Walking into St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta, Malta is like walking into the canvas of a particularly lush and sumptuous artwork. Every inch of its arches and pillars and domed ceilings is covered with carvings and paintings, in plush golds, reds, purples, blues. The floor is made entirely of coloured inlaid marble, each slab a tomb for the Knights and Officers of the Order of St John. The epitaphs are mostly concerned with victory and death; angels with triumphant trumpets, death with a sickle and an hourglass, the warning of time passing. Then beneath the opulent curved ceiling of the nave, depicting scenes from the life of St John, stands the main altar bedecked with a purple and red canopy. It houses an enormous statue of the Baptism of Christ.

The cathedral has not always been quite this ornate. When it was built in the 16th century, the interior was rather modest and more in keeping with the unassuming exterior, with its almost military-like appearance. The main entrance is flanked by two large bell towers and a clock. For the first 100 years, the cathedral stayed like this, until it was remodelled in the 17th century by the designer Mattia Preti in high baroque style. The soft, Maltese limestone made a perfect surface for carving each pillar and archway.

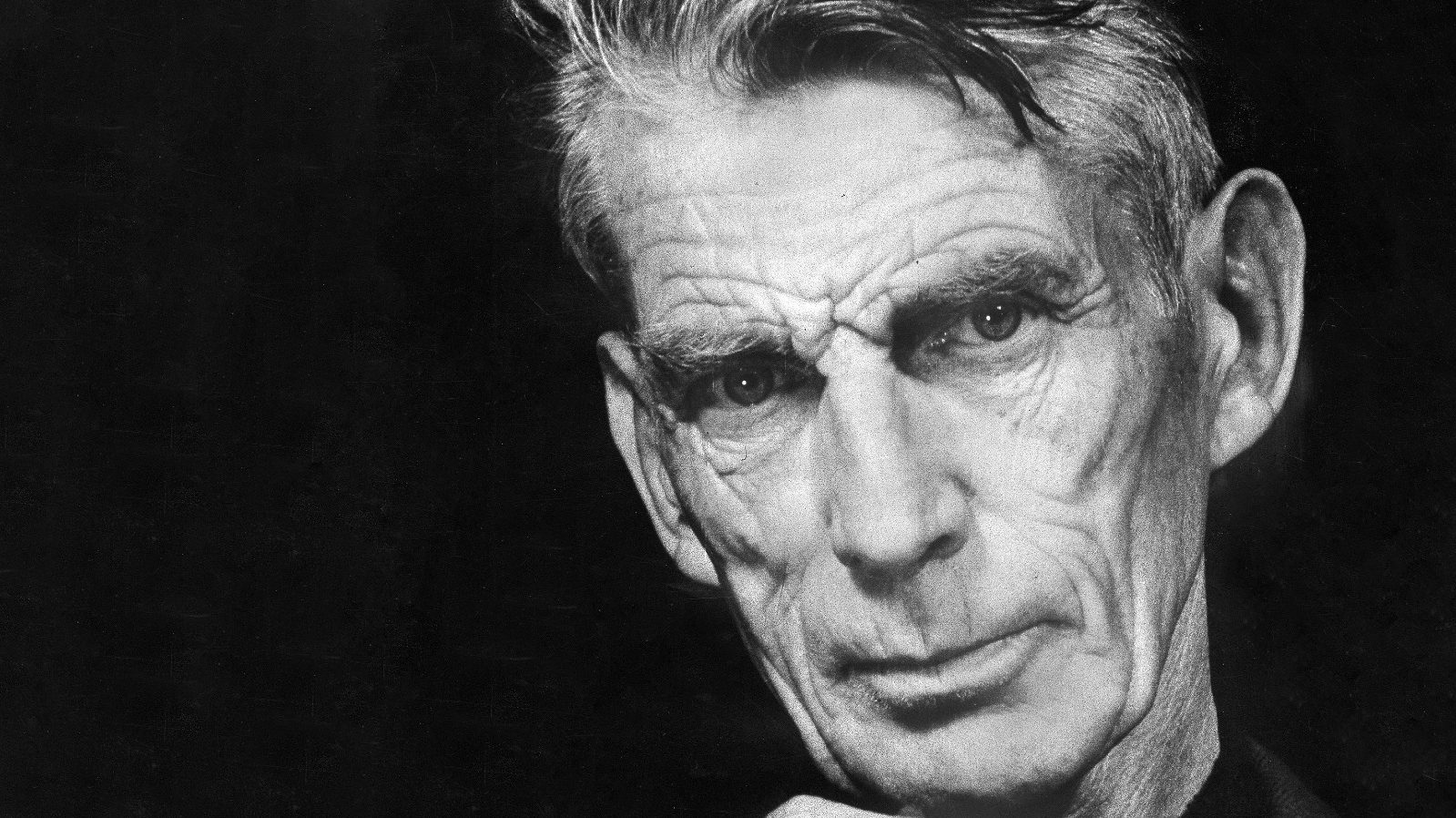

It was this sight that would have greeted the writer Samuel Beckett when he walked through the doors one autumn day in 1971. Beckett was staying on the island with his wife, Suzanne, just north of Valletta in the Selmun Palace hotel, but a trip to the town brought him to St John’s Cathedral, almost certainly to see the treasure housed in the oratory. For, just to the right of the main entrance there is a room with large, wooden doors. When these are thrown open, they reveal an astonishing sight.

A black, white and terracotta tiled floor leads to a rug-covered set of steps and hanging there on the wall, above a small altar, is a Caravaggio. The Beheading of St John the Baptist was commissioned as an altarpiece by the cathedral after Caravaggio fled to Malta to escape a murder charge in Italy. By joining the Order of St John, the painter was able to dodge any charges that may have been brought against him and stay in relative safety, protected by the Knights. In 1608 he completed this canvas, his largest painting, which has been described as the greatest painting of the 17th century.

It is certainly large, measuring 12ft by 17ft, and employs the classic Caravaggio chiaroscuro technique of tonal contrasts (chiaroscuro literally translating as “light-dark”). This brings about the effect of illuminating certain figures in the scene, casting an almost divine light on them, creating drama and tension. Combined with a classic Caravaggio gloominess, the effect of a spotlight is intensified further, resulting in what came to be known as tenebrism – dramatic illumination.

The Beheading of St John is dominated by an inky-black canvas, with much empty space. Certain features are just visible in the dimness. A barred window to the right of the frame shows two figures peering out. A large, brick archway dominates the background, centre-right.

Yet focus is drawn to the two highlighted men at the front of the canvas. The executioner bends over the prone figure of John the Baptist in the throes of finishing off the beheading. A sword lies on the ground, as the executioner reaches for a small dagger – the knife of mercy – to remove the still partially attached head. Salomé bends over the figures expectantly holding a golden platter, while another man in a blue cloak points at the plate, as if instructing where the head should be flung.

But there is another person in this painting, and it is this figure that caught the eye of Samuel Beckett. An elderly woman stands in the group watching the execution, aghast. Both her hands are clutching her head, perhaps partly in anguish, and partly to drown out the macabre sound. The scene is pure horror and violence. A red river of blood streams from John the Baptist’s neck, pooling at the bottom of the canvas, dead centre. In the 1950s when the painting was restored, a curious ghostly detail became visible. Caravaggio had signed his name in the blood, making this the only known, signed painting of his today.

On that autumn day in 1971, Beckett spent a full hour looking at this painting. Standing, unmoving, he absorbed every detail, concluding that it was “a great painting, really tremendous”. And during that hour he also began to play around with the gaze, placing himself almost as part of the painting itself, writing to the author and scholar Edith Kerns, “I behold both the horror and its being beheld.”

Then, in surely one of the most unlikely scenarios in literary history, he was booted out of the cathedral for being “improperly dressed”. Samuel Beckett, sartorial savant, improperly dressed… it’s hard not to speculate what on earth he was wearing.

Beckett didn’t do anything immediately with his experience. Like many writers, it sat there fermenting away. And neither was it unusual for a writer to be inspired by a work of art. In the late 1950s, during a paralysing bout of writer’s block, Sylvia Plath used art to break the strangling grip, writing poems based on paintings by Paul Klee, Henry Rousseau, Arnold Böcklin, and Pieter Bruegel. But Beckett held on to this image, only for it to emerge six months later, after a five-week trip to Morocco in February 1972.

Beckett biographer Deirdre Bair describes what happened one sunny afternoon at a pavement café. Beckett spotted a woman wearing a djellaba, a loose robe, crouching at the side of the road. She appeared to be intensely waiting, and every so often would stand up, peer into the distance, and flap her arms, before crouching down again. Beckett watched entranced, and a little mystified.

Eventually a school bus arrived, the woman kissed and swept a child into her arms and disappeared into the crowds. There was something about that encounter that made Beckett ingeniously combine the Caravaggio painting with the waiting woman, resulting in the literary genesis of his play Not I. But it was a genesis that had roots as far back as 1963, when Beckett first started toying with the idea of a play that would feature a woman’s face, alone, in constant light.

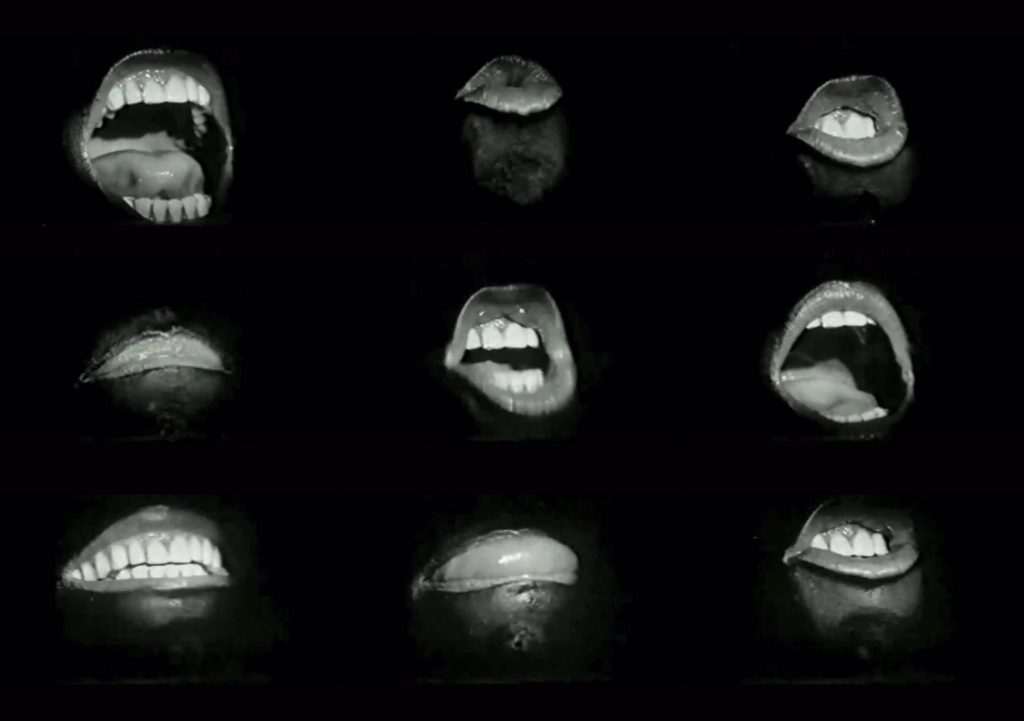

Upon his return home to Paris, Beckett wrote Not I quickly, in just 12 days. The spotlighted, horrified face of the old woman in the Caravaggio, emerging from the gloom, became one of the main inspirations for the disembodied mouth, the only visible feature on an otherwise pitch-black stage illuminated by a beam of light.

The Mouth delivers a series of monologues in jumbled sentences at break-neck pace, telling the story of a woman, roughly aged 70, who has suffered some unspecified trauma. Thinking this must be a punishment, the Mouth goes over events from her life, hoping to uncover what it is she is being punished for and what she needs to confess. In addition to a continual buzzing in her head, there are moments when the Mouth appears to be listening to voices that the audience cannot hear. Equally, she is tormented by the constant light. But earlier versions of the play also feature a mysterious character downstage right, the Auditor, a hooded figure that raises its arm at each break in the monologue. It was this figure that was inspired by the waiting woman in Morocco. When Beckett was asked if it was supposed to be a guardian angel or death, he shrugged his shoulders, flapped his arms, and remained silent on the topic.

The play premiered in November 1972 at the Forum theatre in the Lincoln Center, New York, directed by Alan Schneider, with Jessica Tandy playing the Mouth, approximately a year after Beckett had first seen the Caravaggio in Malta. Then, in January 1973, it opened at the Royal Court in London with Billie Whitelaw in the role.

Because the Mouth was the only visible thing on stage it was crucial that the actor did not move, in order to keep the Mouth precisely in the beam of light. Whitelaw found herself strapped into a chair, draped in black, with her head in a vice. Not surprisingly she described performing it “like falling backwards into hell”. In a later interview, Whitelaw explained how they wanted to offer no escape for people in the theatre, either, so against all the rules they removed the light bulbs at the exit doors and in the toilets, so the audience had to remain with the relentless Mouth that would not let them go.

Possibly one of the most famous performances of the play was not for the medium of theatre at all. Whitelaw reprised the role and was filmed on February 13, 1977 for a BBC programme called The Lively Arts, Shades, Three Plays by Samuel Beckett (available to watch on YouTube). The focus is solely on the Mouth. By now the Auditor had disappeared from the production, and this was something Beckett appeared to remain undecided about. Sometimes he would let the role be dropped due to difficulties lighting it effectively, other times he would reinstate the figure, lighting it even more prominently from above.

Whitelaw recalled his absolutely meticulous involvement in the staging. At rehearsals, she would see him watching intently from the stalls and putting his head in his hands every time she got a word wrong. After Beckett’s death, Not I continued – and continues – to be staged, performed by actors including Julianne Moore, Juliet Stevenson, Lisa Dwan and Jess Thom.

One of the joys of studying writers is unravelling their influences, seeing what they ingest and then what emerges from that ingestion. Although Beckett described both the Caravaggio and the waiting woman as his two main influences, there were probably others, too. Scholars have suggested Nicolas Poussin’s The Massacre of the Innocents and the film Battleship Potemkin.

But there is something wonderful imagining Beckett in Malta, strolling into St John’s Cathedral and becoming captivated by the Caravaggio, his writerly eye taking in each detail of a painting that has hung there for centuries and remains there today. The cathedral oratory offers a darkened respite from the cooling, blue air of Valletta on an autumn afternoon, storms out at sea grounding the ferries. The large, wooden doors are thrown open six days a week to reveal the astonishment of a spotlighted murder, a gruesome beheading. Yet there is something about that face, the elderly woman’s face, illuminated with horror, and looking down as she has done for the last five centuries. Little wonder Beckett found himself so haunted.

Gail Crowther is a freelance writer, researcher, and academic. She is the author of The Haunted Reader and Sylvia Plath