Imagine briefing a current-age Rip Van Winkle who has just awoken from a nap that started in 2012. How would you explain to him the changes the world has faced in these 10 years?

You’d start with Ukraine, certainly, and the way climate change has become a climate emergency. You’d tell him that artificial intelligence has gone from a speculative possibility to an everyday reality and that social media has installed itself in the centre of the global public square – he’d have to learn what TikTok and Snapchat are. Then you’d tell him about the pandemic, Britain’s chaotic exit from the EU and the resurgence of aggressive nationalism in China and Russia, without forgetting, of course, that for four very strange years Donald Trump – yes, that Donald Trump – occupied the Oval Office.

All of those things would be true, but they would obscure a most consequential one: the global crisis of democracy. All around the world, democracy is under pressure from the inside. Sometimes it buckles, sometimes it holds. Average scores in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index have fallen year-on-year since 2014, and according to Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Index, more countries have seen declines than advances in freedom every year since 2006.

The issue is not that there are more outright dictatorships, it’s that democracies we used to think of as rocksolid have come under unprecedented pressure, and several – including the US – show distressing signs of deconsolidating. In 2012, when our Rip fell asleep, around two out of every five people lived in countries that Freedom House classified as fully free, and about one in five lived in partly free countries. Today, those proportions have reversed: two in five live in partly free countries, while just one in five people worldwide now live in countries or territories that are fully free.

Consider this modern paradox: since 2012 the world has had more and more elections but less and less democracy. Why is democracy bombing while elections of all kinds are booming? It’s because today’s autocrats don’t do away with elections altogether: they keep them around, but quietly undermine them until they’re rendered meaningless. They bar key opponents from standing for office, as Alexander Lukashenko did in Belarus in 2020 and Daniel Ortega did in Nicaragua a year later. Or they massively gerrymander constituency maps to tilt the outcome in their direction, as governor Ron DeSantis is doing in Florida and prime minister Viktor Orbán did in Hungary, beginning in 2014. Or they intimidate and bully journalists and distort coverage of the incumbent’s campaign, as Sebastian Kurz did in Austria and Narendra Modi is doing in India.

The results are odd pantomimes of democracy that look and feel like elections but aren’t. Think of them as pseudo-elections. In the same way that pseudo-science often mimics the outward trappings of science to appropriate its credibility while actually undermining it, pseudoelections ape democracy in order to do away with it.

And the phenomenon isn’t limited to elections. These new autocrats also employ pseudo-law, writing legislation and implementing judicial procedures that are designed to look and feel like the rule of law but aren’t. Courts are stacked with die-hard loyalists, as Evo Morales did in Bolivia and Donald Trump did in the US, or have their powers and independence sharply curtailed, as the Law and Justice government did in Poland and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has done in Turkey. They introduce norms and regulations that ostensibly apply to everyone but, in practice, apply only to their political rivals – to harass them, or to themselves – to extend their own power. Slowly, stealthily, pseudo-law subverts the justice system, eating away at the fabric of the rule of law until it’s in tatters.

In the information space too, new, stealthier ways of controlling information have taken the place of the old-school censor. Dissident media companies are shut down only as a last resort, more often they are regulated into submission. Tax inspectors turn up three times a week to audit the minutiae of their accounting. Newspapers in Argentina and Venezuala are administratively blocked from buying newsprint. Content regulators issue fine after fine, often for behaviour ostensibly unrelated to the outlet’s political line. Shadowy investors turn up with too-good-to-be-true offers to take the now money-losing outlets, buy them, and begin to align their editorial line to what the government wants the audience to know. The result isn’t censorship, exactly, as much as a pseudo-press: with all of the outward trappings of journalism and none of its content.

Pseudo-elections, pseudo-law and a pseudo-press together are the recipe for pseudo-democracy: a zombified version of democracy that think tanks qualify as “partly free” because they still retain vestigial elements of the democracies they used to be, or at least pretend to.

Why do they act like this?

In my new book, The Revenge of Power, I argue that all of these developments are symptoms of the spread of a new model for undermining democracy that is rapidly circulating around the world. Across widely differing geographies, our era’s aspiring autocrats have converged on the same techniques to gain power democratically and then undermine the democratic systems they run from within. Their goal is every autocrat’s goal: to wield power without limits. They don’t always succeed, but even where they fail, they leave behind weakened and vulnerable institutions, raising their chances of success on the next try.

What are these techniques? And what can we do about them?

I can sum them up in three words: populism, polarisation and post-truth. Each of these 3Ps has been around for centuries in one form or another, but 21st-century autocrats are finding new ways to deploy them together cohesively, leveraging new technologies to multiply their power.

The starting point is populism, which is not an ideology but rather a toolbox for gaining and wielding power that can be coupled with virtually any ideology. Populists are leaders who portray the basic fault line in society as the conflict between a corrupt elite and a virtuous, long-suffering people. As a framing device, this can be easily adaptable to local circumstances, both ideological, national and religious. Narendra Modi’s populism in India identifies the pure people as vegetarian Hindus and the corrupt elite as beef-eating Muslims and foreigners. Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro’s populism identifies the people as honest and hard-working and the corrupt elite as the globalised, left-leaning, political-managerial class that resides in Brazil’s big cities. The specifics don’t matter as much as the structure of the pitch: you are good, they are bad, and you need me to protect you from them.

Populism is a poisonous frame to put on any political dispute, but its destructive potential is made that much worse when coupled with the second P: polarisation. Polarisation strategies seek to heighten political tensions by turning any and every political discussion into a referendum on one thing: are you on the side of righteous people and the leader or are you on the side of the rotten, voracious elite? Polarised political systems stamp out the neutral spaces between opponents, delegitimising any attempt at pragmatic compromise and peaceful cohabitation between the sides. A talented populist at the helm of a determined campaign of polarisation can quickly put democratic institutions under considerable pressure. Sometimes the institutions hold. Sometimes they do not.

But that’s not all. Today’s autocrats, and those who aspire to join their ranks, are often masters of post-truth. By this I refer not merely to lying or stretching the truth, which all political leaders do, but to something far deeper and more insidious. Post-truth sets out to distort the public sphere to such an extreme that people lose sight of the distinction between truth and lies. Sometimes they do this through the kinds of “firehose of falsehood” technique pioneered by Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin, where a relentless barrage of obvious lies, always told with a straight face, overwhelms viewers’ faculties. Or they might use sophisticated social media influence campaigns based on carefully constructed online “bot-armies” sent out to magnify the influence of untrue or polarising claims, or to trash the reputations of opponents. In either case, the goal is not so much to convince the audience of a given falsehood, but to mire them in a morass of fear, uncertainty and doubt: a feeling, summarised in the title of Peter Pomerantsev’s recent book, that Nothing is True and Everything is Possible.

Populism, polarisation, post-truth. The formula has worked remarkably well around the world for those seeking to deconsolidate even democracies we once perceived as fully mature. And Europe is far from exempt.

3P techniques have a long European pedigree, and not only because Putin is by far the most successful and pernicious of the world’s 3P autocrats. East and west, north and south, 3P techniques have destabilised regions and whole countries, turning each election into an existential crisis for more and more democracies.

Probably the earliest adopter of the strategy was Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, who appended populist framing to a relentless campaign of vilification against the “men in togas” – the judges, who inconveniently persisted in investigating a long list of business scandals he was involved in. Berlusconi launched an unprecedented assault on Italy’s media landscape, creating a post-truth public sphere before the internet had even gone mainstream.

To be sure, Berlusconi did not succeed in degrading Italy’s democracy beyond repair. He could be voted out of power, and he was on more than one occasion. Still, once populism, polarisation and post-truth strategies are set loose on a political system, they can continue to corrode it long after the leader who started them is out of the picture. In Berlusconi’s wake, Italy would fall prey to successive populist pretenders including not just the far-right La Lega but a true anomaly: a centrist populist movement, the Five-Star Movement, which was somehow at once militantly environmentalist and pro-Russia. Berlusconi may not have clung on to power indefinitely, but his spell in Chigi Palace left Italian democracy deeply destabilised.

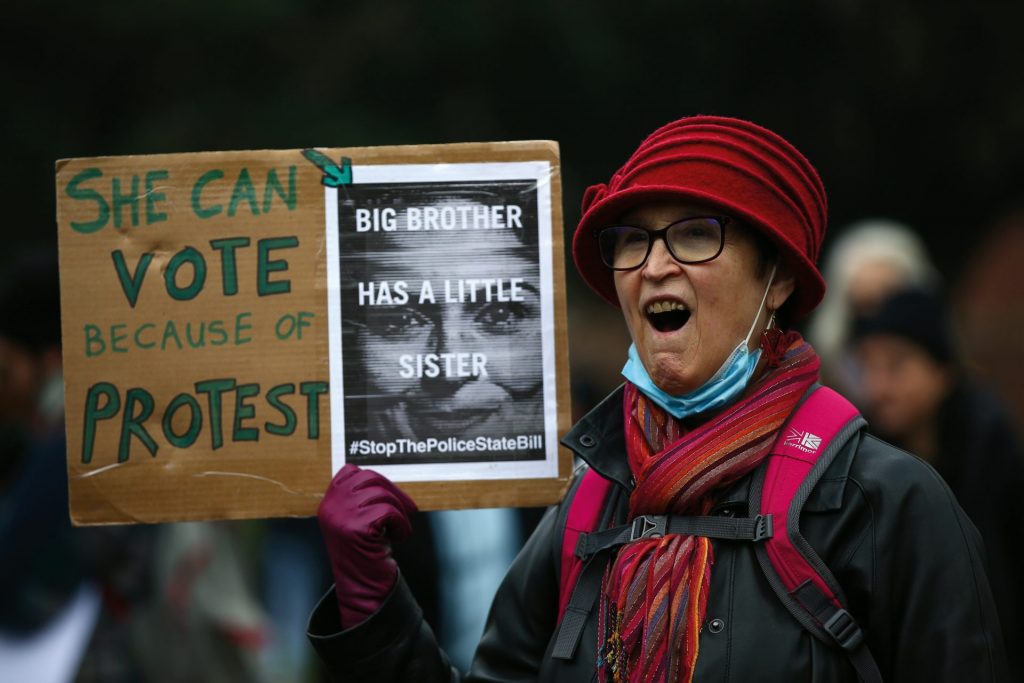

But perhaps the most unexpected victim of the 3P wave has been Britain, which has yet to recover from the carnival of populism, polarisation and post-truth that gave rise to Brexit. Since then, not one but both of its major parties have fallen prey to populist leaders. And while the left-wing populism of Jeremy Corbyn atop the Labour party proved ineffectual and short-lived, a serial fantasist has installed himself solidly in 10 Downing Street. By sidestepping key guardrails against abuse, such as the longstanding norm that a minister who lies to parliament must resign, Boris Johnson is putting Britain’s democracy under a level of stress it has not known before, with new laws restricting the ability to protest showing that even the mother of parliaments is not immune to autocratic tendencies.

But the danger to democracy is most alarming in the East, with Hungary’s Viktor Orbán plainly the most successful of the region’s 3P autocrats. His gradualist approach to stripping away democratic safeguards has flummoxed Brussels for years, laying bare the European Commission’s relatively weak hand when it comes to protecting the bloc’s democracies from 3P assault.

Elsewhere, aspiring autocrats have shown it is possible to use 3P techniques to destabilise a democracy even without taking power. Negotiations to form governments take longer and longer because the rising share of the vote going to 3P movements leaves fewer seats in the hands of more and more ideologically disparate “normal” parties. In France this past April a shocking 58% of the first-round presidential vote went to extremist parties, all of them populist, some of them devoted followers of the 3P framework. In Spain, a far left that cut its ideological teeth advising Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez shares the cabinet with a more moderate left that is learning its worst vices, stacking the courts and stealthily undermining democratic norms. These days, it’s the countries that elect normal leaders over a main competitor who is also in the mainstream – Portugal, Denmark – that have become the oddity.

After the original Rip Van Winkle – the character from Washington Irving’s 1819 story – awakens from his long nap, he is asked whom he voted for in the presidential election. Having slept through the American Revolution, he cannot understand the question. For some years, I have struggled with the sense that, like him, too many of us have slept through a revolution – the 3P revolution. The hardest part about chronicling the rise of revanchist, often stealthy authoritarianism has been convincing people about how serious the threat was. I wondered how big an event it would take for the stakes to become clear to people.

Now we know. It took Putin to sound the bell that woke us all. He is uniquely dangerous, but he is not unique: he is only the most extreme example of the dangers inherent in this new breed of autocrat. He shows perfectly the way they hide their hand until they have enough power to wield it without limits. Then they’re freed to do their worst. And as Ukrainians know only too well, that can be very bad indeed.

The good news is that Europe has awoken not just to the threat, but to its own power. The EU awoke from its nap to realise what it has become: a superpower that did not know it was one. The Ukraine crisis, coming on the heels of Covid-19, has shown that the EU can take big, bold decisions quickly, when necessary, and wield its own power in defence of its values. The strength of the pushback Russia has experienced is heartening, as is the ongoing unity shown by its members. Nato, too, has shown that in the global conflict between unchecked autocracy and liberal democracy, the autocrats face a capable, mobilised and united opponent.

We will need that fighting spirit for the trials still ahead.

Moisés Naím is a Venezuelan journalist and best-selling author of The End of Power. He is also chief international columnist for El País in Spain. His new book, The Revenge of Power is out now.