I like to think I’m generally a positive kind of guy. Certainly when it comes to reading and talking about books I like to wear my hat at a jaunty angle on the side of my head and keep a rainbow draped around my shoulders as much as I can. There is much to be positive about in the world of books, after all.

The publishing industry in this country is far from perfect, but it is generally in rude health. To wander into a bookshop and find it busy with people browsing the shelves, picking up books from tables and flipping them over to read the blurbs, and making their way to the till looking excited by their new purchases is a scene that fills me with joy, almost as much as the thrill of opening a new book myself, breathing in the tang of fresh ink and paper.

Yes, authors could do with a better deal and we need a system that encourages – and more importantly funds – people from outside the world of privilege into authorship, but we are enjoying a time when more great books are being written than ever before and are being sold between covers that confirm this as a golden age of book design.

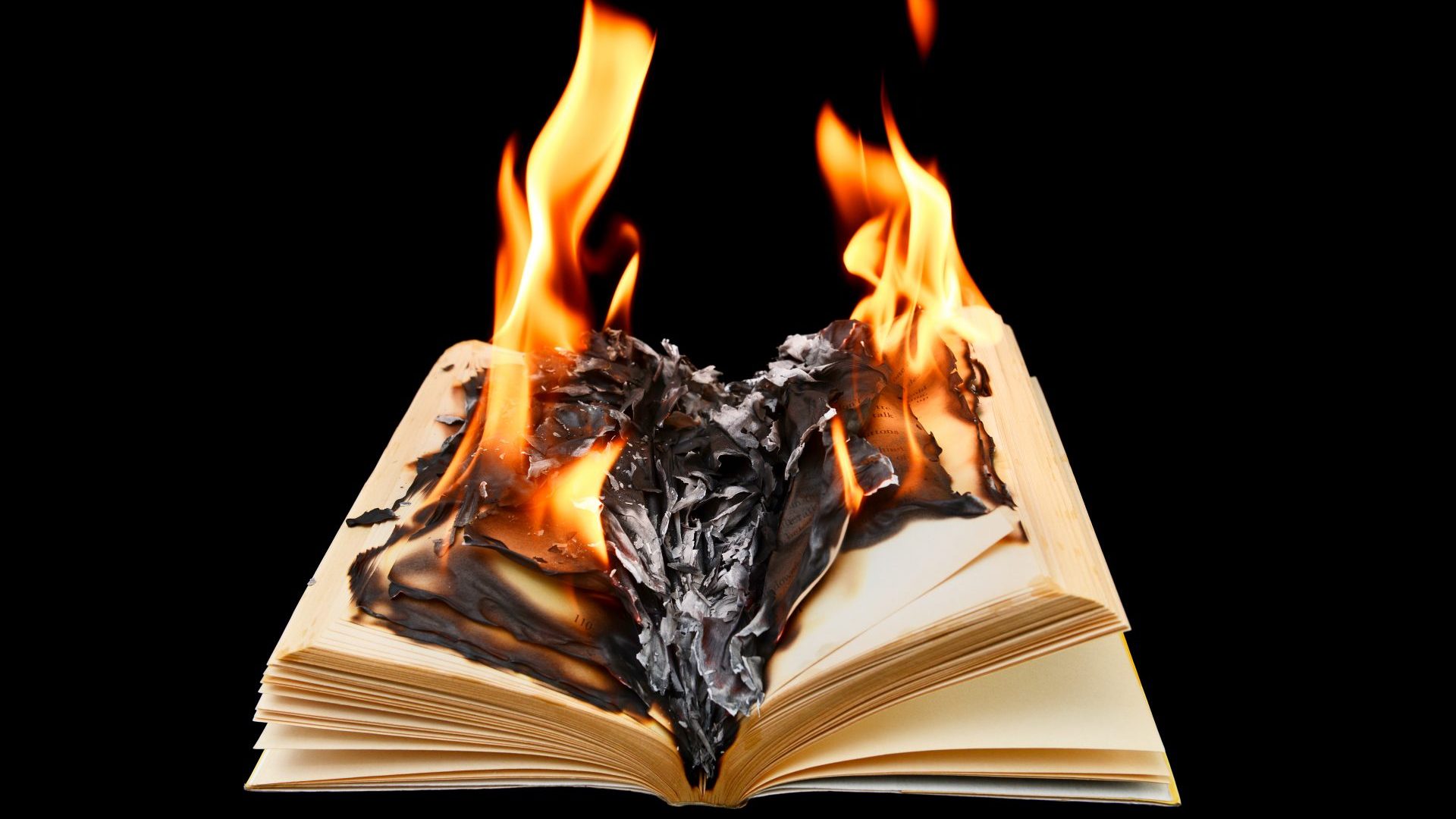

Yet lapsing into a satisfied reverie would be to ignore some of the threats currently facing the world of books. I was snapped out of it myself last week by two pieces of news from the wider world of literature.

First, the bestselling Russian author Boris Akunin was declared by Russia’s foreign ministry to be a “foreign agent” due to his continued vocal opposition to the invasion of Ukraine. He stood accused of spreading false and negative information about Russia and giving financial aid to the Ukrainian armed forces.

Then I learned that the book-banning epidemic in Florida has now become so ridiculous that among the 1,600 titles removed from schools in Escambia County because of their threat to children’s morals was… the dictionary. The actual dictionary.

I mean, if Kurt Vonnegut had put that into a book it would have been hilarious, but this is actually happening, right now, in the real world. Coupled with a thriller writer being declared a pariah for saying maybe his country shouldn’t be bombing and shooting its way into a neighbouring one, suddenly the world of books didn’t seem quite as rosy.

Boris Akunin is the pen name of 67-year-old Grigory Chkhartishvili, author of a string of hugely successful Russian historical detective novels, many of which feature his charismatic 19th-century detective Erast Fandorin. In 2000 Akunin was named Russia’s Writer of the Year, and he remains one of Russia’s biggest-selling writers. Which in a country that size is really saying something.

He is also, however, a long-term and vocal critic of Vladimir Putin.

As far back as 2010 Akunin was describing Russian history as a centuries-old conflict between what he called the “aristocracy” and the “arrestocracy”. By aristocracy he did not necessarily mean a nobility, rather the good guys, those who strive for idealistic goals, people who “changed their political slogans and platforms but the struggle remained the same, a struggle for human dignity, that benchmark indicator of a country’s level of civilisation”.

Ranged against this school of thought, according to Akunin, is the arrestocracy, regimes that assert power by silencing dissent and placing huge restrictions on personal and political freedoms. He traced a direct line between the Tsarist secret police, the Okhrana, to the entire methodology of the Putin regime, devastated that the events of 1991 and the fall of communism had brought more tyranny when there had been such hope.

In 2013 he spoke at an opposition rally in Moscow – in those far-off innocent days when such things could happen – calling for Russian cultural figures to speak out in opposition to Putin’s authoritarianism.

“If locking people up becomes normal, no right-minded person can or should cooperate with the state,” he said. “It is that shameful thing known as collaboration… No decent person can cooperate with a police state. It is just not possible.”

In December last year Akunin was designated an “extremist and terrorist” by the Russian state and was under criminal investigation for “justifying terrorism and publicly spreading fake information” about the Russian military.

“Terrorists declared me a terrorist,” he chuckled in response.

That designation came after the leading Russian publishing house, AST, announced that it would no longer distribute books by Akunin or his fellow writer Dmitry Bykov as a result of their “public statements” in support of Ukraine.

Both men have always publicly opposed the invasion. On the day Putin’s tanks rolled into Ukraine, Akunin wrote on social media that Putin was a “psychologically deranged dictator” who had been “very methodically killing all the branches of democracy”.

What prompted official condemnation, however, was the December broadcast of recordings in which both writers expressed their support for Ukraine after being duped by a pair of Putin-backing prank callers.

As well as AST, the bookselling chains Chitay-Gorod and Bukvoed withdrew all copies of Akunin’s books from sale. The Russian literary journal, Novy Mir, removed all references to the bestselling author from its website. Andrey Gurulyov, a deputy in the Russian State Duma, even appeared to call for Akunin’s death. “He should not exist in this world,” he said. “This is probably the only way our country will survive.”

Akunin, who divides his time between Britain, France and Spain after leaving Russia in response to the 2014 invasion of Crimea, reacted stoically. “A seemingly minor event – the banning of books, the declaration of a writer as a terrorist – is actually an important milestone,” he said. “Books have not been banned in Russia since Soviet times. Writers have not been accused of terrorism since the Great Terror.”

In Florida, meanwhile, right-wing organisations have been enthusiastically withdrawing a range of titles from school curriculums and libraries for many months now. So enthusiastically, in fact, that the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the standard US reference work equivalent to the Oxford English Dictionary here, has been added to the pile of around 1,600 titles removed from schools in Escambia County on the grounds of its – get this – “sexual content”.

Similarly condemned works include The World Almanac and Book of Facts, the Guinness Book of Records, biographies of Beyoncé and Oprah Winfrey, The Teen Vogue Handbook: An Insider’s Guide to Careers in Fashion and Anne Frank’s diary. As well as the Merriam-Webster, seven other dictionaries and five encyclopedias make the list.

“Dictionaries have always held an important place in our schools,” responded Merriam-Webster’s president, Greg Barlow, admirably masking his bewilderment. “They help all of us, including students of all ages, expand our knowledge, learn the value of words, and most importantly teach us how to communicate with each other.”

The Escambia County school board primly pointed out that the books have not been banned, merely removed for further review. By what standards you “review” a dictionary for improper content isn’t clear, but it’s unlikely to extend beyond “finding some words weird people don’t like”.

The book world and authors are fighting back. Bestselling novelist Ann Patchett, who runs a bookshop in Nashville, discovered recently that two of her novels had been banned by the Orange County school system in Florida including her debut, The Patron Saint of Liars, set in a home for unmarried mothers.

“We don’t get to see the girls having sex,” she said in a video response on Instagram that skewered the ridiculous hypocrisy of the situation. “They just show up pregnant at a home for unwed mothers because they choose not to have an abortion. They have the baby and give the baby up for adoption just like they tell us to in the state of Florida.”

Fellow novelist Lauren Groff is taking her response to the book bans a step further by opening Lynx, a bookshop in Gainesville, Florida, specialising in the writers and books that have incurred the wrath of the state’s self-appointed moral guardians.

“The impetus for creating this space was feeling as though we were a little bit under a sneak attack by some forces who want to limit our expression and our freedom to read the books that we want to read,” she said in a video statement, “to learn the history of the United States even if it makes us feel bad.”

The shop is due to open its doors in April, and is currently running a successful crowdfunding initiative to which a number of household literary names have donated items and services.

“I see a bookstore as the beating heart of a town,” said Groff, who has lived in Gainesville with her husband for the past 16 years. “I would really, really love for this independent bookstore, in particular, to be a place that takes a stand for the ability of Floridians to have knowledge and understanding of the world we live in.”

Very different writers from opposite sides of the world, Groff and Akunin make unlikely neighbours in the literary trenches but both find themselves facing down crass threats and, for Akunin in particular, perilous dangers. A lot of guff gets spoken about the power of books and the positive influence of reading a range of opinions in a range of subjects, but that truth is never brought more sharply into focus than in incidents like these. To call it a battle against ignorance sounds patronising, but that is exactly, literally, what this is. The fight goes far beyond books, and is one the world cannot afford to lose.

“I’m no prophet,” said Akunin. “I’ve no idea how long such a repressive regime might last, but I know my history and I know how it will end. Any system that isn’t based on a dialogue with the public, that can’t maintain a consensual civic society, is doomed to fail. Modern history tells us that no other outcome is possible.”