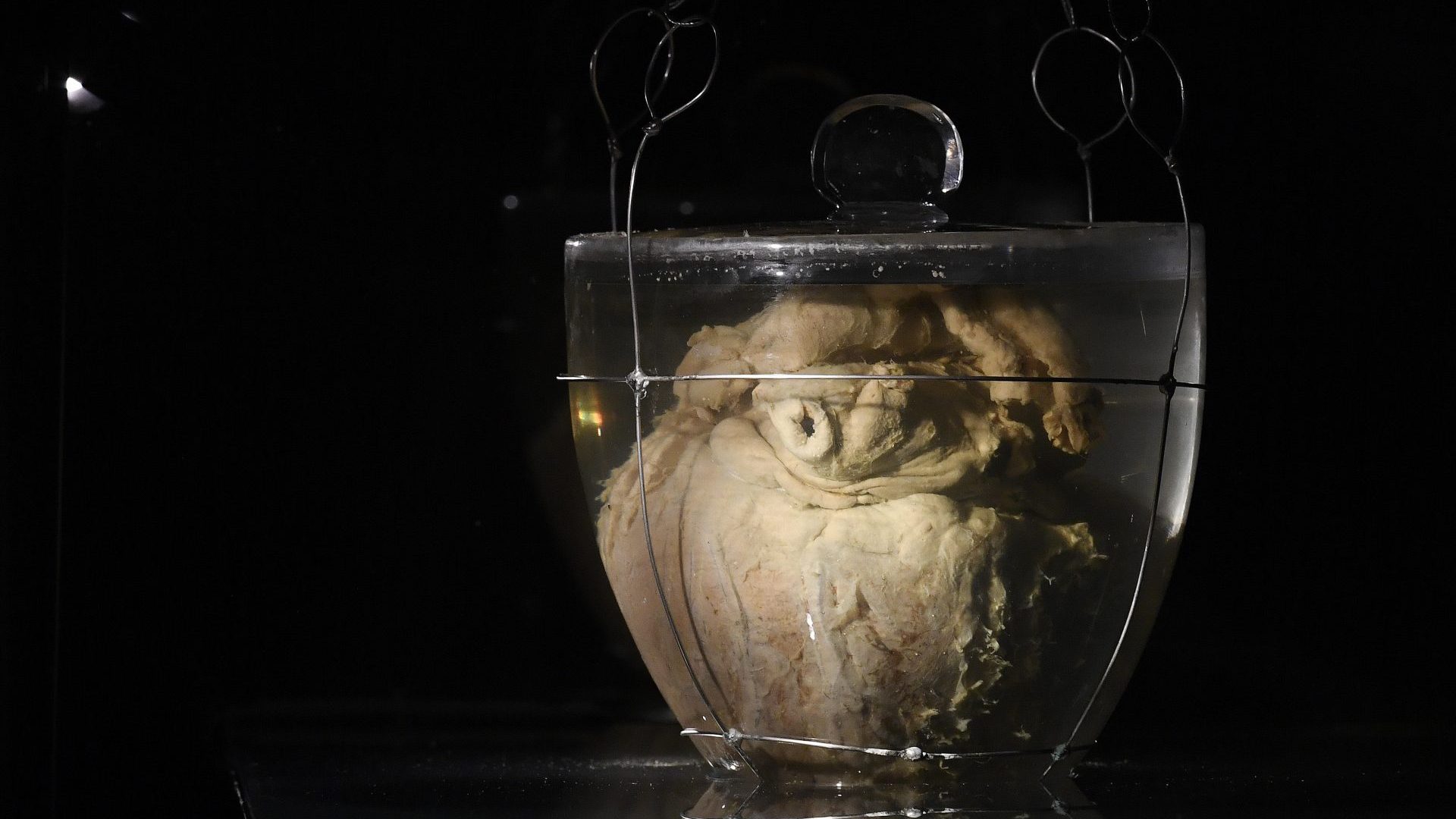

Last August, over the course of two days, more than 6,000 locals as well as tourists – many of them from Brazil – queued at the Church of Our Lady of Lapa in the northern Portuguese city of Porto. They were waiting to get sight of an embalmed heart, held in a glass flask.

The organ belonged to Dom Pedro I, nicknamed “the Liberator”, the Portuguese monarch who became the founder and first ruler of an independent Brazil. As Emperor of Brazil, Pedro put down rebellions in his army, defeated regional uprisings and even sailed to Portugal to fight against his own brother, before dying, aged 35, with a reputation as a champion of liberal values.

Since Pedro’s death in 1834, his preserved heart has been residing in private – and in formaldehyde – behind an inscribed marble slab in a Porto church. To mark the 200th anniversary of Brazil attaining its freedom, it was brought out of storage and briefly put on show in Portugal, before being flown 4,500 miles across the Atlantic to Brazil, where it was displayed in Brasília, the nation’s capital.

During the trip it was accompanied by the mayor of Porto as its official custodian, as well as by aides carrying a spare flask and emergency supplies of formaldehyde, in case of an accident.

Pedro, born in 1798 into the House of Braganza, was short-tempered, hyperactive and as a teenager had been known to wear a disguise and visit the dingiest drinking holes in Rio. And yet he was an unusually enlightened individual for his time. Having received little formal guidance on the art of political rule, he had read and absorbed the writing of liberal thinkers including Voltaire and Burke, a grounding that put him in tune with the emerging political and social ideas of the time.

In 1820, the army in Portugal took over the country and introduced a parliamentary system. This set off a wave of political disruption that spread across the Atlantic to the Brazilian army, whose leaders took the lead from their Portuguese counterparts, and mutinied. On several occasions, Pedro negotiated personally with the rebels.

He was a surprisingly artful negotiator and succeeded in outmanoeuvring his opponents. Under the slogan “Independence or Death”, Pedro won over the Brazilians, and on September 7 1822, aged just 24, he declared Brazil free of Portuguese rule and himself its emperor, Pedro I.

In December that year, he was crowned in Rio. In 1826 his father, João VI of Portugal, died, at which point he also became Pedro IV of Portugal, but he swiftly abdicated that throne in favour of his young daughter, Maria II, in order that he could stay in Brazil.

In 1831, after an increase in political tensions, Pedro sacked his cabinet, which led to yet another mutiny by the Brazilian army. Pedro then gave up the Brazilian throne, leaving his son in charge, in order to return to his native Portugal to lead liberal forces against his absolutist brother, Miguel, who had usurped the throne and junked the new constitution.

Pedro’s hard-won victory, after a two-year siege in Porto, and his role in establishing liberal institutions in Brazil as well as Portugal, meant that he is admired by many on both sides of the Atlantic. Brazilian visitors to Lisbon can file through the bedroom where the former emperor died of tuberculosis in 1834, in the Palace of Queluz, where he had spent much of his childhood.

Pedro’s heart went to Porto soon after his death, fulfilling his wish that it be kept in the city where he fought his fiercest battle. His body was buried in Lisbon’s royal pantheon but, in 1972, for the 150th anniversary of Brazil’s independence, it was taken to São Paulo – also according to his wishes – to be interred at the Monument to Independence there.

It is unusual perhaps that the request for the return of Dom Pedro’s heart was made by the Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, whose views are anything but liberal. His opponents accused the far-right populist of trying to make political capital out of the beloved monarch in an election year.

And so, after being put on show in Porto, the heart was received with military honours in Brasília before being transported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The next day it was taken in a Rolls Royce to a ceremony with Bolsonaro at the presidential palace, as six military jets drew a heart and the words “Independence 200 years” in the sky above.

The relic was even presented to foreign diplomats in Brasília, before going on display at the ministry until the Independence Day ceremonies on September 7. Just as they had in Porto, some members of the public took selfies in front of the yellowing organ. It was a ghoulish sight.

The arrival of the heart was also attended by Portugal’s president, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, who finally had the pleasure of a 15-minute meeting with Bolsonaro after being snubbed by him earlier in the year.

The two leaders have endured a fractious relationship – just as in the time of Dom Pedro, relations between Brazil and the old country remain a source of tension. Traditionally, Brazil was a destination for Portuguese emigrants, particularly from the late 19th century, with a more recent uptick in the wake of the euro-zone debt crisis. But the flow has streamed into reverse, with Brazilians making up a significant proportion of the workforce here in key sectors such as tourism. With these growing economic and personal links, maintaining smooth diplomatic relations should be a priority, certainly for Portugal. But that proved a challenge with Bolsonaro in charge.

A diplomatic gulf opened up at a time when migration flows from Brazil to Portugal have been at record levels. Recent figures from Portugal’s National Statistical Institute (INE) show more than 200,000 Brazilian nationals resident in the country – far outstripping traditionally large communities from former colonies in Africa, even without counting the many thousands of people originally from Brazil but who have Portuguese or other EU nationality.

In July, de Sousa visited Brazil to mark the centenary of the first flight across the South Atlantic by the Portuguese airmen Gago Coutinho and Sacadura Cabral. Though he had been invited to lunch with Bolsonaro, the details of where and when they were to meet never materialised. Already in Brazil, de Sousa repeatedly told reporters covering his visit that he was still awaiting confirmation of how the bilateral meeting was to take place. Bolsonaro eventually made it known – through the media – that he was “too busy” to receive the visitor. But it was clear to all concerned that he was angered by the fact that the Portuguese leader was also meeting Lula da Silva, Bolsonaro’s presidential rival, who went on to win the Brazilian presidential election.

The heart was flown back to Porto on September 9. Having won the election, da Silva made a point of visiting Portugal for talks with de Sousa, a conservative, and his socialist prime minister, António Costa. His aim was to repair ties that had been strained by Bolsanaro during four years in power in which not a single bilateral summit with Portugal took place.

The inauguration of Lula da Silva on New Year’s Day will be greeted with relief by many Portuguese officials, who make no effort to hide this. The 80,000 Brazilian voters who are officially registered as living in Portugal mostly shunned Bolsonaro this time, an outcome that reversed the previous Portuguese vote in the 2018 Brazil elections.

“Portugal is a brother country and an important partner for Brazil in Europe,” Lula tweeted, pledging to “resume our discussions in the best interests of our two countries.”

It is a sentiment of which the late Pedro I would have approved.

Alison Roberts covers Portugal for BBC News and others