It always was a dream. We could care for everyone’s health from cradle to grave, through a service free at the point of need, funded from general taxation. It was a dream worth working for. Some people, however, disagreed. The market is supposed to provide services, they said. It’s “their NHS”, not ours. Much better, they said, to “go private”.

After years of struggle, the NHS’s current state is beginning to weaken the resolve of even the most committed dreamers. The NHS is not the envy of the world, the naysayers (rightly) argue. It’s time to get real, they say, and do things differently – details to follow, but definitely involving the market and the private sector.

The dream has become a nightmare. It needn’t be so, but it is. Before it’s too late, we need to ask a question rarely asked. Is the NHS’s imminent demise intentional? Has it in fact been long in the planning? Let’s look at the evidence.

First, there’s austerity, introduced in 2010. While the Labour Party descended into a leadership squabble, the Tories implanted in the public mind the notion that the financial crash of 2008-09 was the fault of the preceding Labour government. In fact, it was precipitated by high-risk financial activity in Wall St and the City, and Gordon Brown played a big role in resolving the ensuing crisis. But the Tories’ message got through, as did the message that the only response was to introduce austerity.

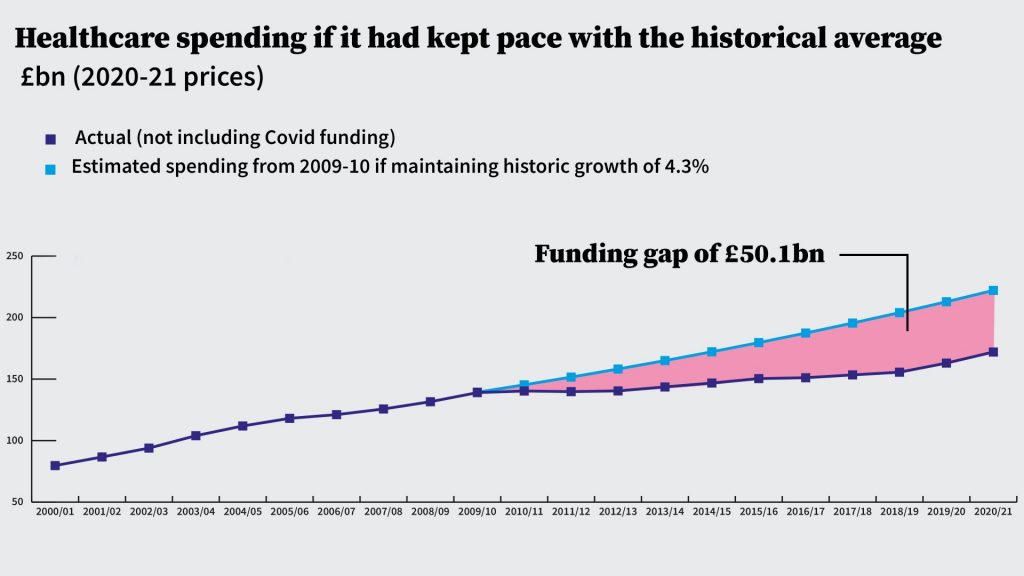

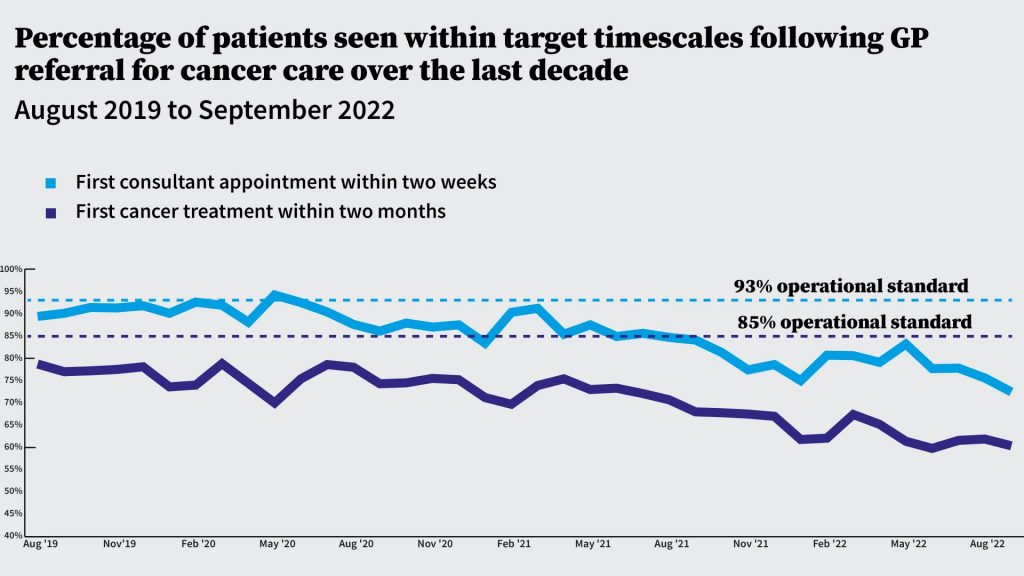

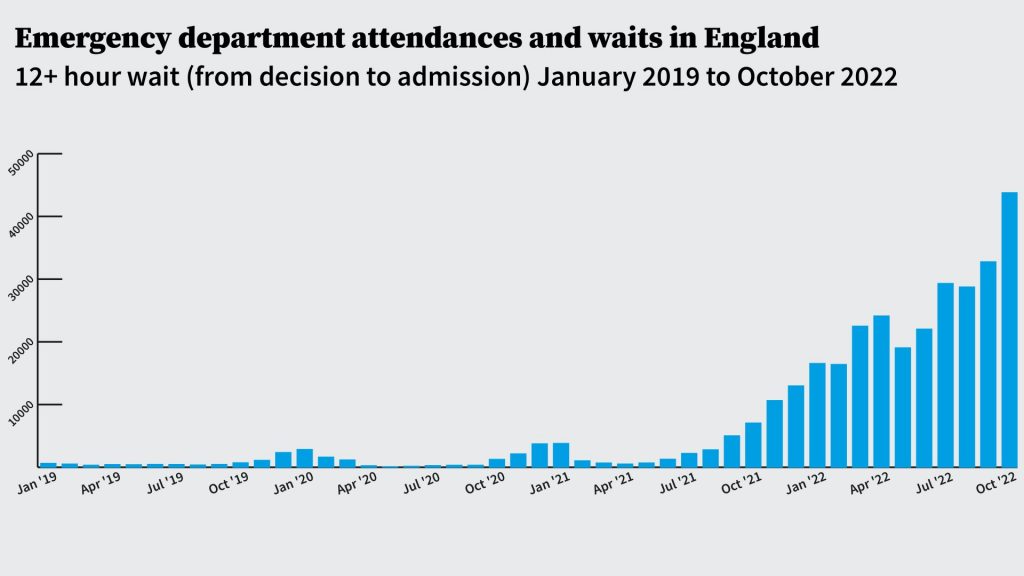

This decision to tighten government spending in the face of an economic downturn was not the only one available. It was a political decision – the necessary choice if the goal was to reduce the size of the state and withdraw the government as far as possible from its role of protecting the governed, save with a nod to those most in need. Austerity, as played out in the case of the NHS, starved it of resources, limiting the ability to train, pay and keep its staff. Clever economists line up to show how well the NHS has been funded using this or that model. People waiting to see their GP, or lying in ambulances for hours, or dying before their appointment for cancer treatment, provide the reality check.

The clue to what the NHS is about is in the name – the National Health Service. Over the decades, however, the focus has shifted inexorably to healthcare. Keeping the population healthy has been increasingly dismissed as not being the state’s or government’s business. Instead, it’s up to the individual and the family to remain fit and healthy – and if they do not, then blame them for their fecklessness.

The organisation concerned with health was Public Health England. Its budget and role have both atrophied, undermined by disapproving talk of the “nanny state”. Individuals should be entitled to choose what to do, the argument goes. The market will ensure they are healthy. But BOGOF, fast food, cheap booze and obese children suggest otherwise. Mental health problems are at epidemic levels, but the market can’t do much about it except produce drugs, so drugs are touted as the solution.

In my Reith Lectures of 1980, I argued that redefining the NHS as a Healthcare Service or even an Illness Service turns the spotlight on to hospitals. They, it is said, are the NHS’s future and consequently we need more of them – 40 more, according to one of our recent prime ministers. This is perverse in so many ways that it’s hard to know where to begin. The developers and builders will be rubbing their hands.

If health is the goal, building hospitals is an own goal. The NHS should be trying to keep people out of hospital. And, even if the mass production of hospitals were the right approach, where are the staff going to come from? We’ve sent many thousands packing as a consequence of Brexit. The shortage of personnel is further exacerbated by the failure to train enough people and, once trained, to encourage them to put up with deteriorating working conditions.

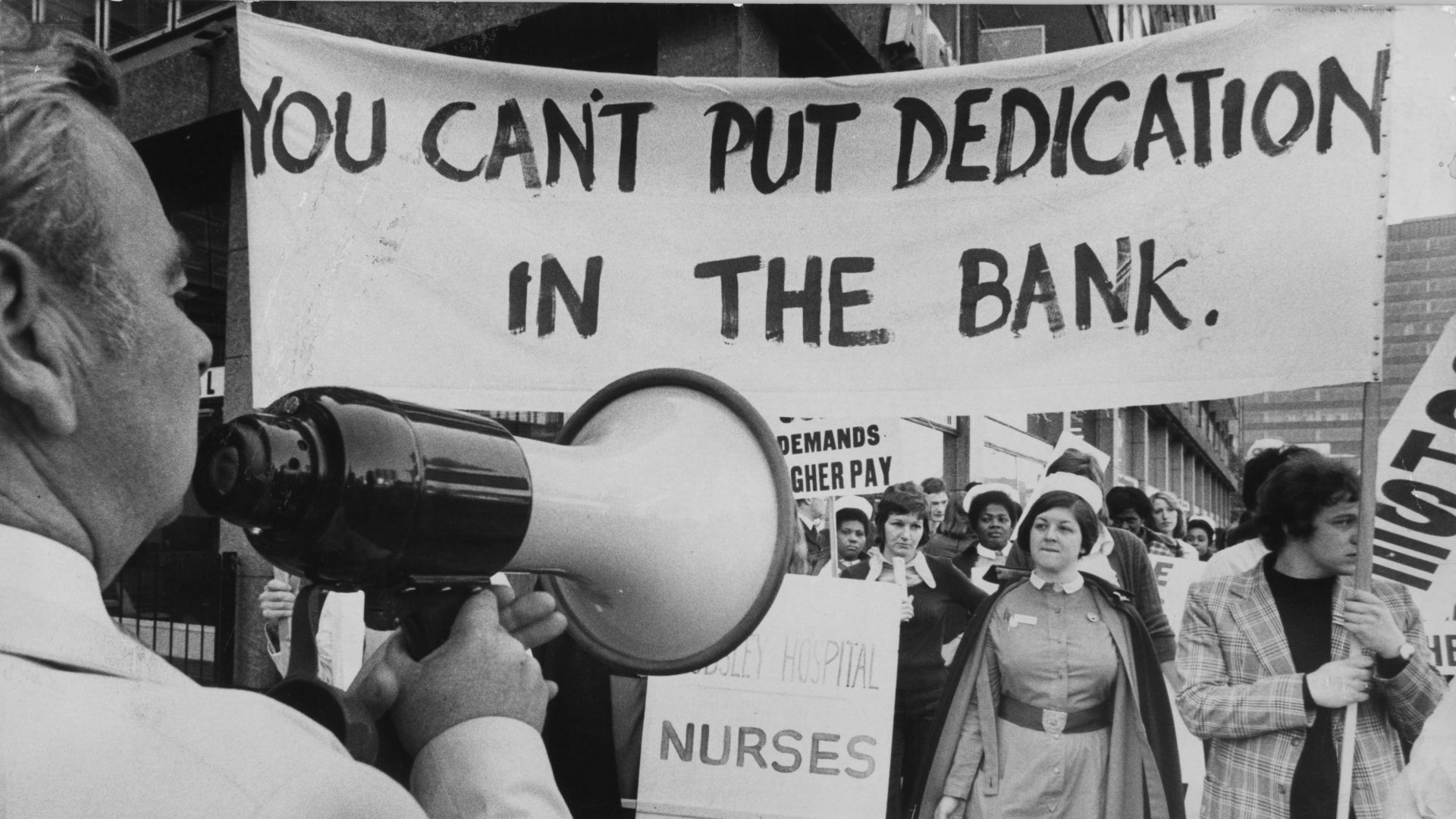

The reality of current healthcare is that it’s still available but, increasingly, you’ll have to pay for it. This, some would say, is the ultimate goal – the market takeover. Those who can’t afford to pay will join the ever-longer queue waiting to be seen by increasingly exhausted staff. Why are the NHS’s nurses and doctors exhausted? Because there aren’t enough of them and there will be fewer as working conditions deteriorate further. “Workforce planning” is the responsibility of government. It sets budgets for medical schools and so determines how many doctors will be trained. It sets pay for nurses and doctors. “Austerity” has shaped the workforce. More “austerity” will pile on more exhaustion. Slowly but surely, it will drive healthcare professionals towards private clinics.

Not all, of course. Just enough will remain: enough to provide a much weakened service. If it were not so serious, it would be almost funny to listen to the chair (until recently) of the Health and Social Care Committee, one Jeremy Hunt. His laments about the NHS sit oddly with the fact that he was the health secretary for over six years and thus was responsible for “workforce planning”. Now he’s chancellor and preparing us for more austerity.

The fate of people who rely on the NHS is ineluctably bound up with social care. The past decade has seen its steady collapse, caused by massive cuts to local authorities’ budgets, together with caps on what they may raise through tax. This means that thousands of patients ready to leave hospital cannot, because there is nowhere for them to be looked after. A comfortable care home is there for those who can pay. For the rest, it’s a hospital bed in which you are a “bed blocker”.

Was there really nothing the government could have done over the past dozen years? Or was its death by a thousand cuts the slow march to a new world in which the market dominates the health service?

The invasion of Ukraine and the pandemic have provided cover for the parlous state we are in. But every other major economy has weathered these challenges. And no one seems to have the courage to point to the elephant in the room, aka Brexit. Brexit was going to bring £350m a week to the NHS. Instead, the NHS is clapped out.

But even at this late hour, the dreamer can imagine a resurgent NHS. The Beveridge Report in 1942 served as the blueprint for the introduction of the welfare state and the NHS. It was widely welcomed even by the Daily Telegraph. The Labour Party under Attlee, once elected in 1945, put its vision into effect, changing the face of postwar Britain. Can we hope now for a second chance to realise the dream? We cannot afford not to. Beveridge had recognised that only a bold vision would bring the necessary improvements in the nation’s health and welfare.

It will need the politics of optimism, hope and ambition, and a commitment to the values of fairness and caring, to rejuvenate our health system. It will have to supplant the hypocrisy and cynicism that characterises much of our current politics. It must reject the policies and politicians whose only concern is getting through the day, or indulging in a nostalgia for a time that never existed. It will need courage, vision and a clear strategy.

It will need a vision for the NHS that takes into account the relationship between health, healthcare and social care, a massive increase in the ratio of healthcare professionals to the population, appropriate financial investment and, whisper it loudly, a grown-up discussion about what to do with that damned elephant. Prof Sir Ian Kennedy is a leading expert in the law and ethics of healthcare and in health policy and has advised governments and the World Health Organization.

Prof Sir Ian Kennedy is a leading expert in the law and ethics of healthcare and in health policy and has advised governments and the World Health Organization