The solitary female figure in Gwen John’s The Convalescent has become inextricably linked with the artist, and is probably her best-known painting. But the sick woman’s frailty could not be further from the life of the painter, which was lived robustly and unconventionally, mostly outside her native Britain, and certainly to the full.

Possibly the only point at which the convalescent and the artist overlap is in their choice of reading material. One of a series of pictures with similar composition and on a similar theme, the woman in The Convalescent clutches a letter. You suspect that she may well have read it several times, absorbing its encouragement, trying to build herself back up again. In other pictures, the model holds a book. Both the theme of the letter and the book point the way into Gwen John’s singular life, which was bound up in literature as well as art.

Born into a cultured family in 1876 in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, but raised in nearby Tenby, Gwen John was one of four children, two of whom became artists. Her younger brother Augustus, named after their artistically talented mother Augusta, would become, at least until recently, the better-known of the two siblings. But many contemporaries thought more highly of Gwen, and today she is considered to have had more talent and more depth than her brother, who largely settled for society portraiture.

At Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, the first major exhibition for 20 years dedicated to the artist, illustrates her range and juxtaposes her works with those of artists with similar aims. There are student copies of earlier works, portraits of friends and, towards the end of her life, of nuns, interiors, landscapes and even hints at experiments in abstraction. But the image of the woman reading became very much her calling card.

Trained at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, which was both go-ahead and rigorous in its tuition, John continued her studies by heading in 1898 for Paris, then the crucible of all that was happening, and at great speed, in European art. There, James McNeill Whistler had opened a school named the Academie Carmen, named for the enterprising model who ran the establishment. Men and women were taught separately – and the men were soon jettisoned for being more interested in basking in the great man’s glow than in working. Whistler found his female students more conscientious, and his encouragement of Gwen John had a career-long effect on her painting.

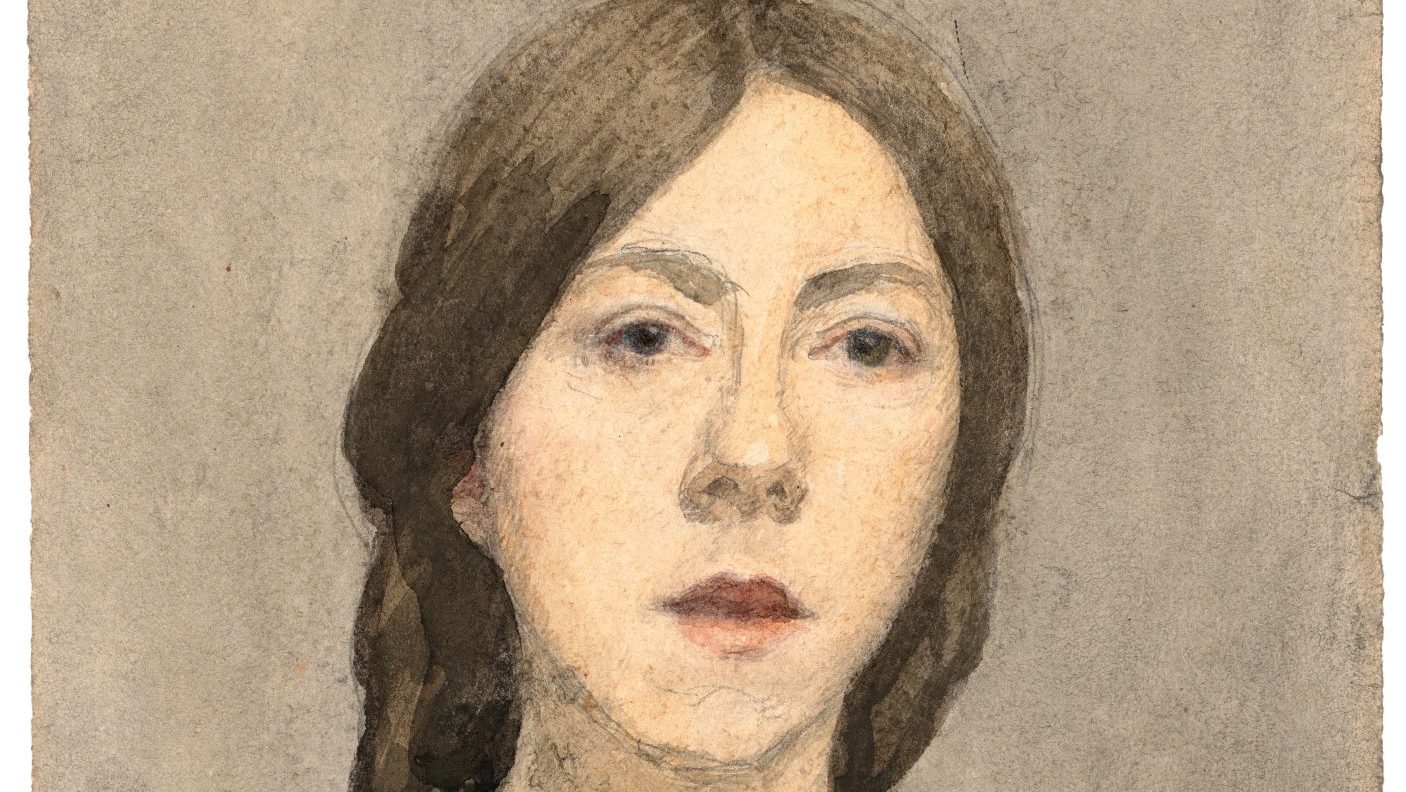

From him, she learned to determine the tones of her painting before putting brush to canvas. In consequence, she has a very recognisable palette, the dusky browns, greys, blues and pinks later lifted by the addition of chalk dust that renders the finish simultaneously arid and airy.

In Paris, she rubbed shoulders with the young lions of art, including Picasso, and saw the latest radical developments in art at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. She didn’t think much of Matisse, considering his work to be “far, far behind”, but was impressed by the Futurists, the short-lived group who would attempt to abandon tradition and inject movement into their paintings and sculpture. For an artist distinguished by the stillness and classicism of her own work, this interest indicates a broader mind than her painting suggests.

She enjoyed spending, especially in the Bon Marché department store, where she picked up fabric and trimmings for her outfits, and made ends meet by life modelling. She was very aware of her body, and her own nude self-portrait is matter-of-fact.

With no qualms about posing nude, she would soon be posing for Auguste Rodin, and was the model for one of the best-known works today in the Musée Rodin, his 1905 monument to Whistler, dubbed Whistler’s Muse. With one bent leg hoisted high in front of the other, despite the explicit nature of the pose, as the life model for a work based on a Venus de Milo sculpture in Rodin’s collection, John was being immortalised at a very early age.

Rodin was a towering figure in the Paris art scene, attracting artists and writers into his circle, among them the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Gwen John had pressed hard to model for Rodin after a first visit to his studios in 1904, and was eager not to lose his interest, assuring him that she could hold awkward poses for his dynamic sculptures and making light of discomfort. “Je vais vous donner des poses extraordinaire aussi bien que les poses classiques, car je suis souple” (“I’ll do extraordinary poses for you as well as classical ones because I am supple,” she wrote.

A photograph survives of her sitting for Rodin, legs twisted one way, head and shoulders the other, pale-skinned but with a suntanned face. She loved to walk, and clearly cared nothing for a fashionably fair complexion.

The sculptor and model began an affair that was partly fuelled by an extraordinary correspondence written by John, in answer to Rodin’s request for letters, but in the guise of “Marie”, who was confiding in her sister “Julie”. In them John wrote candidly and erotically about pleasing her “Maître” (Rodin himself), recalling with relish physical acts, including a threesome with his wife Hilde Flodin, and describing sexual fantasies. She is as far removed from the limp convalescent as it is possible to be. The letters were partly modelled on the epistolary novels of early fiction writers such as Samuel Richardson, whose Pamela she had read, and whose 1748 novel Clarissa Rodin urged her to try.

Alicia Foster, curator of the exhibition, Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris and author of an accompanying book, points out that it is rare and extremely fortunate to have insight into an artist’s personal library, thanks to 80 or so of John’s own volumes archived at the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth. Her love of Russian literature began during her time at the Slade, when she acquired a copy of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, in French. She later added stories by Chekhov, Turgenev and Gorky, also in French.

Her copy of Zola’s La Terre, published in 1887, a violent story set among the rural poor, is dated 1888: she kept up with new writing. Other books are missing, including a copy of Rilke’s poetry given to her by the poet himself.

She also collected books of art criticism and art history. One on Cézanne was lent to a friend, and is missing. But there are volumes on Holbein and Van Gogh. This respect for earlier artists is manifest in a painstaking copy of Gabriel Metsu’s The Duet, which she would have seen in the National Gallery, and of a drawing by Raphael, formerly attributed to Michaelangelo.

She loved Dutch paintings of interiors and wrote to Rodin that she wanted her work to be “comme les tableaux Hollandaises en sujet” (“like Dutch paintings in subject”). She became associated and exhibited with other painters of interiors, notably Pierre Bonnard and Eduoard Vuillard, while largely resisting the ornamentation of their domestic scenes.

But hers was not a snug world of carpets and cushions. She could be dismissive, even cruel, exhibiting sometimes strange allegiances. When Maud Gonne, political activist and muse of poet WB Yeats, was arrested for “sedition” in Paris, in 1923, John commented: “Isn’t she silly?” But when the controversial Lord Kitchener died, notwithstanding his Boer war atrocities, she declared herself “saddened”.

This ruthlessness was manifest early in her, encouraging her friend since the Slade, Dorelia McNeill, to leave another artist lover and join Augustus in a ménage à trois with his wife Ida Nettleship, another Slade contemporary. “When you leave him you will perhaps make a great character out of him,” she wrote. “I am sorry for people who suffer but that is how we learn all we know nearly.”

Converting to Roman Catholicism in 1913, she became close to the nuns at the convent in her home in Meudon, outside Paris. Six portraits of the order’s founder, Mère Poussepin, of which three are on loan to Pallant House, were taken from a drawing on a tiny prayer card.

In her 50s, John continued to walk great distances, as she always had, often at night. Some of her finest paintings show subjects in low light – interiors with subdued colours, indistinct street scenes and dark landscapes.

By now she had staged exhibitions in Europe and the US, been promoted by an important American collector, and been praised by the future director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, for pictures now in the Tate collection which “by their subtlety and colour make the work of her brother seem flashy and awkward”. But she would not rest on her laurels. She wrote in 1936 of enrolling at the academy of Cubist André Lhote, and tiny repeated drawings from this decade show her simplifying the outlines of two girls, suggesting that she might have edged nearer to abstraction,

Any such intentions were overtaken by ill health. Turning down a trip to Italy, she did venture towards Dieppe, where she collapsed and died, aged 63. Her body of work has perpetuated the impression of the artist as a shrinking violet. As this book and exhibition shows, nothing could have been further from the truth.

Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris is at Pallant House Gallery until October 8, and at The Holburne Museum, Bath, from October 21, 2023, to April 14, 2024. Alicia Foster’s book of the same name is published by Thames and Hudson (£30)