It is more than eight years since the UK narrowly voted to leave the EU, and more than four since we formally left on the deal negotiated by Boris Johnson. You could be forgiven for thinking that would mean that the tangible impacts of Brexit – new import and export checks, longer queues at the border, and the like – were over; but this would be mistaken.

Small businesses that sold food or drink to the EU have largely left the trade due to the checks and inspections required post-Brexit, making life harder for businesses in an already difficult sector. But new EU rules coming into force this month are set to spread that trouble to any business still selling products anywhere in the European Union – including Northern Ireland.

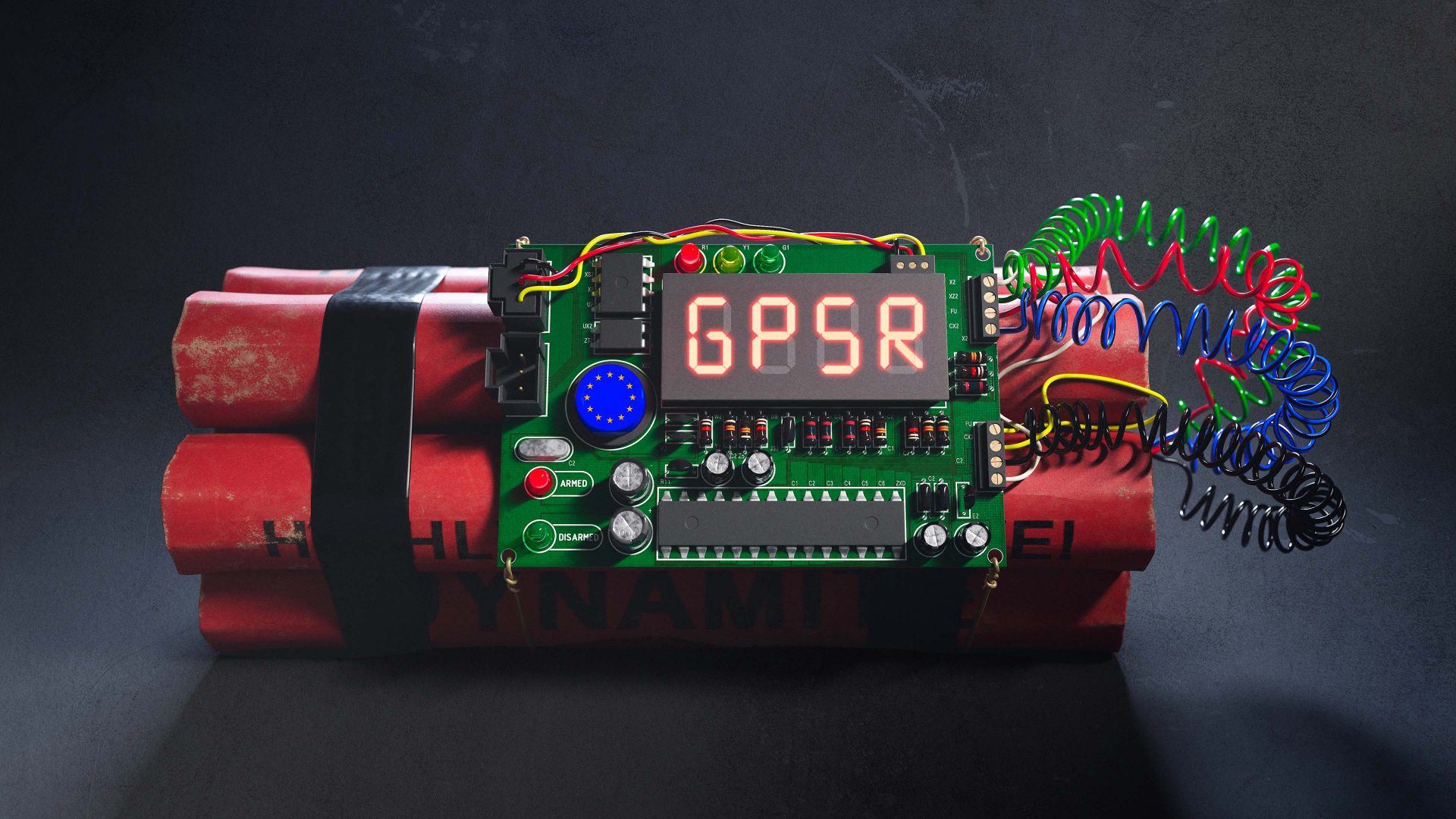

The update to the EU’s General Product Safety Regulations (GPSR) is set to be a disaster for small businesses across the UK – many of whom don’t know it yet, because just weeks before the rules take effect on December 13, the government has done almost nothing to prepare businesses for what’s coming.

Most of the regulations are straightforward, and just update existing ones. At their core, the rules require products to comply with existing safety standards, or if they’re not covered by anything specific, to have a risk assessment and appropriate information on the packaging. There is a bureaucratic headache in that this has to be labelled in the language of the country it is going to – which definitely qualifies as a hassle – but if the UK were in the EU, that would be no big deal.

The problem comes in one specific new requirement: any product sold within the EU must have on its packaging a named point of contact located inside an EU country. Thanks to Brexit, the UK no longer meets that criterion, meaning anyone exporting a product after December 13 is in violation of the new regulations.

For bigger businesses, this is easy enough – they already have offices in multiple countries, and can just designate one of these as the point of contact for GPSR. Medium-sized companies might find themselves in trouble, though – and small businesses are saying it means they will just have to stop their EU sales entirely.

“We sell strips of cotton that are two meters long,” says Yvann Stephens, co-owner of The Specky Seamstress, a haberdashery business, who says the bias binding they mainly sell is hardly the most hazardous product on the market. “It’s 100% cotton. It’s dyed with nice, safe dyes that are compliant with whatever safety regulations are required. But like, let’s not kid ourselves. It’s a piece of fabric.”

There are companies that offer to be the point of contact for importers, but they charge around €150 a year for each product line. Despite being identical in safety terms, each different pattern of bias binding is a different product – meaning that even if the admin was manageable, the cost of selling to the EU would be insurmountable.

“It is endlessly frustrating for those of us who were opposed to Brexit in the first place. If we were still in the EU this would not be a problem,” says Stephens.

Andrew Hutchings runs a small business called Retro Supplies, which sells components for restored Amigas, and similarly will have to ditch his EU sales, though because of the terms of Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal, he is cutting off sales to Northern Ireland too, as it is still covered by EU regulations. He feels lucky that he even knew the new regulations were coming.

“My wife found it on the Federation of Small Businesses website and sent me a link to it,” he explains. “I’m not sure how she found it, probably through some other social media.

“I suspect it’s to stop bad Chinese products coming into consumer markets – you know AliExpress and Temu and things like that… And it has completely blindsided everyone, literally in the last week. As far as I’m aware, there’s nothing from the government about any of it.”

The situation is even more difficult for small businesses that sell their products through Amazon. Many of the goods on that site now are sold by small businesses, which either ship them directly or, more often, let Amazon handle the fulfilment of the products through their famously efficient distribution network.

Amazon requires that businesses using its “Fulfilled By Amazon” service sell to the whole of the UK, which means that anyone using their logistics network has to comply with GPSR even if they have never sold to anyone in the EU – because the products have to be available to buyers in Northern Ireland. That leaves them either finding a way to comply with the new rules, or else looking for a new distributor.

The changes are manageable for the kind of old-school business that produces one product and sells thousands of identical copies of it across the world, which would need to pay just once for a responsible EU person, costing a mere few hundred euros a year.

But the UK is full of small creative businesses made viable by EU exports – whether that’s jewellery sellers on Etsy, artists, designers or any number of other trades. Because each of their products is distinct, the rule change seems set to shut them out of the export trade entirely, leaving some furious that they are only discovering this through social media and word of mouth.

“Bang goes my Irish trade. Fantastic. Just what I needed,” posted Rich Hardiman, owner of Comic Printing UK, on Bluesky.

“This is just another in a series of shocks to small business that add up to a crippling blow,” he said. “Just keeping up with red tape that can be directly traced to Brexit has become a major administrative task that, at a time when people are already struggling, feels increasingly unsustainable. The UK just doesn’t feel like a good place to try and make a go of small business any more.”

Each of the three business owners contacted by the New European expressed their frustration and disappointment that the government hadn’t done anything to let them know about the forthcoming changes – let alone lobbied the EU to try to mitigate or delay their impact.

The only content on gov.uk relating to GPSR is technical policy documents and a site advertising two online events by the UK Export Academy. When contacted by the New European about the dearth of information or outreach, a spokesman for the Department for Business and Trade said: “We are supporting SMEs across the whole of the UK to get ready for GPSR and will be publishing more guidance shortly.”

The department did not specifically respond to questions asking whether it had been caught out by the changes, whether the absence of guidance represented the priority placed on small businesses by the department – but the fact the advice is still only coming “shortly”, just days before the new regulations take force, speaks volumes.

The GPSR is just a single set of regulations, and in the scheme of things not even a hugely significant one – at least not for the countries inside the union. But it serves as a reminder that no matter what politicians say, Brexit will never be over.

We are still outside the economic union of which every single one of our neighbouring countries is a member. It will continue to make new rules and regulations, and those will always have a major impact on the UK economy – only now we are unable to directly influence that process (where once we had an effective veto).

The opt-out doesn’t change the reality of us having to comply with EU rules if we wish to trade with them, and without international trade the UK’s future is as a small, poor island on the very edge of the continent.

At some point, the government will have to wake up to the reality that the UK doesn’t have a meaningful long-term future outside the EU – at least not if it wants to remain a major economy.

But if GPSR is Labour’s first test, it has absolutely flunked it, failing to manage even the basics that the last government managed, of raising awareness among businesses, or playing a role working with Amazon to address fulfilment issues.

Keir Starmer’s unwillingness to tackle the big issues of Brexit will become apparent with time – his current process of staking everything on a “reset” of relations with the EU is, ironically, the identical strategy his predecessor tried – but the lack of grip on the practical stuff is alarming.

It is one thing to look for a “third way” when none exists: the UK isn’t about to become the 51st state of the USA, and Starmer has ruled out meaningfully closer integration with Europe. That’s a strategic mistake that will either eventually contribute to Labour’s downfall, or else be reversed.

But failing to grab the details in time speaks of a broader malaise: Labour was elected because the people of Britain wanted a change, and they wanted competent people in charge. As Labour’s dismal approval numbers show, unless it gets its head in the game soon, it will fail on both fronts.