When, on July 3 1973, at the Hammersmith Odeon in west London, David Bowie retired Ziggy Stardust, it was like a death in the family. For a generation of impressionable teenagers like me – I was 13, and considered Bowie to be the very closest thing to heaven I could imagine – watching the person you adored abdicate from your life was, well, almost like a bereavement.

It sounds silly. It even looks ridiculous now, reading what I’ve just written. But it was true. To a generation who had yet to lose their virginity, to lose someone so close to you was heartbreaking, and novel.

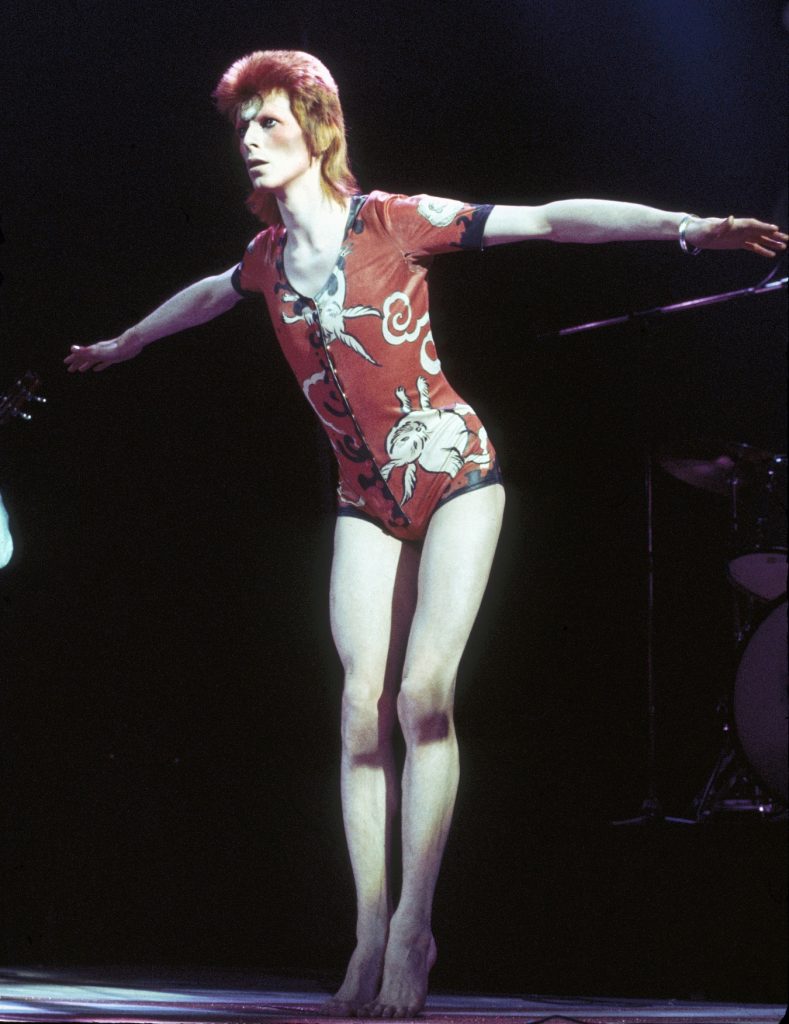

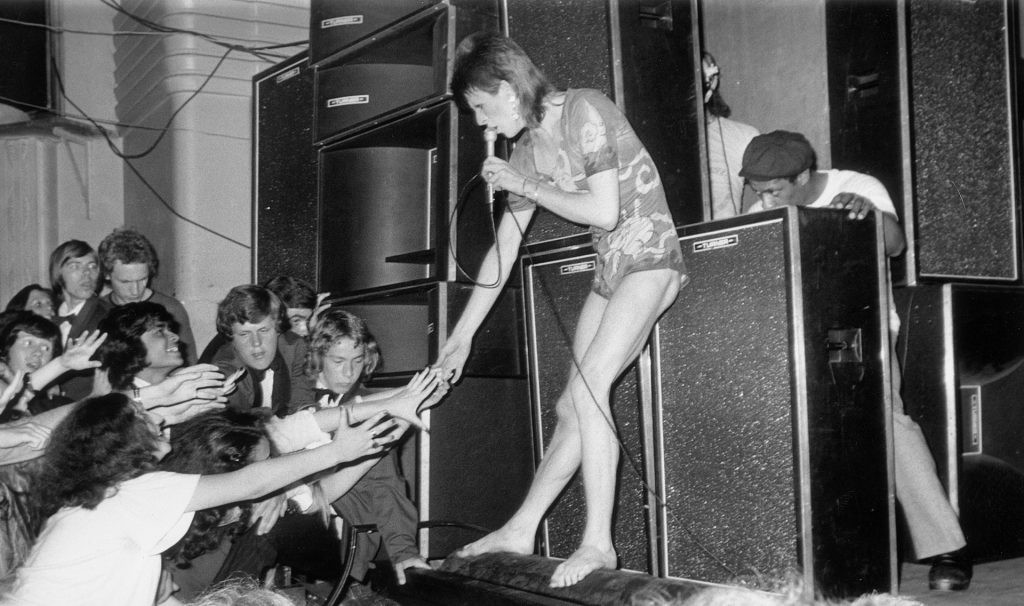

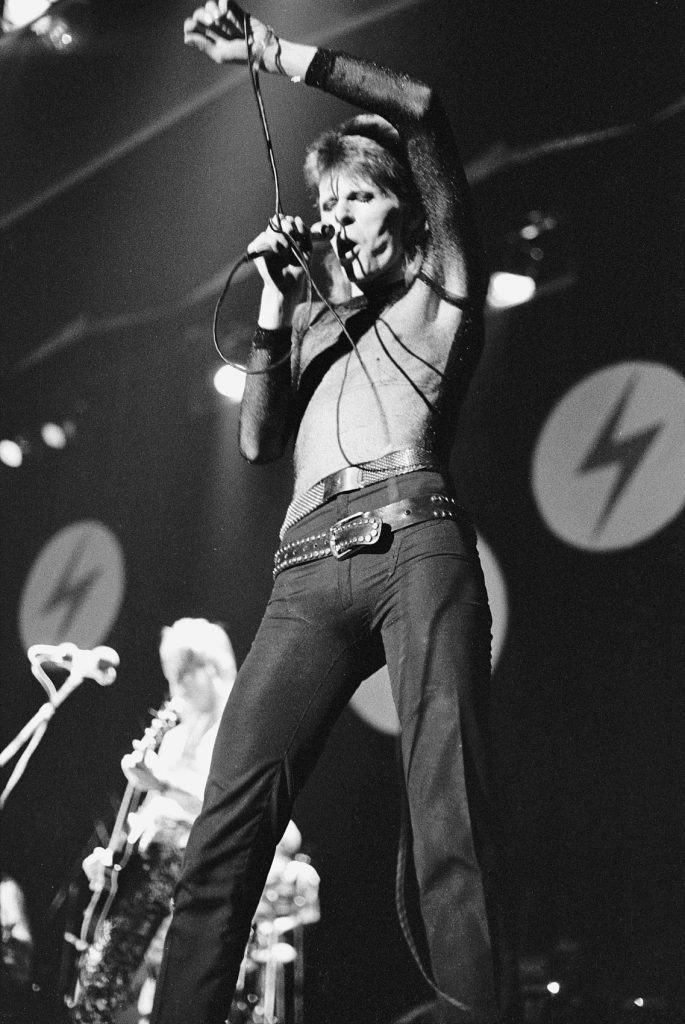

What had he done? With one song left of his triumphant sold-out Spiders from Mars concert at the famous Odeon, Bowie told the assembled multitudes that he was killing off his alter ego and retiring. The man who had electrified a nation of youths who had missed out on the Beatles, and who didn’t understand longhair music, was kissing us all farewell, presumably – we imagined, salaciously – crawling off to his Chelsea lair to have a threesome with his wife and a willing accomplice.

After striving to be successful for a decade, Bowie was killing off his golden goose. Having tried to make it as a folk singer, an R&B performer, a Mod, a folkie, and even a children’s entertainer, Ziggy Stardust had afforded him genuine success.

And now he was killing him off. What the hell was going on?

Well, Bowie was moving on, that’s what. And he was taking no one with him. At least no one you knew. No one he knew.

When he announced Ziggy’s retirement on stage that night, his band were shocked.

“We didn’t know anything about it beforehand. I was a bit, like, “What the hell’s he on about?” said his bassist, Trevor Bolder. “Woody [Woodmansey, Bowie’s drummer] thought about walking offstage before we did Rock’n’Roll Suicide. He told me later that if he’d known beforehand, he wouldn’t have done the gig. That’s why they didn’t tell us. They couldn’t take the risk we’d say “Up yours!” and walk.”

Bowie had had enough. “Ziggy was a monster, but he was my monster,” he once said to me. “My very own monster, ha!”

Ironically, as he closed the door on glam rock, another musical force – punk – was almost on his doorstep. In fact, given half a chance, they would have stolen the door.

After the Hammersmith Odeon gig, the future Sex Pistol Steve Jones – at the time a 17-year-old petty thief – decided he needed some new gear for the band he was starting. Sneaking by a snoring security guard who was sleeping in the fourth or fifth row, “catching flies” in his mouth, Jones slipped backstage and threw as much of the Spiders’ equipment as he could carry into his minivan: Trevor Bolder’s Sun bass amp, several cymbals and a little Electro-Voice microphone that still had a smudge of Bowie’s lipstick on it.

“I don’t recall feeling any compunction about nicking my idol’s gear, only the full-on excitement, especially when it was on the news on Capital Radio the next day,” said Jones. “It was my first bit of fame and I liked it. That’s why I’ve got some understanding of what’s going in the minds of these lunatics who go and shoot up a fucking school just to get their 15 minutes on the news. It’s that level of narcissism where you get excited because you’ve made your mark in the world.”

Nevertheless, this was not only one of Bowie’s most important concerts, it also soon became one of the most iconic pop performances of its time, a gig that now is easily as fetishised as Queen at Live Aid, the Sex Pistols at St Martin’s School of Art, or Kanye at Glastonbury.

And yet at the time, Bowie’s amateur dramatics were seen as that and only that: purely theatrical. The former NME writer Nick Kent says that at the time many critics thought Bowie was somehow inauthentic, while a New Yorker writer flown to see the Ziggy shows in London fretted that “Bowie doesn’t seem quite real.”

Which was precisely the reason we loved him so much. Here was artifice, here was delusion, but also here was something that we didn’t need to unpick. We liked it, enjoyed it, and weren’t all that bothered that a lot of what Bowie did felt somehow secondhand.

Oh to be that secondhand!

Anyway, in 1973, for the rest of the summer, each and every one of us felt like we had lost a member of the family.

And if truth be known, we somehow had.

Dylan Jones is the author of the best-selling oral history David Bowie: A Life (Windmill)