Marbella is a mirror of the man who made it. The Spanish resort city that plays host to countless reality show D-listers “flaunting their curves” for the delight of tabloid and magazine readers has also recently made the headlines as the place where Vladimir Putin’s ex-wife has been scrambling to sell properties ahead of EU sanctions, and where the doorman at The Only Way Is Essex star Elliott Wright’s beachside restaurant was killed while trying to break up a fight.

“Marbs”, as it has become known – “no carbs before Marbs” being a Towie catchphrase celebrating joyless dieting in the name of getting beach-body ready – is a place where wealth and glamour is cut through with corruption and violence. All featured heavily in A Town Called Malice, a 1980s-set series about the city that screened on Sky earlier this year, and will do again in Marbella, a drugs-and-crime drama that was being filmed there this summer.

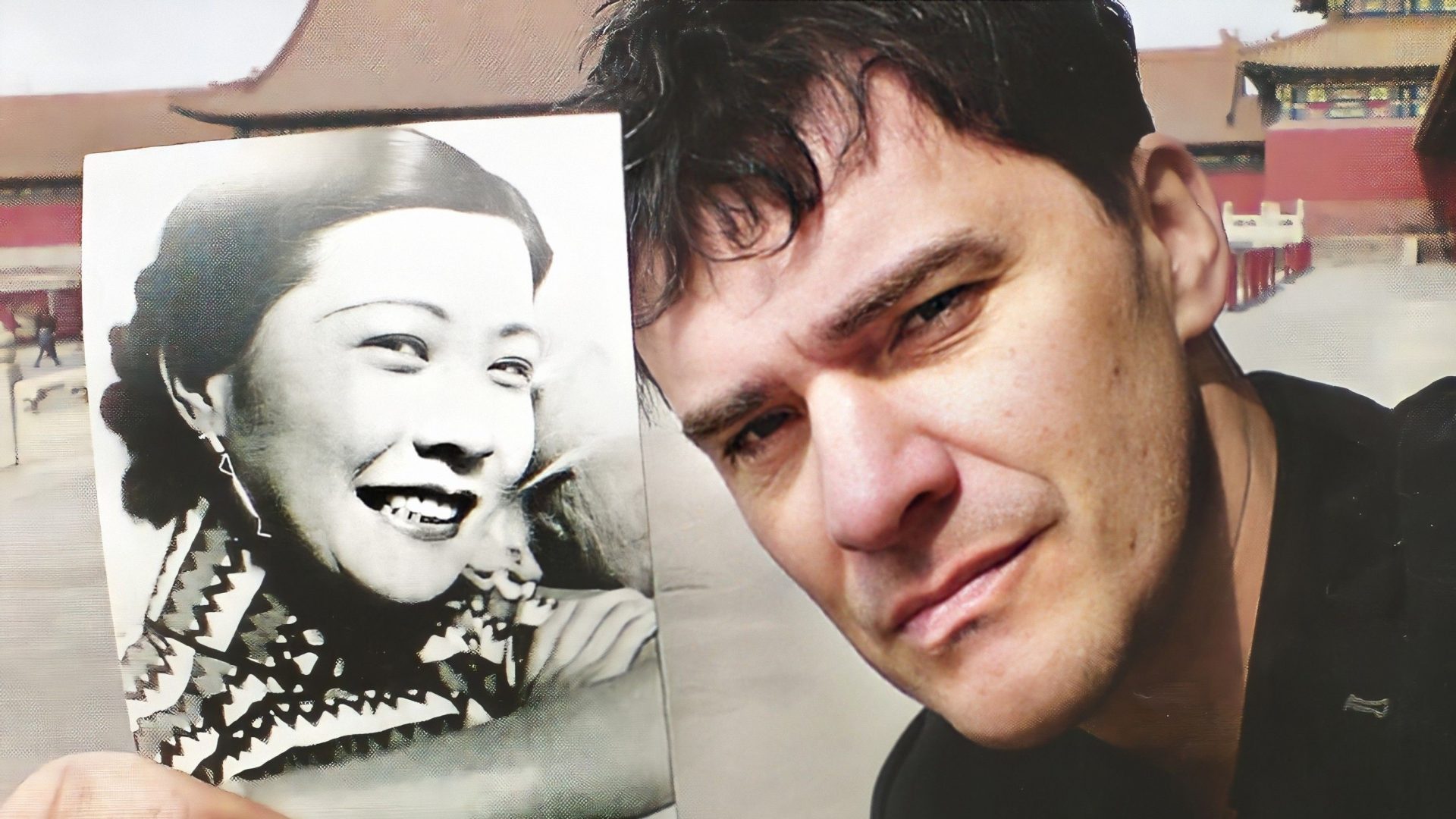

Glamour and corruption were also the twin faces of Jesús Gil y Gil, mayor of Marbella in the 1990s, and a man who shaped the resort as we know it.

A heady mix of Robert Maxwell, Peter Stringfellow and Boris Johnson, the corpulent, medallion-wearing mayor defined “larger than life”, starring in his own TV show, on which he conducted phone-ins while sitting in a hot tub surrounded by bikini-clad women. That programme achieved a 40% viewer share across Spain in the summer of 1991, when Gil was already famous as the volatile president of Atlético Madrid, known for threatening to feed his players to his pet crocodile, abusing referees and firing managers on a whim (“Sacking a coach is like having a beer,” he said).

But Gil’s story had begun much earlier. As an aspiring property tycoon in the late 1960s, his first major project had ended in death, disaster, and prison time. Pardoned by Franco himself, Gil would later install a bust of the dictator in Marbella City Hall in a clear sign of the sort of man he wanted to be. But beneath the seedy, fascist-sympathising exterior was a desire to become a genuinely great man. Gil had grand dreams of landscapes, cities – Spain itself – transformed. His epitaph, he said, should be “Here lies an imbecile who thought… that Spain could have been better”, and the scale of his ambition left an indelible mark on the country, for better or worse.

Lunch was just about to be served when the roof fell in. Hundreds of Spar supermarket employees had gathered for a function at Gil’s Los Ángeles de San Rafael luxury development, near Segovia, central Spain, on that June day in 1969. To bag the contract, Gil rushed the newly built restaurant into service, and the cement was not yet set. Film of the aftermath of the collapse shows starched tablecloths and place settings eerily undisturbed, but a yawning chasm in the floor and blue sky above. Fifty-eight people died, the coffins ranged row upon row at the mass funeral. It was found that the building had neither an architect nor proper plans, and the 36-year-old Gil was sent to prison for five years.

While a lesser man may have faltered, Gil was one of life’s great survivors. He simply decked out his cell with carpet, a desk and a typewriter, and continued to run his business from prison. And, since the rule of law was never an absolute concept in Franco’s Spain, he was freed after just 18 months. Gil’s indomitable mother – a widow who had survived the Spanish civil war by becoming a successful black marketeer – had relentlessly petitioned the authorities for his release. It would be both the focus on looking after no 1 that she had hardwired in him, and the experience of growing up in a country in flux where anything was possible, which meant Gil did not miss a beat in getting back on the path to success.

Jesús Gil’s first job had been as a bookkeeper of a Madrid brothel. Or that was the story that he, a man hardly unaware of the value of weaving his own myth, used to tell. “I didn’t know it was a brothel,” Gil told a TV interviewer in 1995, “I was innocent, I was tender, I knew nothing. I was going to be a vet…” That last part was true, but for a young man of Gil’s temperament, there were greater prizes in a rapidly changing Spain.

By the time Gil entered his third decade in 1953, he had already made his first million in the used-car trade, and Spain, too, was on the up. The Pact of Madrid of that year marked an emergence from postwar isolation, and the economic liberalisation policies brought in to tackle the 1950s inflation crisis made Spain the second fastest-growing economy outside of the Communist world by the following decade. Construction was booming, and for those with the stomach for the kickbacks and the dodgy dealing, millions could be made. Gil – always able to get his own way and with a questionable moral compass – was a man born for that world.

But for Gil, it had – at least at the start – been about more than money. “I am,” he said in 1968, “or at least I see myself, as a creator”, and while Los Ángeles de San Rafael had a clear commercial focus, serving the demand for holiday homes among the growing Spanish middle class, it was also Gil’s vision of an ideal city. Despite being almost slap bang in the centre of Spain, it brought the coast to the mountains, with a reservoir and a yacht club – a fine metaphor for Gil’s belief in his ability to remake the world according to his will. But soon Gil would turn his attention from making a faux seaside paradise to staking his claim to the coast proper.

Marbella was synonymous with wealth and luxury well before Gil set his sights on it. The Spanish-born German aristocrat Alfonso de Hohenlohe had opened the Marbella Club Hotel there in the mid-1950s, attracting the international super-rich and transforming Marbella from a little fishing village into a rival of the chic Côte d’Azur resorts. In the 1970s, serious money arrived as Prince Fahd of Saudi Arabia built a vast palace in the hills, complete with its own mosque. His rare visits with his large entourage would pump millions into the local economy almost overnight.

Gil built his first project in Marbella in 1987, a glittering white block of luxury apartments. Naturally, the building had none of the proper permissions, and he immediately fell foul of the local authorities. But in the years that followed – years when the social habits of dictatorship lingered – he would just pay the necessary bribes and carry on building. That soon proved not to be enough for Gil, however, and an idea formed: rather than sidestepping permits, why not become the man with the power to issue them?

Gil’s straight-talking campaign pledge in the 1991 run for mayor was “I’ll make you all rich. And I’ll clean the shit off the streets of Marbella”. Presenting himself with populist aplomb as an ordinary Spaniard in sympathy with the little man, he won a resounding victory. Once in office, Gil kept the second of those promises – or at least, what he had meant by that promise – paying off the homeless to go elsewhere while the police, and sometimes Gil in person, roamed the streets intimidating other “undesirables”. But while Marbella was a haven for every wealthy comic-book villain going, cementing its reputation as the capital of the Costa del Crime, the average citizen profited little as building boomed and money was laundered through development.

Under Gil, the face of Marbella was transformed. “Rural” land was redesignated “urban” with abandon, with Gil’s attitude to ecological sensitivity being “I’ll build a house on the branch of a tree”. Marbella was hardly alone, as town halls up and down the Costa del Sol became financially reliant on the taxes and permits associated with building, and bribery abounded. But Marbella stood as the ultimate example of the over-development of the costas, with Gil – its fleshy-faced poster child – sealing his public image through his Las Noches de Tal y Tal TV programme (The Nights of Such and Such – “tal y tal” was Gil’s typically unsophisticated catchphrase).

By the time homes across Spain were tuning in to watch the mayor in his hot tub, he had added silverware-winning football boss to his list of titles. Atlético Madrid bagged the Copa del Rey the same summer Gil secured the mayoralty, lifting the cup again in 1992, and winning the La Liga/Copa del Rey double in 1996. Club president Gil, like the fans, was euphoric. “With my popularity,” he said, “I could be God.”

But football would ultimately spell Gil’s downfall. With both shameless front and clear PR genius, Gil secured the city of Marbella as Atlético Madrid’s shirt sponsors just ahead of the 1991 mayoral election. Gil was briefly imprisoned in 1999 and barred from public office when it was found that, as mayor, he had funnelled 450m pesetas (over £2m) from the city council to his football club for this purpose. And it was, by that time, his football club. In an incredible feat of financial sleight of hand, Gil had taken a majority share when the club became a PLC in 1992, for which a three-and-a-half-year sentence was later handed down.

Gil died in 2004, aged 71, before that sentence could be served. He left behind a bitter legacy. As Gil’s fortunes began to change, Atlético Madrid ended the 1999-2000 season facing relegation for the first time since 1934. The PLC conversion left fans with just 3% of the club while Gil’s son, Miguel Ángel Gil Marín, remains the main shareholder to this day.

Marbella Council was dissolved in the same way as mafia-infiltrated Italian councils. The city will be repaying debts dating from Gil’s mayoralty until 2040, and up to 30,000 properties illegally built during that time still stand, many of them blighting the landscape. It is this that is Gil’s most enduring legacy.

Yet, despite all the self-serving roguery, Gil inspired devotion until the end, with 15,000 fans lining Atlético Madrid’s stadium for his funeral. Some said he had faked his own death – so great was his charisma, it made it hard to believe it could be extinguished. Gil’s ultimate appeal was that he represented the ambition in everyone to become something greater than themselves, and what still attracts those to Marbella today is what perhaps had attracted Gil, too – the sense that it is a place where anyone, by means foul or fair, can become someone of consequence.

A Town Called Malice is available to stream on Now TV