When Rishi Sunak suggested – apparently with a straight face – that a good way to put Britain back on its feet after 12 years of [checks notes] Tory

government was to force schoolkids to do more maths for longer, the outpouring of scorn and disbelief that followed was quite enjoyable for the

arithmetically disinclined among us.

Of course a basic knowledge of mathematics is essential to everyday life. From household budgets to assessing your football team’s fading chances of reaching the play-offs, most of us have mastered all the numerical skills we’ll need barely a couple of years into secondary education.

As someone who dropped maths like a greased eel as soon as I possibly could I’ve never once looked back wishing I’d spent less time reading books and more doing trigonometry. Cormac McCarthy’s pair of new novels hasn’t altered that mindset entirely but has had me occasionally glancing uncertainly over my shoulder.

The Passenger and Stella Maris, published a few weeks apart at the end of last year, represent McCarthy’s first new fiction since 2006’s dystopian Pulitzer prize-winner The Road. While the two new titles are closely linked, featuring the same characters and telling different parts of the same story, publishing two novels in a calendar year is startlingly prolific for a writer who had until that point produced 10 in a career dating back almost six decades. They also

represent a considerable departure from his previous output and bear the

most obvious influence of his nearly 40-year association with a remarkable

scientific institution.

Most of McCarthy’s work is comprised of moralistic tales of good versus evil set in the southwest of the United States, stories like Blood Meridian and No Country For Old Men populated by losers and ne’er-do-wells, all existential frustration and Weltschmerz, graphic outbursts of extreme violence and the sense there’s an inherent nastiness lurking at the core of the human condition. Pitched somewhere between Southern Gothic and modern westerns, McCarthy’s books have always tended towards the blokey, too, his women characters generally perfunctory and superficial.

In contrast, The Passenger and Stella Maris are novels of ideas that tackle whopping questions: the nature of consciousness and the thin line between genius and madness, the clash of faiths when religion comes up against science, the moral legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and deep philosophical explorations of mathematics and physics. They even have a strong woman lead character who may be the closest we have in his fiction to representing McCarthy himself.

The books focus on a brother and sister, Bobby and Alicia Western, thumpingly intelligent children of a physicist who was at the heart of the Manhattan Project. Contrasting formats just about vindicate splitting the story into to two books rather than one (Picador are a bit cheeky charging

£20 for each, however, especially when Stella Maris comes in at well under 200 pages) but the two narratives combine into an overarching tale of intellectual brilliance and ultimate frustration, mental illness, disenchantment, grief and taboo love.

In The Passenger, the first to be published, the emphasis is on Bobby. It’s the early 1980s and he’s a salvage diver in New Orleans sent to explore the wreckage of a chartered jet that crashed into the sea off the Mississippi

coast where he discovers one of the passengers’ bodies is missing along with the black box recorder and pilot’s flight bag. This gripping opening appears to set up a straightforward thriller, especially when shadowy men in suits begin harassing Bobby in the weeks that follow, but it’s not a major spoiler to say the sunken jet mystery is never resolved or that we never learn the significance of the eponymous passenger. If that narrative thread fizzles out the novel ranges so widely that it doesn’t seem to matter.

Bobby is still grieving the loss of his sister Alicia, who took her own life in 1972 while a patient at the Stella Maris psychiatric hospital in Wisconsin. The

legacy of his father’s work with Robert J Oppenheimer also hangs over him,

not to mention the fact that he and his sister were deeply in love with each other, making his life a series of aimless dabbles in dangerous pursuits that leave fate’s door ajar to possible self-destruction – racing cars, salvage diving, spending a freezing winter alone in a remote, ramshackle cabin.

Stella Maris, meanwhile, is presented as transcripts of conversations between Alicia and her psychotherapist in the months leading up to her suicide. The astonishingly gifted 20-year-old mathematician has been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia having had vivid hallucinations of a shady Vaudevillian she calls The Kid, four feet tall with flippers for arms, since the age of 12. Her encounters with the Kid and the troupe of freaks and hoofers that follows him around intersperse Bobby’s story in long italicised sections of The Passenger but are discussed in detail with the therapist in Stella Maris along with how Alicia’s genius for mathematics and her quest to push its boundaries have caused or at least contributed to the breakdown of her mental health. She’s also in love with Bobby who, at the time of this novel, is in a coma after crashing a racing car in Italy.

Alicia’s conversations with her therapist delve deep into the conundrums and histories of maths, string theory and quantum physics revealing that like most geniuses she is frustrated that so few people in the world match her intellectually. She’s also a gifted musician, using most of a considerable family legacy to buy an Amati violin for more than a quarter of a million dollars only to give up when she realised she would never be one of the world’s best violinists.

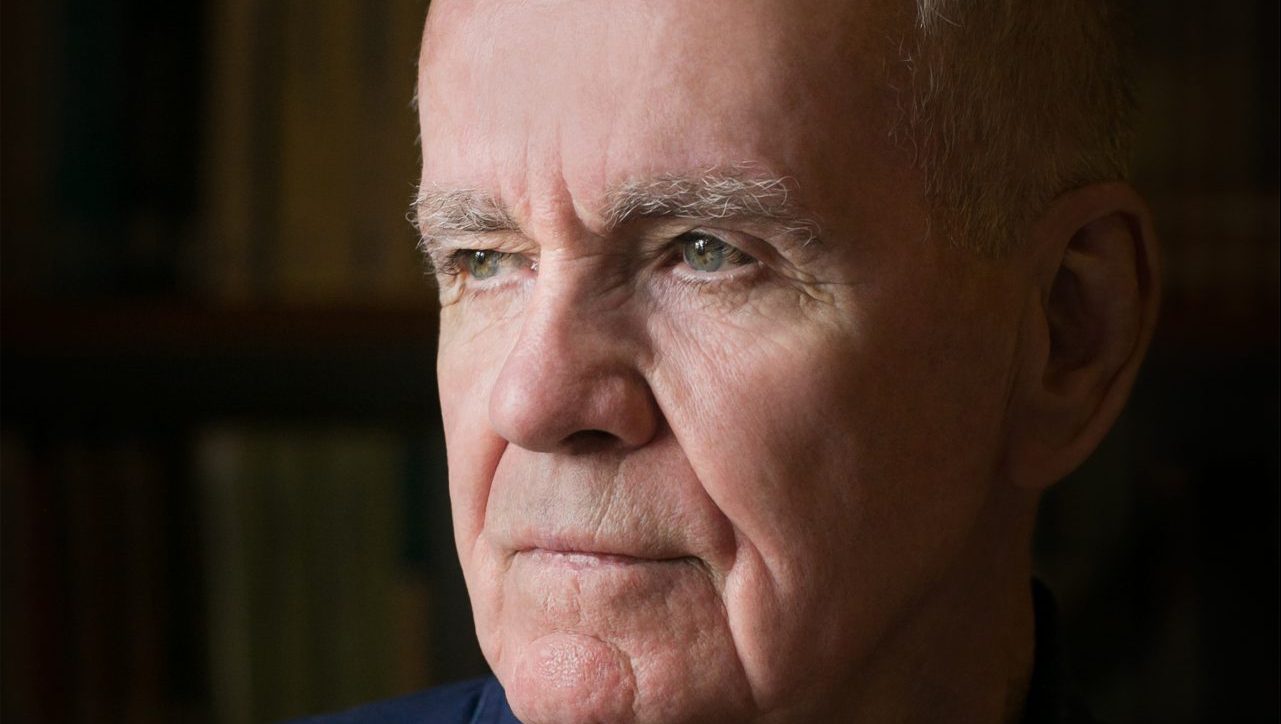

Stella Maris is where McCarthy demonstrates his own thundering scientific and mathematical intelligence. Despite being feted as one of the greatest novelists of the contemporary western canon he has always eschewed the company of writers and rarely engaged with the literary world. He’s given only a handful of interviews, especially since All The Pretty Horses catapulted him into the international limelight in the early 1990s.

There was a 1992 interview with the New York Times and another with Vanity Fair in 2005 – both with the same journalist, a personal friend – as well as an awkward 2007 television encounter with Oprah Winfrey when The Road was selected for her book club. But that’s it. He’s never given a public reading, never attended a literary festival, has no mobile phone and no computer, writing his novels on a manual Olivetti typewriter. He once responded to a request by an acquaintance for his contact details with: “I don’t have contact details”.

Through Alicia, his first-ever woman protagonist, McCarthy can disburse some of the complicated mathematical and scientific knowledge he’s acquired over many decades through his close involvement with the Santa Fe

Institute, an independent scientific research facility founded in 1984 by McCarthy’s great friend, the particle physicist Murray Gell-Mann. The writer has been a significant presence at the institute for nearly 40 years, clacking away at his typewriter in a small office while elsewhere in the building some of the world’s finest mathematical and scientific minds grapple with highfalutin theories and ideas.

Sometimes McCarthy has even proofread and copy-edited books by scientists and mathematicians connected to the institute having never granted as much as a cover endorsement to a fellow novelist.

“He’s a permanent fixture in our community,” said Professor David Krakauer, evolutionary theorist, friend of McCarthy and leading figure at the

non-profit institute (in 2009 McCarthy auctioned his faithful Olivetti typewriter in aid of the establishment and raised a shade over $250,000. He

replaced it with an identical, second-hand model for $11).

“I like being around smart, interesting people and the people who come here are among the smartest, most interesting people on the planet,” McCarthy said in his 2005 Vanity Fair interview. “What physicists did in the

20th century was one of the most extraordinary flowerings ever in the

human enterprise. They changed reality. And most of them were just kids.”

It almost feels wrong calling these “new” novels as McCarthy appears to have been working on them for decades. Oblique references to what became The Passenger and Stella Maris date back almost 40 years, giving one the sense that on the threshold of his tenth decade – he’s 89 years old – McCarthy intends these books to be his literary and philosophical testament, one that pays tribute to the great physicists and mathematicians, the Santa Fe Institute and the friends he’s made there over almost half a lifetime.

There’s almost a wistfulness in the books, a sense that, given his time over again, McCarthy would have become a mathematician or physicist instead of a novelist. It was when he received the McArthur Fellowship award in 1981 ($236,000, almost exactly what Alicia paid for her Amati violin) that he began mixing with the great scientific minds that have stimulated the second half of his life and confirmed his antipathy to the flakier world of the literati.

As Alicia says in McCarthy’s jab in the chest to those of us laughing up our sleeves at the prime minister’s maths plan: “When you’re talking about intelligence you’re talking about number. A claim that the mathless are quick to frown upon. It’s about calculation and the nature of calculation. Verbal intelligence will only take you so far.”

This is a novelist at the peak of his powers on the threshold of his tenth decade, curiosity undimmed, squaring up to the great questions of science

alongside the great minds and establishment that have galvanised him like nothing else.

The Passenger and Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy are published by Picador, each priced £20