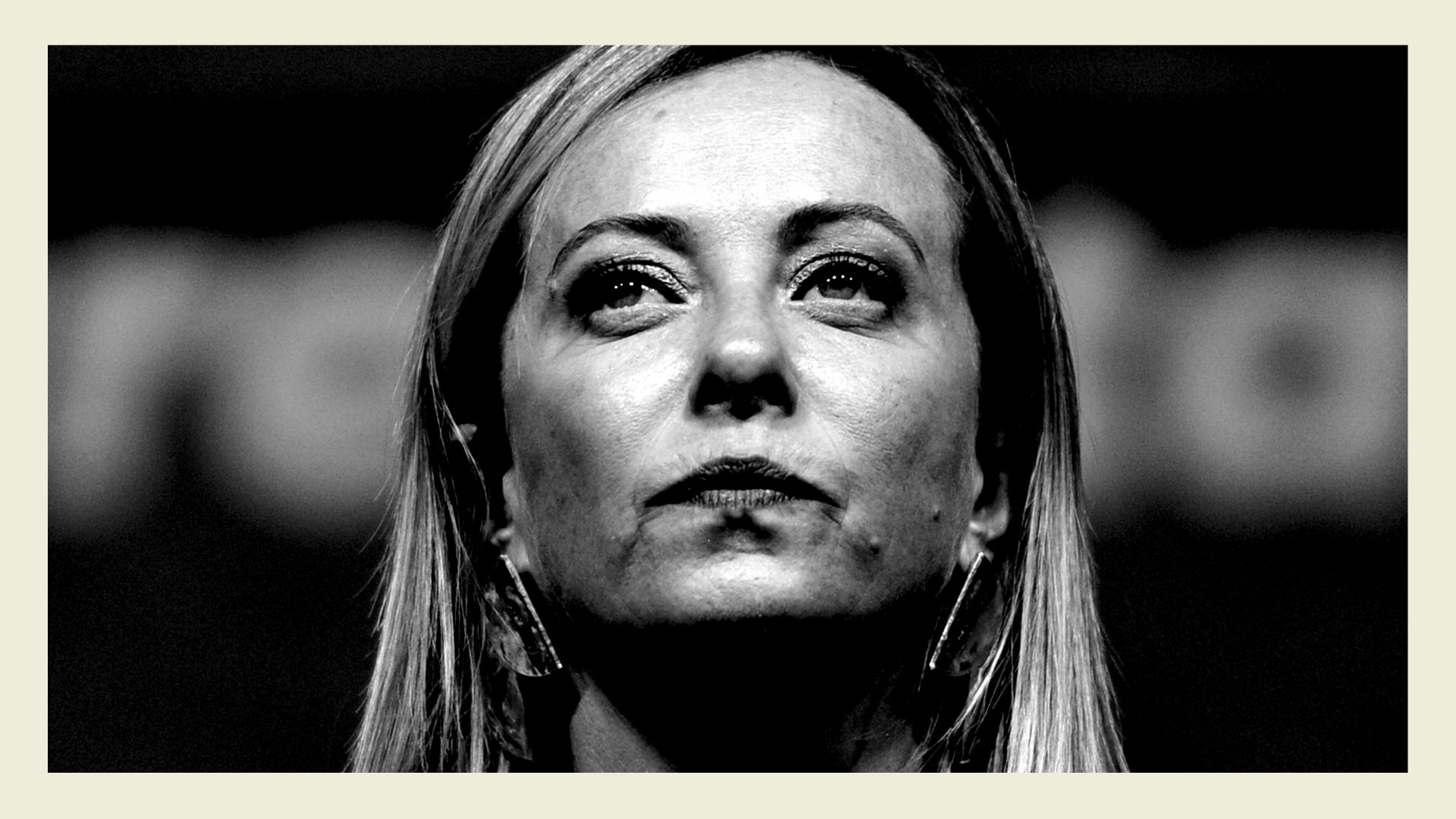

A year ago many pundits feared that Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni’s government would turn out to be a radical one. This was not just because of her party’s roots in the extreme right but also because she came to office promising big change.

A year in, Meloni has certainly not refrained from igniting culture wars. The bitter row over adoption rights for same-sex couples is a case in point. However, in other respects this government’s term has so far been much less eventful than expected. The need to project a certain image to international partners and the lack of fiscal wriggle room at home have seen her attempt to move away from her image as an extreme right-winger.

As far as foreign affairs and security matters are concerned, Meloni’s government has been treading the same path as its predecessor – the administration led by Mario Draghi. Meloni has stuck to a firmly pro-US and pro-Nato line, whether concerning Ukraine or the conflict between Israel and Hamas.

Sooner or later (and generally sooner), every post-war Italian government has reached the same conclusion that the country’s interests are best served by keeping close to the US and Nato, as well as remaining “at the heart of Europe”. In this sense, Meloni’s executive is no exception.

Meloni has worked to reassure her American allies of her credentials as a “moderate”. And, closer to home, she has cultivated a friendly relationship with Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the EU Commission. It’s a position that makes good financial sense since Italy is the recipient of the largest share of the EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund NextGenerationEU.

Politically, Meloni also needs to keep the commission onside if there is ever to be any hope that the EU will take on a greater role in managing migration and asylum-seeking at its southern border. In other words, Italy simply cannot afford a conflictual relationship with EU institutions right now, and Meloni understands this.

And then there are the international financial markets. Being seen as an irresponsible and extremist leader carries with it real risks for the prime minister of a country that relies heavily on foreign investors to help service an overall debt burden of over 140% of GDP. Memories of a previous right-wing government losing its parliamentary majority in 2011 due to considerable financial turmoil are still fresh in Italy. Meloni’s first experience of an executive role (as youth minister) was as a member of that government – which was led by one Silvio Berlusconi – so she is not likely to have forgotten either.

On a collision course?

However, Meloni’s apparent prudence and restraint are at odds with the promises she made to voters ahead of her election, potentially putting her on a collision course with her own supporter base.

She had pledged, for example, to set up a “naval blockade” to repel the boats carrying would-be migrants and asylum seekers who travel to Italy from northern Africa. This was replaced with a deal committing the EU to effectively paying Tunisia to tighten its border to prevent departures in the first place. Now even this deal is no longer on the cards. Meanwhile, Meloni’s Ministry of the Interior reports that the number of arrivals by sea has almost doubled since 2022, and almost tripled since 2021.

Nor do things look any easier for Meloni on the economic front. Many of her voters were led to believe that her government was going to reverse a reform of the pension system implemented in 2011, and that they would be able to retire earlier. But Giancarlo Giorgetti, the finance minister, now says there will be no comprehensive reform of the pension system after all. On the contrary, he has warned that with overall expenditure on pensions predicted to rise by almost 8% in 2023, strict control of public spending has become essential instead.

Populist radical-right parties are increasingly parties of government across Europe. However, they are subject to the same external constraints as any other administration. In Italy’s case, the country’s government needs to show fiscal restraint in order to keep the financial markets happy, and it knows that a good relationship with the EU Commission is essential to its success.

However, given the extent and speed at which the promises made during the 2022 electoral campaign are now being shelved, Meloni’s government risks giving right-wing voters the impression of being all talk and no action. This poses a conundrum for Meloni. Given the levels of electoral volatility in Italy, the last thing she can afford to do is take her recently acquired supporters for granted.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Daniele Albertazzi, Professor of Politics and Co-Director of the Centre for Britain and Europe, University of Surrey