborn, a collection of multicoloured condoms; all in an 18-month period at the start of the 1990s. Toscani continued as art director until 2000, creating a string of memorable billboards and a lavish magazine, Colors.

Toscani had shock built into his system from the start. His father, Fedele, who worked for the newspaper Corriere della Sera, had taken some of the remarkable photographs of the executed Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci hanging upside down from a scaffold erected at a Milan service station in April 1945.

Days later, with the 14-year-old Oliviero accompanying his dad to the Miss Italy contest, Fedele was diverted to Mussolini’s home town of Predappio, where his body was to be buried.

Oliviero later remembered: “As soon as we got to the cemetery, my father handed me a Leica and said, “If you see something interesting, immortalise it right away.” I climbed between the crosses in the cemetery; there was a large crowd, black shirts, police, chaos and confusion.

“It was then that, a little to the side, I noticed a black Fiat 1400 parked away from curious eyes. Two carabinieri greeted a woman dressed entirely in black, her face hidden by a veil. I crawled closer. I tried to photograph her as she advanced. The fascists noticed me and pushed me away, but I managed to take the shot before falling.

“Back in Milan, my father developed the film. Surprisingly, he showed me the last negative and exclaimed: ‘Oliviero! Today you are the author of the photograph of the day!’ That’s how the photo of Rachele Mussolini (the dictator’s wife) in mourning went around the world. And that’s how I decided to become a photographer.”