It is February 1651 and a man is hurrying home from the fields. “Down the narrow lanes between homesteads he glimpses the moonlit river, in spate from the thaw. The air is ice-sharp, tinged with smoke and resin, the only sounds the rush of water, the muffled bellows of cattle and the distant cry of a wolf.”

The man eventually gets home, climbs into bed and closes his eyes. “But then he’s awake, the room suffused with light. He sits up rigid with fear, sensing movement on the floor. He forces himself to look. Three snakes are slithering towards him.”

One of the snakes approaches. He fights it off, but it comes back and bites him on the forehead. Then, “in the deep voice of a man – a voice he recognises – the snake breathes the word ‘death’.” And then, suddenly, the room returns to darkness, and the snakes are gone. So begins The Ruin of all Witches by Malcolm Gaskill, a historical account of events that took place over 300 years ago in Springfield, a small settlement on the edge of the New England wilderness.

The town’s inhabitants are terrified by a string of unusual events, including sightings of strange, horrific animals, the discolouration of cows’ milk, the unexplained sinking of boats, windmills collapsing on windless days, mysteriously spoiled food and unexplained deaths. People have seen strange lights in the sky and the figure of a woman wandering alone in the marshes at night. The atmosphere in Springfield darkens from suspicion into outright paranoia until eventually the people come to the only possible conclusion – there is a witch at work.

Suspicion falls on two Springfield residents, Hugh Parsons, a brickmaker, and his wife, Mary. But Hugh and Mary do not sell strange potions, or sit cackling beside a cauldron. Hugh is gruff and unfriendly and perhaps a little weird. He turns up at people’s houses in the middle of the night for no apparent reason. He is argumentative, always haggling over business arrangements, and on the death of one of his children he shows a surprising lack of emotion. Mary, on the other hand, is withdrawn and sullen, but prone to strange outbursts and sudden changes of mood.

The couple are eventually accused of witchcraft, with terrible consequences for both of them, and this account is a brilliant evocation of the suspicion and panic leading to their denunciation and arrest. It is a world in which “adversaries, naturally powerless and forbidden to use violence, might resort to magic to get their own way.” Fright was taken for the slightest of reasons, and deep significance read into the smallest occurrences. “Poor women who were refused alms on the doorstep, for instance, naturally mumbled harmless imprecations, which then were taken seriously by the refusers, especially if bad luck ensued.” The psychological effects of this were severe. “Fear incubated guilt,” Gaskill writes, “which was projected and returned as anger.” And once it was enraged, the mob wanted blood.

The events in Springfield were just one witch-hunt of many. Fear of witchcraft surged through the English colonies of North America, including, most famously, at Salem. Back in the old country, the English were just as susceptible to witch panics as the colonists of the new world. In 1616, in the Essex parish of Navestock, villagers “accused a widow and another woman – probably her daughter – of magical murder and entertaining demons.” In another hamlet, close by, a glover and his wife were accused of “bewitching to death a man, a pig and three horses.” In Chelmsford, a woman was hanged “for using a skull taken from a grave to cast a spell which killed a father and son and consumed a woman’s body.”

The Salem trial, along with the East Anglian witch-hunts of the 1640s, led by the famous Witchfinder General, have become famous on account of their portrayal on film. And yet England and the American colonies were not the true centre of the early-modern witch trials. The worst outbreaks of all took place in continental Europe.

“Things in Anglo-America are rather restrained in comparison,” Gaskill told me when I spoke to him by phone. Gaskill, an emeritus professor of early modern history at the University of East Anglia, explained that the most horrific outbursts of witch-hunting were in southern Germany, in the small independent states of the Holy Roman Empire.

The southern German city states were “confessional” states, meaning that inhabitants could be either Catholic or Protestant. As Gaskill explains, “these were regions of intense Reformation and Counter-Reformation tension”. This deep sense of religious insecurity, combined with a suspicion that others were distorting the gospel for their own ends, increased the impression that the devil was on the prowl. The witch panics of southern Germany emerged from this climate of religious fear. Two particular examples were the cities of Bamberg and Würzburg. “Both were insecure Catholic prince-bishoprics, which between the mid-1620s and early 1630s saw intense persecution of witches,” said Gaskill. “This resulted in about 1,000 executions each. The punishment, typically, was burning at the stake – in England and America it was hanging – although many people died in custody.”

The Würzburg outbreak resulted in one of the largest mass executions in Europe. Men, women and children were all cast into the flames. As Gaskill writes in his book: “Witches confessed to meeting the devil, accepting his offers, even to copulating with him. But the devil couldn’t be everywhere so he relied on an army of imps. They came in many shapes – insects, rodents, reptiles, dogs, even children.” In Würzburg, the city authorities burned witches nine at a time.

In southern Germany, the hunts, the accusations, the trials and the executions “generated a terrifying vortex,” Gaskill said, “where more and more people were tortured, leading to more and more denunciations, arrests, and tortured confessions.” Not everyone was happy about this. The Chancellor of Würzburg wrote to a friend in August 1629, describing despairingly how clerics, doctors, law students, fair maidens, the young and the old, men and women, were being sucked into the seemingly unstoppable purge. “Ah, the woe and misery of it!” he lamented.

So, what really was going on in these extraordinary, terrifying outbreaks of supernatural terror? The people of the 17th century believed some very different things to us – but really they were not that different. They still wanted comforts, success, money, they wanted their families to be safe and healthy, to have nice homes and businesses. They were intelligent, energetic, skilful people, who built houses, jails, churches, cities and complex societies, and were able to operate businesses that traded across the Atlantic Ocean. It’s tempting to see witch panics as a result of some sort of insanity, hysteria, or perhaps even the accidental consumption of magic mushrooms, a theory advanced to explain some of the wilder, hallucinatory accusations that often seemed to accompany them.

But perhaps these outbreaks are better understood as the result of a buildup of extreme psychological pressure. As the book shows in terrible detail, life in the 17th century was brutal, for the people of Springfield in New England, and across Europe. Children died young. Work mostly consisted of relentless, back-breaking labour. Disease was a constant part of life and was especially dangerous for children, many of whom died young. Excessive rains, or drought, or an unseasonal frost could ruin the harvest, leading to poverty, hunger – even starvation. Women were expected to do hard manual work, even when pregnant, and all of this was overshadowed by intense arguments over religion that, across Europe, broke out in the frenzied violence of the Thirty Years’ War.

Europe’s witch-hunts emerged from this background of suffering, slaughter and spiritual angst. But the prosecution of witches was not an arbitrary, unfocused process, or a result of the trumped-up malice of feuding neighbours trying to get rid of each other. Trials were highly bureaucratic, took up huge amounts of time and resources, and were expensive. “You’ve got to really want to have one,” said Gaskell. “They’ve got to be properly funded. Quite often witch-hunts ended abruptly, not because people came to their senses but they decided the disorder being created by the witch hunt was greater than the perceived disorder of the witchcraft they were trying to eradicate”.

For this reason, the era of witch panics passed relatively quickly. In Salem, people soon felt uneasy at the extremity of recent events. The southern German witch panics ended because of intervention from the authorities, which wanted to close down the unsavoury spectacle.

The witch trials that took place in the borderlands of the French-Spanish Basque country came to an especially unexpected end – they were shut down by the Spanish Inquisition. These hunts had originally started as local initiatives, but when the Inquisition started to take an interest it didn’t like what it found. “When people took it upon themselves to purge witches,” Gaskill said, “it rather stood on the toes of the central authorities. They wanted to do it themselves.”

What can we make of these strange and brutal goings-on? People tend to regard the stories of Europe and the New World’s witch panic as part of our primitive past, relics of a savage, pre-scientific society. But perhaps the instincts they reveal are more familiar than we realise. “We tend to think of our ancestors as being rather jumpy and intemperate,” said Gaskill. “Actually, they are a bit more like us that we would like to pretend.” It’s a rather startling and unsettling thought, particularly in light of recent events. Britain has recently witnessed the spectacle of a woman being identified as the source of all our problems. That woman – Liz Truss – was exposed, denounced and dispatched, in order that our society could move forward and prosper.

“You can always draw these parallels – they have their limits,” said Gaskill. “But there’s something even more striking than the defenestration of Liz Truss,” he says. “It’s about the Tory Party. There’s a concept called collective narcissism. It’s a tribal identity that is driven by outward prejudice rather than inward loyalty.” The effect of this is to lower the collective self-esteem of a group, so that in the end it comes to be driven by shame, suspicion and obsession, with a particular fixation on the idea of enemies within.

“I thought this perfectly describes Springfield, but it perfectly describes the Tory Party as well – this intense, bitter in-fighting.” The group manifests its identity through a kind of paranoia and aggression. “And that aggression has to have its target and it has to be projected.”

The psychoanalyst Melanie Klein developed the idea of “projective identification”, which meant that an individual carries a deep shame at being a terrible person and their sense of self-loathing is so intense that they project it outwards. “It’s unbearable, and actually you invest some other person with exactly the same qualities you can’t stand in yourself.”

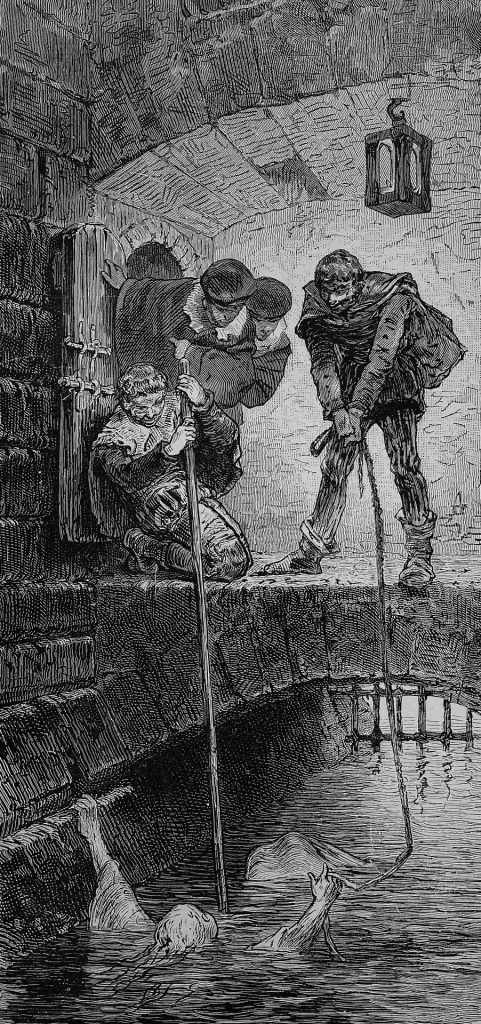

As Gaskill shows in The Ruin of all Witches, the consequences of that projective identification were accusations of witchcraft, made in a wild colonial border town against Hugh and Mary Parsons, a couple who were so antagonising precisely because they embodied in concentrated form all of the instincts of the colonial society itself. They were dragged to Boston in chains and held in horrendous conditions as they awaited trial. But by the end of it all, the town of Springfield, and the inhabitants who had accused and rejected them, benefited nothing from these events. So why did they do it?

“Witchcraft accusations make people feel part of a group. It increases a sense of community. But it’s short lived,” said Gaskill. “After the witches are gone, the same people carry on fighting and hating each other in just the same way as before.

“When a community like that, or when a political party, purges itself, then actually you are just on to the next thing, because there’s always some orthodoxy to defend, or some new heresy to vilify. Groups do that. Maybe we are all like that.”