We all have that short list of writers we really love, the ones we gush about to people, whose books we press on them as gifts. Then there is the next level, the writers whose work resonates with us so sonorously it’s almost as if they were writing just for us. These writers feel so personal that we rarely mention them in conversation, as if even talking about them will betray some unwritten contract binding us to our intimacy.

Their work means so much to us that, when we meet someone who likes them too, our shared admiration immediately takes that fledgling friendship to an exalted level, as if receiving the ultimate character reference.

When I meet someone who’s heard of Ivor Cutler, I know I’m probably going to like them. When I meet someone who is a fan of Ivor Cutler, well, we’re practically lying in a field of daisies describing the clouds to each other from the get-go.

It’s 17 years this week since Cutler’s death but the more aesthetically pleasing mathematics are found in this year marking the centenary of his birth. A small series of events is taking place this month at London’s South Bank Centre to mark the anniversary, and January saw the publication of the first full-length Cutler biography.

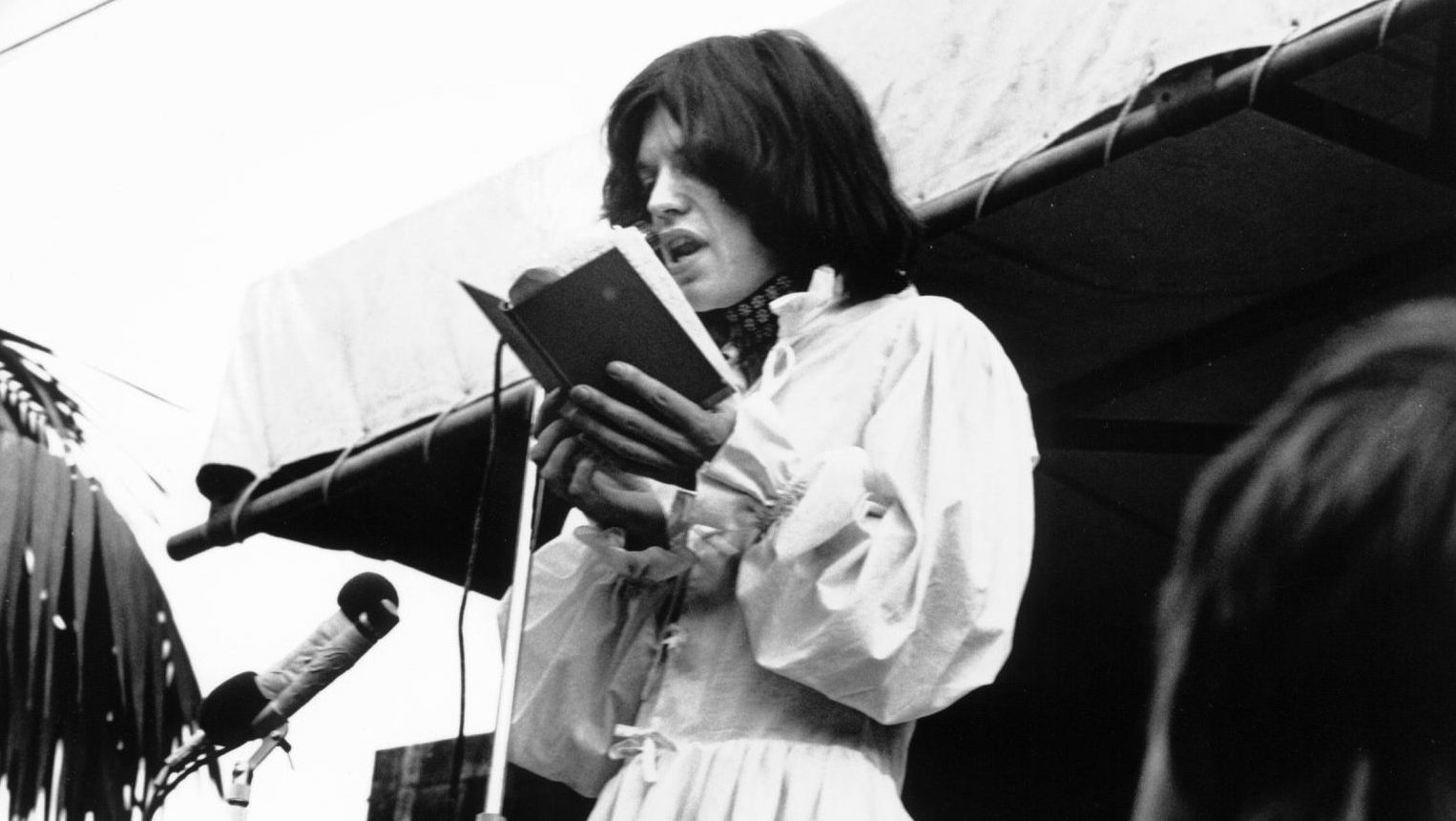

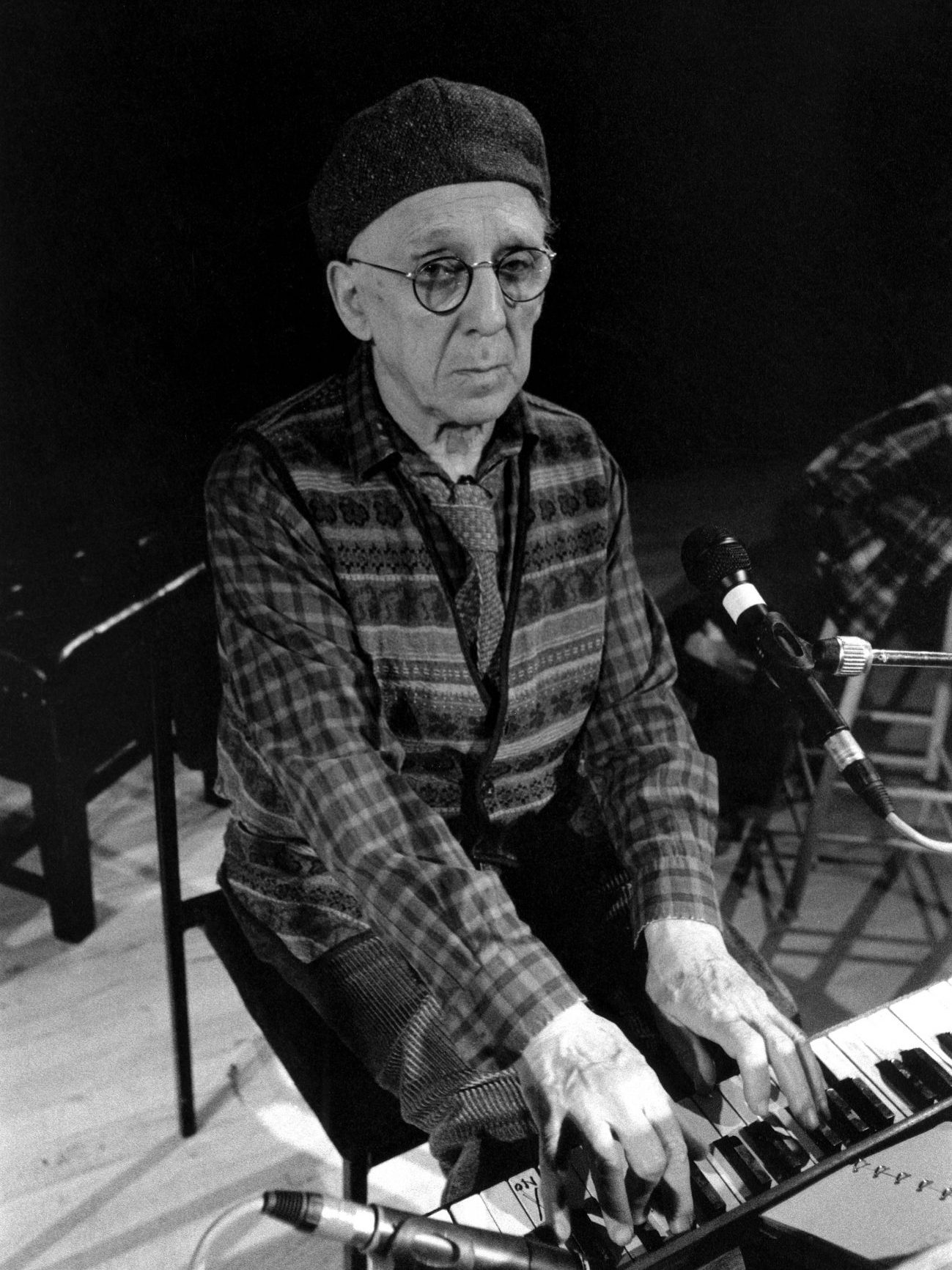

Like most people, I first heard Ivor Cutler on John Peel’s radio show, then saw him for the first time on Whistle Test in the mid-1980s: an old man with a serious face behind owlish glasses sitting at a wheezy harmonium with the word “SEWER” painted on the base wearing a strange straw hat and crooning a short song about shoplifters (“Is your shop right down on the ground? Then let us lift it, lift it for you.”). Later he reappeared with an even shorter song, delivered in the same deadpan manner, insisting he was happy and ending the performance abruptly by pretending to punch himself in the face.

Growing up in a soulless suburb between soulless suburbs, sitting there in my school uniform, I knew the world was never going to be quite the same again.

Nobody looked like Ivor Cutler, wrote like Ivor Cutler or sounded like Ivor Cutler. He was a poet, storyteller, musician and artist, a man admired by a range of the great and good from Bertrand Russell to KT Tunstall, a man who John Lennon and Paul McCartney liked so much they put him in their Magical Mystery Tour film as the bus tour guide Buster Bloodvessel. George Martin produced one of his albums and he was invited by John Peel to record more sessions than anyone except The Fall.

He made three appearances at the South Bank’s annual Meltdown festival, invited by separate curators Peel, Laurie Anderson and Robert Wyatt. He appeared on the opening night of BBC2 and at the turn of the 1960s was a regular fixture on the BBC Home Service. Alan McGee signed him to Creation Records in 2000, making Cutler, at 77 years old, a labelmate of Oasis.

He hated hotels, muzak, air conditioning and noise, remaining an active member of the Noise Abatement Society to the end of his life. At what turned out to be his final concert at the South Bank in 2004, the compère introduced Cutler with a request from the artist that the audience restrict their applause to half their usual volume. On more than one occasion during the show he responded to applause by putting his fingers in his ears – no quirky affectation; he was genuinely pained by the sound.

He wrote stories for adults and children, poems, songs and aphorisms, created complex works of art and contributed cartoons to Private Eye and Punch. His work was joyful and sinister, hilarious and heartbreaking, whimsical and dark. There was wisdom in his nonsense, kindness in his curmudgeonliness, subversion in his cosiness. There was nobody like Ivor Cutler. Nobody even close.

The eccentricity of Cutler’s work is what appealed to me most. Some of his output is pure nonsense in the Edward Lear tradition but most of it has more substance than is first apparent, despite the brevity of the stories and poems. Maturity, for example, from his collection Fresh Carpet, reads in its entirety: “To combine public altruism with private self-interest and unwitting hypocrisy is quite a trick, but I think I have it now”.

Cutler’s was an oblique view of the world, seeing life through a prism that shifted it slightly from the view everyone else endured, observing quietly before delivering quirky philosophical gems about what he’d noticed. Reading Ivor Cutler, whether one of his stories – which were usually no more than a page and a half long – or a four-line poem, is like stepping off the world and letting life ease past you for a moment. Reading or listening to Cutler is being given permission to daydream, an invitation into his world as a brief respite from the real one.

Cutler himself was a notorious daydreamer. Having volunteered for the RAF in 1942 and trained as a navigator, he was dismissed because he became so distracted by the clouds he’d disappear into reveries.

A naughty interviewee who invented stories about himself, the wartime navigator dismissed for dreaminess was one of Cutler’s stock tales, some of which turned out to have little or no basis in fact. His brief RAF career largely checks out, however, and we know this thanks to Bruce Lindsay’s Ivor Cutler: A Life Outside the Sitting Room.

It’s a credit to Lindsay that he has produced such a meticulously researched and definitive biography because Cutler was a nebulous mythmaker and entirely unreliable narrator. That Lindsay has not only managed to root out salient fact from scattergun fiction but also written a thorough and highly readable work that is affectionate yet well short of hagiographic makes this a valuable biography of a man that even those who knew him best found contradictory and hard to pin down.

The title is a play on Cutler’s Life in a Scotch Sitting Room Volume 2, a 1978 album that became a book and appears to be a series of autobiographical tales of Cutler’s childhood, some straightforward, others fantastical. Lindsay’s title may well be a wry nod to the difficulty of his literary task.

One thing the book confirms is that Cutler was a genuine eccentric. There was nothing arch about his penchant for wearing plus fours and a range of outlandish hats, no affectation in his proclivity for dishing out stickers with short messages on them of his own devising, ranging from “befriend a bacterium” to “made of dust” to “add 15 inches to your stride and save 4½% of insects”.

Like most eccentrics, however, there was a melancholic vulnerability behind the whimsy. Cutler was born into a Jewish family in the Govan area of Glasgow and suffered antisemitic prejudice and bullying throughout his childhood, from his peers and even from his teachers. In addition, he did not receive the unrequited love from his mother on which most children can rely. He suffered throughout his life with depression.

“Ever since I was born, more or less, I’ve always seen myself as a lesser being,” he wrote. “It’s all based on my mother’s relationship with myself and her not really loving me.”

We enjoy our eccentrics, our dreamers, our whimsical jesters riddled with quirks, and perhaps like to think that’s all there is to them. Yet beneath the surface, you’ll usually find some kind of embedded trauma. Of the other subjects featured in the Ivor Cutler and the Eccentric Miscellany season at the South Bank this month, Vivian Stanshall and Bruce Lacey both suffered with crippling anxiety while Margaret Rutherford lived her life in constant fear of inheriting the mental illness that drove her father to beat her grandfather to death with a chamber pot in a Matlock boarding house.

For them, and people like them, early fear, trauma and anxiety somehow fosters an innate kindness, gentleness and a unique view of the world, one slightly withdrawn, slightly askew yet soaked in empathy that makes them who they are. That was true of Ivor Cutler, who dedicated his story collection Fremsley to “the timid – the truly and constantly courageous” and recognised the inner child in people that was never allowed to truly flourish in himself. It was to those inner children that he was speaking.

“Those who come to my gigs probably see life as a child would,” he said. “It’s those who are busy making themselves into grown-ups, avoiding being a child – they’re the ones who don’t enjoy it.”

I correspond occasionally with my old English teacher from school, a rare beacon of kindness there who tried harder than anyone to coax me out of my own paralysing timidity. Recently I sheepishly reminded him of the school essay I once submitted about Ivor Cutler. He replied: “One thing I remember about you is your keenness for Ivor Cutler – a sign of your individualism and non-conformity”.

I can’t see us ever lying in a daisy field looking at clouds, that would be weird, but the feeling of recognition and validation that message gave me even all these years later is similar to what unites Ivor Cutler fans, the embrace of a skew-whiff outlook on life that makes it OK to be a dreamer, OK not to conform, OK to embrace your own individuality and run with it.

As the man himself put it in his poem Creamy Pumpkins: “When the land tilts, run north. Leave the family. You are the important one, the dreamer. The world needs its dreamers. Heads like creamy pumpkins. Quiet skin. Eyes that swivel round like smoke, like turquoise, like bulby grapes. Seeing, where others face an empty flat wall”.

Ivor Cutler: A Life Outside the Sitting Room by Bruce Lindsay is published by Equinox, price £25.

A EUROPEAN LIBRARY

74. ITALIAN JOURNEY by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, trans.

WH Auden and Elizabeth Mayer (Penguin Classics, £12.99)

Undertaking a long journey for the benefit of his mental health, Goethe set out on a tour of Italy in 1786, later turning the letters he wrote home from Venice, Rome, Naples and elsewhere into one of Europe’s earliest and best travel narratives.

A fascinating account of a writer and country on the cusp of a new and glorious cultural dawn.