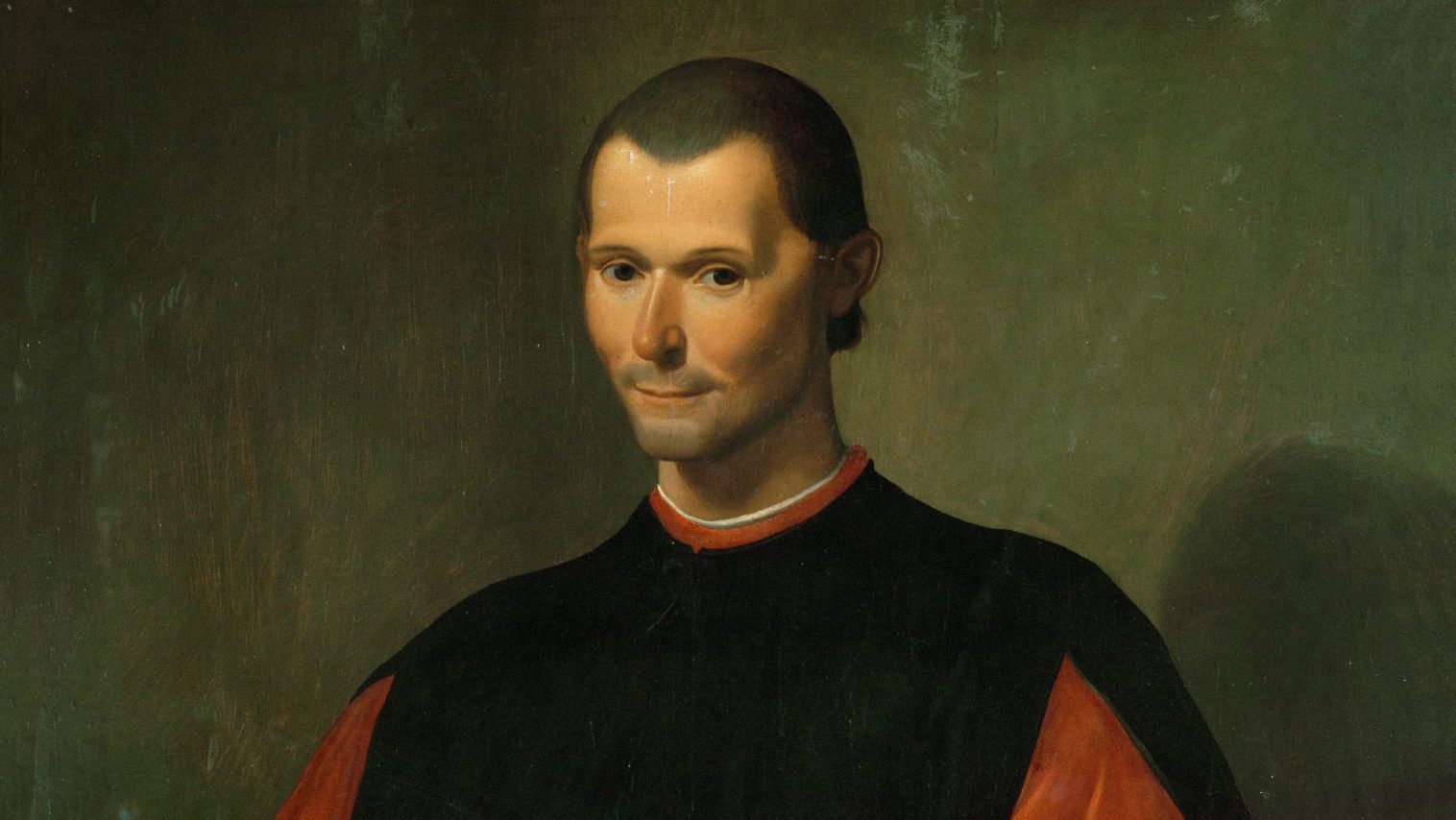

A 1532 first edition of Machiavelli’s The Prince has just come on the market. To the astonishment of antiquarian book dealers, this guide to the dark arts of statecraft comes with an estimated price tag of £300,000.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469 –1527) was a diplomat in Renaissance Florence when his city was the centre of the world in trade, art and intrigue. But a change in the political weather swept the Medici family into power and Machiavelli into outer darkness. To while away the time until his hoped-for return to influence, he composed a treatise on how to get ahead at court.

It was notable for being written in the tongue of the Florentine streets rather than in Latin, and for its mordantly undeceived voice. Among other brutally perceptive remarks, Machiavelli famously wrote, “It is much safer to be feared than loved because… love is preserved by the link of obligation which, owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity for their advantage; but fear preserves you by a dread of punishment which never fails.”

Machiavelli wrote The Prince in 1513, but it was only published after his death. Perhaps a copy crossed the Channel and fell into the lap of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s cold-eyed fixer. You could barely slip an executioner’s blade between the two men in terms of their outlook. Here’s Machiavelli: “If an injury has to be done to a man it should be so severe that his vengeance need not be feared.” And this is Cromwell, at least according to the BBC adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall: “When negotiation and compromise fail, your only course is to destroy your enemy before they wake in the morning, heavy axe in your hand.”

Machiavelli had learned from the best (or worst). He was an eyewitness to the unblushing machinations of Cesare Borgia, whose family name has become a byword for cruelty. Machiavelli observed Borgia in action as an envoy for the Papal States. He once invited his enemies to Senigallia with gifts and promises of friendship, only to have them all bumped off.

First editions of Machiavelli’s masterpiece are vanishingly hard to come by: the auctioneers Sotheby’s say that only 11 copies were known before the present volume came into their hands, only five of which are outside Italy. Their book was once in the collection of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, probably until the mid-19th century. Later, it belonged to an American insurance tycoon named Henry Wheelwright Marsh (1860-1943), an Anglophile who spent his summers renting grand billets for himself like Knebworth and Warwick Castle.

Sotheby’s notes that an early reader scribbled a pair of brackets around a passage in Chapter 18, “a section of the text with some of The Prince’s most strikingly modern pronouncements about the necessity for a savvy politician to manipulate the gulf between appearances and reality to his own ends,” according to the catalogue. “It is intriguing to find this subtle evidence of an individual centuries ago grappling with some of the central issues at stake in Machiavelli’s radical endorsement of realpolitik, questions which still animate discourse in today’s post-truth world.”

It is remarkable to consider that the word “Machiavellian” could work as a matter-of-fact description of politics today – that a little primer written 500 years ago could still describe the fundamental forces that shape our modern world.

A first edition copy of The Prince by Machiavelli is part of Sotheby’s Books and Manuscripts auction, open to bids until December 12

Stephen Smith is a journalist and broadcaster