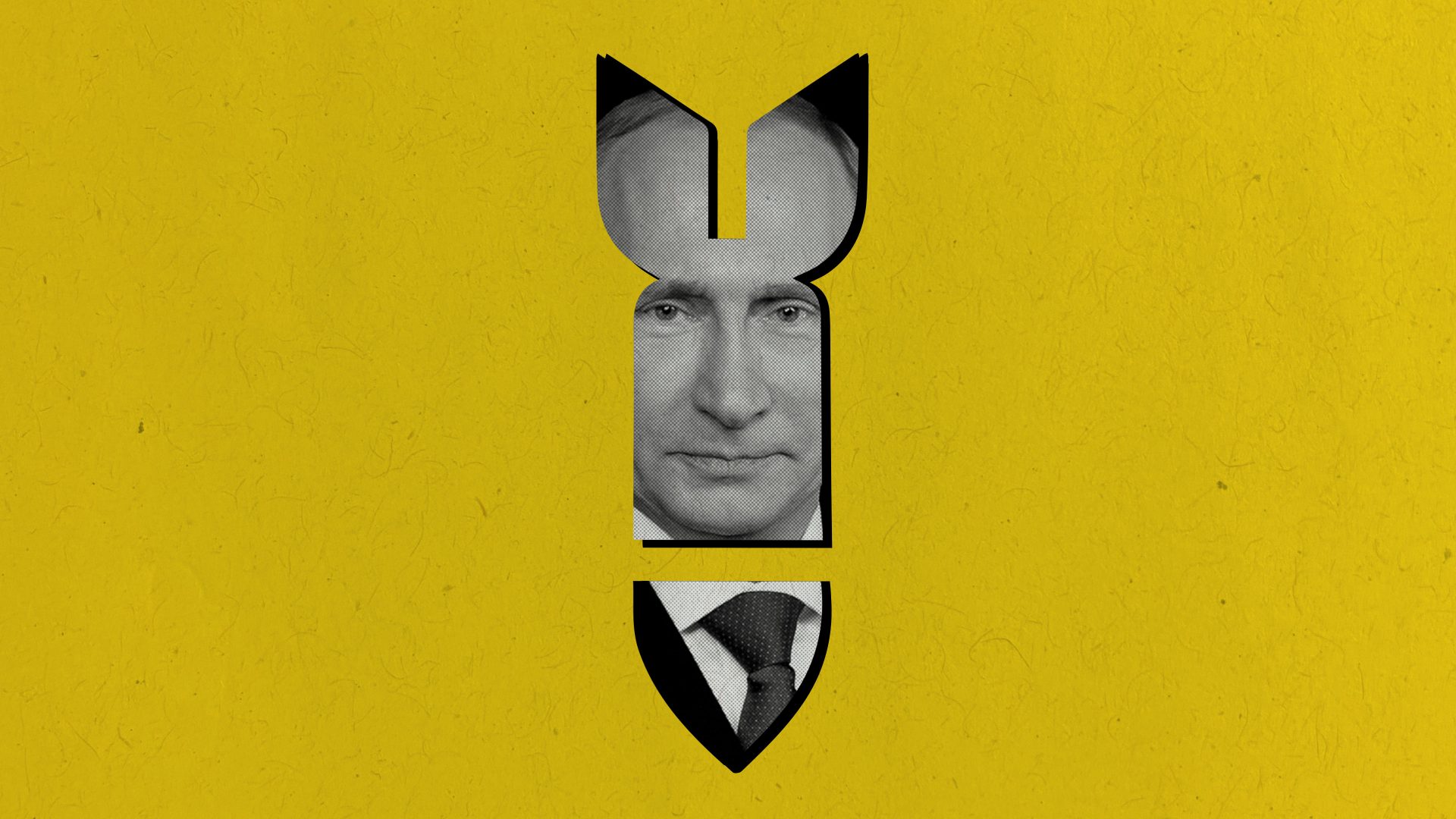

Concerns about the possible use of nuclear weapons moved right up the political and military agenda after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Vladimir Putin’s decision, apparently with the support of Alexander Lukashenko, to install tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus follows earlier threats from Putin about the use of nuclear weapons based in Kaliningrad, Russia’s Baltic territory. In May 2022, Russia stated that its forces had carried out simulated nuclear missile strikes in Kaliningrad, a territory that borders the European Union.

The nuclear issue has also combined with uncertainty about the stability of the Russian leadership, notably following Yevgeny Prighozin’s coup attempt on June 23rd, and the recent arrests of senior Russian generals and detention of critics. The Wagner mutiny included a direct challenge to the Kremlin’s whole justification for the war in Ukraine and was the most direct assault that Putin has seen in his 23 years in power.

The invasion, and the events that have followed from it, have put European security under severe strain. This has driven a significant increase in defence spending in many European states, and a shift in public and government alignment which has led both Finland and Sweden to seek NATO membership. While Russia’s main focus remains its war in Ukraine, the risk of conflict in the Baltic Sea region remains.

Despite the sabre rattling it remains extremely unlikely that a nuclear weapon will be used in Europe, particularly in the Baltic Sea region. And yet, the world has lived for decades with the threat of a nuclear strike. The consequences of any nuclear attack even at the lowest tactical level would be disastrous. A high priority needs to be given to reducing nuclear risk.

Though there have been some close moments, notably the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, the barriers to the use of such weapons have stayed intact since 1945. It remains a hurdle which no Russian leader, whether Putin or a successor, has any intention of deliberately crossing. Use of nuclear weapons remains an irrational response to any military situation. It is difficult to imagine any tactical use in the Baltic region that would not have major consequences for Russia, including St Petersburg, irrespective of any NATO response.

The Western view is that a nuclear guarantee is essential to defend the Baltic states and NATO allies from any Russian conventional attack of the kind that we have seen in Ukraine. The overwhelming superiority of Russian conventional forces in the region, even after the attacks in Ukraine, remains a deep concern, as is the fact that in the last decade Russia has been renovating its nuclear forces and expanding its delivery systems.

The many military setbacks that Russia has experienced in fighting Ukraine reduces its capacity to threaten other countries, but these threats have not been removed. Moreover the psychology of successive Russian leaderships suggests that, even if they experience major defeats, the threat of aggression remains. Countries at risk, particularly in the Baltic, have no choice but to work on the assumption that the threat of Russian invasion remains an active possibility. Their historical experience reinforces that assumption. That is why there is no sign of the NATO defence guarantee being removed.

A further aspect of this question is the extent to which NATO members in the region, particularly the new members Sweden and Finland, permit nuclear weapons to be installed on their soil. While the moral argument against such installations has been removed by the decision of Belarus to accept Russian nuclear weapons and Russia’s decision to highlight nuclear threats from Kaliningrad, it would not necessarily be wise for further tactical nuclear weapons to be installed in NATO countries in the region.

In certain circumstances agreed limitations upon the installation of tactical nuclear weapons in the region could be a productive subject for discussion with Russia.

At this point, it seems certain that the NATO strategic nuclear guarantee for NATO member states in the region will remain, and also highly unlikely that Russia will deliberately resort to use of tactical nuclear weapons, though it will no doubt continue to broadcast the threat of such action.

However, this does not make it impossible that tactical nuclear weapons could be used in the region. There are serious possibilities of low level escalation, accidentally or otherwise. Russia certainly sees the accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO very negatively (though this can be overstated, since for a number of years Sweden and Finland have cooperated closely with NATO and Russia is very well aware of that).

Possible cyberattacks from Russia as well as air and maritime challenges could lead to conflicts. Russian threats in all of these fields have escalated since 2014.

And there are similar worries relating to access to Kaliningrad, Russia’s Baltic enclave. For example in June 2022 the Lithuanian ban on the transit of sanctioned goods across its territory to and from Kaliningrad raised tensions. These settled down fairly quickly, but similar issues could arise in relation to sea access to Kaliningrad.

Since the 1970s twelve NATO Allies have signed bilateral “Incidents at Sea” military agreements with Russia to limit the possibilities of, and hopefully prevent, accidental contacts at sea outside territorial waters that brought the threat of escalation. These include the United States (1972) and the United Kingdom (1986), but only Germany (1988) on the Baltic Sea. There is a strong case for forging similar agreements between Russia and the NATO member states in the Baltic, updated to deal with modern technological and military changes.

In recent years the Baltic States have already developed their own resilience and preparedness against threats from Russia. These need to be supported. And there is a long history of Finnish-Russian co-operation in jointly managing their 1,340km border, but such measures are less effective in a crisis.

These immediate measures in the region would reduce the risk of nuclear confrontation. While many Baltic countries are ready to encourage nuclear disarmament, that can only be from a basis of security (possibly including a permanent Western presence in the region).

But there remains a lack of clarity about the best ways to reduce nuclear risks. Proposals to do so fit broadly into three areas: military, nuclear force posture and capabilities; military doctrine and intention; and communication and relationships. All three of these are important and the kinds of measures described above address the force posture and doctrine points.

But better communication and understanding are essential, both between allies and adversaries. The uncertainties caused by both political realignments and emerging disruptive technologies such as AI and cyber have uncertain impacts, which need full consideration.

These are difficult issues, as governments have to manage the changing balance between facing down Russian aggression and nuclear risk reduction. They need to address differing elements of nuclear risk, particularly the key difference between strategic and tactical weapons, and their relationship with nuclear deterrence. And of course they need to negotiate.

At the heart is the problem of how to prevent Russian aggression, both in Ukraine and more widely, and then how to find the best means of dealing with Russia in building a secure future. The NATO Summit in Vilnius called on Russia to recommit – in words and deeds – to the Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear Weapons States issued on 3 January 2022, on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races. That is an essential precondition for making progress.

Charles Clarke is the former Home Secretary.

On July 19th the Centre for Geopolitics and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, from Cambridge University, jointly hosted a panel on Nuclear Risk Reduction in the Baltic Sea Region, to begin the process of gathering proposals in these fields.