The surprise is that we are still surprised. A seemingly eccentric outsider arrives on the political scene and either wins an election or comes close to doing so.

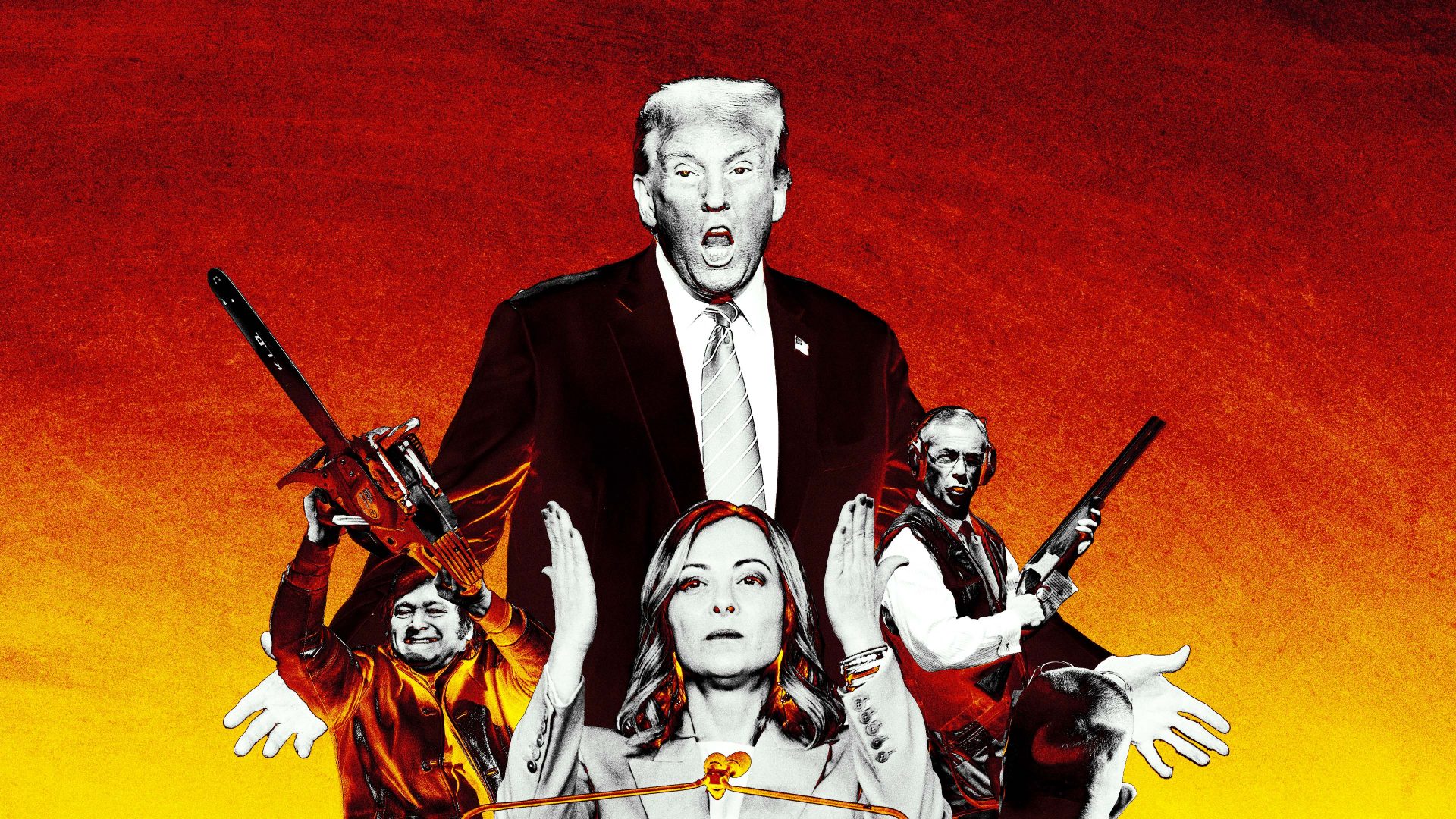

Donald Trump is back in the US, the most spectacular comeback in the history of presidential contests. Javier Milei makes waves in Argentina. In Romania, the apparent fringe candidate, Călin Georgescu, came close to victory before evidence of widespread interference – possibly from Russia – saw the entire election annulled.

Giorgia Meloni rules in Italy, having made a pitch as a right wing populist outsider even if she leads with a hint of pragmatism. In France, Marine Le Pen continues to be a player of significance, a force in bringing down the Barnier government. Meanwhile in the UK, Nigel Farage now sits as an MP, and is the British party leader with the closest relationship to Trump.

Farage’s prediction at the end of last year that Reform will have “hundreds of MPs” after the next election sent shivers of fear down the spines of Labour and Tory leaders. None mocked the swaggering claim.

In the era of the outsider, there is even speculation that Jeremy Clarkson might enter politics. He is qualified to do so. As a celebrity who can frame an accessible argument while showing disdain for the toiling elected politicians at Westminster, he meets the familiar criteria of success.

A pattern formed long ago. But that is precisely where there is now a big and ominous surprise.

The durability of the outsiders is jaw-dropping. They are not fleeting phenomena that soar and fall.

In 2016, I began to write a book, The Rise of the Outsiders, that was published the following year. The context then was striking. Trump won his first victory. In Spain, Portugal and Greece, left wing parties had emerged to shake up the political landscape.

In Germany, the far right AfD secured parliamentary representation as I was finishing the book in 2017. Two years earlier Le Pen’s party had made huge gains in local elections, coming first in six of France’s 13 regions.

As for the UK, a country with an undeserved reputation for stability, all hell was breaking loose. There was the astonishing rise of the SNP in Scotland, the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party, coming close to victory in the 2017 election, and Brexit in 2016 – a seismic break with the past, stirred by Farage, who was not then even an MP.

As I was writing, I was not wholly sure that the outsiders would last until the deadline for publication. When I began the book there was a widespread assumption that Hillary Clinton would beat Trump and that voters in the UK would support Remain.

Not only did the opposite happen then but outsiders flourish still, the same sort of anti-politics politicians and the familiar volatile economic background that propels them to the top. They may be superficial in their pitch, but their appeal is deep and lasting.

Indeed the superficiality is part of the appeal. Nearly a decade ago, celebrities were flourishing. Trump was the most prominent, the star of The Apprentice stressing that he had no association with the failed system in Washington DC.

The comedian Beppe Grillo and his Five-Star Movement literally lifted a middle finger to Italy’s political class by staging a national “fuck you” day. Above all, the outsiders were “anti-politics” as practised by mainstream parties.

Now Trump is back, still a celebrity and far removed from an orthodox politician. Milei was a former Rolling Stones tribute band member who looked, during his triumphant campaign, as different from a conventional politician as it is possible to look.

But the outsider does not have to be a celebrity to succeed. The key is to be distinctive, different from what has gone before, to be the personification of ill-defined “change”.

Economies are fragile and even when they are not, many voters feel worse off. The US economy is growing in ways that any other G7 country would die for, but food inflation is still high. Voters in the US presidential election felt worse off. Soaring inflation was an issue in Argentina when Milei won spectacularly. In Romania, the cost of living is high and the war in Ukraine is destabilising.

Everywhere, the movement of people in response to climate change, war and tyranny generates the second crisis of the global economy. The first was the global crash of 2008, the event above all others that triggered the rise of the outsider, when so many assumptions and orthodoxes were overturned while the bankers continued to flourish.

In an era of wild uncertainty and insecurity, the outsiders have answers or appear to do so. Their self-confidence is infectious.

When Trump declared that “tariff” was his favourite word in the English language, he made protectionism seem like a route towards paradise, one that would make America great again. He believes it too. There are no hesitant caveats based on anxious reviews of recent focus group findings.

When Milei denounced the hopelessness of the Argentinian state and pledged to create a smaller one driven by the dynamics of market economics, citing various freakish libertarian economists, there were no doubts or evasions. That is what he intended to do.

When Georgescu hailed the sovereignty of the Romanian people, he evoked images of a mythologised nostalgic past and a more secure future.

Policy details are pushed aside with the showman’s swagger. When Farage was asked by Mishal Husain on the BBC how he was going to close the borders, he had no clear answers.

Would he allow nurses to come? Yes, they could come. Doctors? Some could come. Care workers? Yes. You plan to process all these claims outside the UK? No… that would be totally impractical. But it’s on your website? Well… we’ll take it off.

None of this matters to a lot of voters. Farage has offered them a chance to join the “people’s revolt” and enough of them are thoughtlessly disillusioned to do so.

But thoughtlessness is only one part of the explanation. The failure of so-called mainstream parties to challenge the outsiders is another. They have failed in terms of language and ideological verve to counter the populists’ self-confidence and radical policies.

At a time of sweeping change they offer nervy, plodding incrementalism. Even when they are being ambitiously radical they appear to be fearfully cautious by deploying technocratic language.

In terms of language, increasingly important in the era of the ever-more limited attention span, Kamala Harris’ main slogan repeated as a motif in her rallies was “We’re not going back”. But a significant number of voters yearn for the past as they imagine it to be. They regard such a slogan as a threat.

When “take back control” became a winning slogan in the UK Brexit referendum, key figures on both sides recognised the word “back” was key. Some Brexit voters sought a return to an imagined past. Harris told her voters there was no going back. As for policy, at no point did Harris challenge Trump on the consequences of tariffs. He had a free ride on the economy, the issue that still decides elections.

In the UK, Keir Starmer has a weapon to target Farage in the failure of Brexit. He lacks the language and persuasive powers to do so. Instead, his apolitical approach to Brexit and other matters is a gift for Farage.

Starmer speaks of foundations, missions, milestones and making Brexit work. There is no accessible explanation as to why Brexit has failed or why the economy is close to stagnant after 14 years of Conservative rule as a starting point for why his government will take a different approach.

Starmer is indifferent to the crucial “Why?” question in politics. He is admirably interested in the “How?” question but that is not enough.

Farage wields the “Why?” question like a weapon. At its broadest (and he tends to stick with the broad) his pitch is: “I’ll tell you why they’ve all failed. They’re detached from the concerns of ordinary voters.”

Ironically, fearful technocratic leaders have never been more in touch. Starmer receives data from focus groups and opinion polls most days of the week. These findings can lead to a form of hesitant paralysis that creates more space for the outsiders.

In the era of globalisation, an unresolved debate about the role of the state fuels the outsiders. Most of the populists on the right are far removed from the small-state ideology that was prominent in the 1980s and 1990s.

Trump is a statist. His support for tariffs is a huge intervention in the market. His pledge to close the borders is another act of state muscularity.

Back to the mainstream and the likes of Starmer occasionally refer to an “active state”. But the reference is not developed. Biden was active too, borrowing billions in ways that stimulated economic growth. His record was taboo during the US election because Biden was part of the Democrats’ problem and had to be hidden away.

This is the challenge for mainstream parties, specifically those on the centre left. They need to show that the modern state can deliver for voters and work around the clock to ensure that the connection is made between what they are seeking to do and improvements in voters’ lives.

If they fail in either delivering or making that connection, outsiders will continue to flourish. None of us should be surprised if Jeremy Clarkson is next.

Steve Richards presents the Rock N Roll Politics podcast. The Rise of the Outsiders is published by Atlantic