“We are,” wrote Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking, “imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves.”

The death of a cultural figure we admire can invoke tangible grief even when we don’t know them personally. In the case of a musician, say, or a sports person, there’s a sense that they were living out our dreams and taking us along with them.

When they’re on stage or on the field, while we’re awed by the expression of their outrageous talent, there can be a sense of projection, of proxy, of how that could be us up there if only our fingers didn’t turn into sausages when we pick up a musical instrument or if the coordination we’ve been blessed with wasn’t similar to that of Frankenstein’s monster on roller skates.

There’s an innocence about this kind of admiration, as if we’re granting a select few individuals custody of our hopes and dreams. When we learn of

their deaths, it’s as if those dreams have died too, a portion of our innocence snuffed out with the ceasing of a distant heartbeat.

It’s slightly different with writers. The ones we admire most, whose deaths have the most profound effect, are those who reflect something of ourselves back to us. This time we keep hold of our hopes and dreams and instead allow theirs into our worlds, nurturing an intimacy born of the one-to-one relationship between writer and reader that’s different from the shared experience of the stadium or concert hall.

Writers invest their hopes and dreams in us, turning the relationship into a deeply personal one. We have spent many hours in their company while turning the pages of their books, utterly absorbed in the worlds they create, the secrets they share and the realities they conjure for us.

When one great writer dies the sense of loss is profound enough. The deaths of five great writers in the space of barely a fortnight, as happened last month, sees the world lose a little of its sparkle.

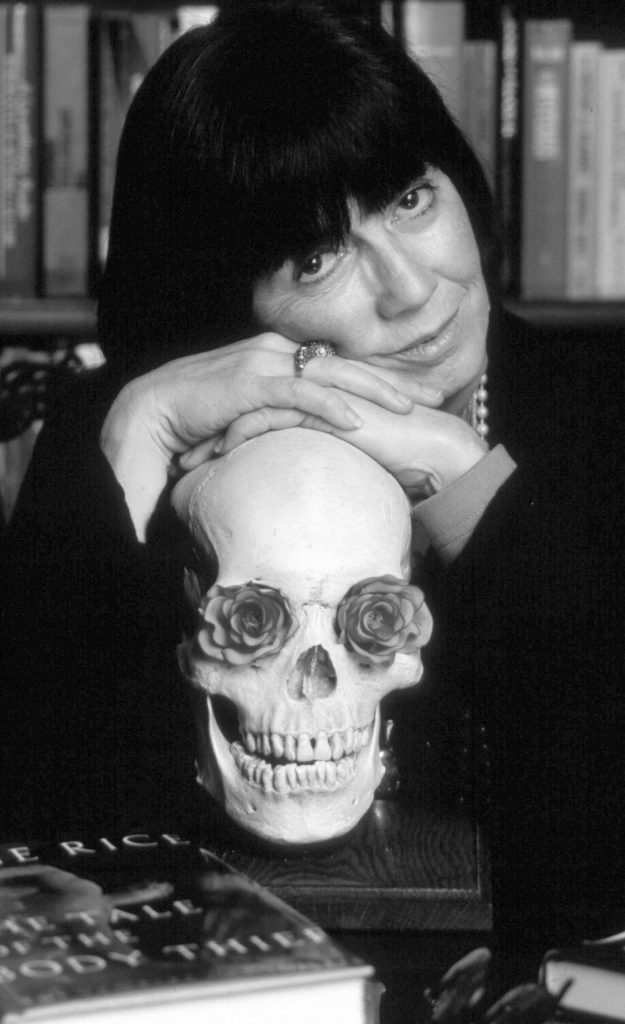

First, there was Anne Rice, author of a string of best-selling gothic novels including 1976’s Interview With A Vampire, who died in California on December 11. Four days later the pioneering Black feminist writer bell hooks died at her home in Kentucky. On December 17, we learned of the death of Eve Babitz, unparalleled chronicler of Californian excess, in Los Angeles, followed six days later in Manhattan by the great Joan Didion.

Finally, Keri Hulme, winner of the 1985 Booker Prize with The Bone People, died in her native New Zealand on December 27. Seventeen days, five of the world’s greatest contemporary writers: has there ever been a more ruthless period of literary mortality?

The effect of their collective absence from the world is incalculable, but even individually each writer represents a searing loss to their fans all around the world. On hearing the news, many people would have gone to their bookshelves, pulled out a spine-creased, furry-cornered copy of, say, hooks’ Ain’t I a Woman or Babitz’s Eve’s Hollywood and flipped wistfully through pages where the prose still thrums with as much life as it ever did.

There are those who will have read their first bell hooks or Keri Hulme in the 1980s, their first Anne Rice or Eve Babitz in the 1970s and their first Joan Didion during the 1960s. They may even have felt their lives changed as a result. They will have been different people to who they are now, and news of the writers’ deaths will have prompted sadness as well as a deep nostalgia for their own past selves.

“Our favourite people and our favourite stories become so, not by any inherent virtue but because they illustrate something deep in the grain, something unadmitted,” wrote Didion in her 1968 essay collection Slouching

Towards Bethlehem, capturing a sense of why the death of a writer can affect us so profoundly.

We can look back on old recordings and footage of musicians and sportspeople and notice them becoming more dated as the years pass, the images grainier, the hairstyles dodgier. The pictures and sounds created in our minds by our favourite writers remain the same but it’s us that change. When we run a finger along the spines of their books, we gain a sense of the different people we’ve been over the years and recall the locations where we first read them, the people who inhabited our lives back then.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” wrote Didion in The White Album, and we lace our own stories into those that writers share with us, each favourite book an anchor dropped in our lives.

The five authors who left us in December all lived relatively long lives, with hooks the youngest at 69, and Didion the eldest at 87.

With the possible exception of hooks, there’s no real sense of death snatching them prematurely from the world, that we’ve been deprived of their work by death (albeit Babitz produced nothing new after suffering serious burns in 1997 when she accidentally set fire to her clothes when lighting a cherry-flavoured cigar at the wheel of her car).

The women were all very different writers and different people, who leave a legacy of remarkable quality and variety. In addition to her ground-breaking works of Black feminist thought, hooks also wrote literary criticism, children’s stories, self-help volumes and poetry. Rice wrote gothic novels while producing erotic fiction under a nom de plume.

Hulme, meanwhile, other than some short stories and three slim volumes of poetry, invested everything in The Bone People, spending 12 years on a novel that was rejected by several publishers, while she rejected publishers herself because they wanted to make changes to the text. She eventually placed the book with a small, independent, feminist press in New Zealand and, a year after publication, won the Booker (Hulme didn’t fly to London for the ceremony thinking she had no chance. When she received the news over the phone, she responded: “Bloody hell”).

As for Babitz and Didion, their lives managed to be parallels and opposites. When each reached the end of their teens, Didion was embarking on a degree in English literature at the University of California while Babitz was writing a letter to Catch-22 author Joseph Heller that began “I am a stacked 18-year-old blonde on Sunset Boulevard. I am also a writer.”

Didion met her husband John Gregory Dunne in her mid-twenties and they remained together until his sudden death from a heart attack at the dinner table 40 years later. Babitz never married and had relationships with Harrison Ford, Jim Morrison, Annie Leibovitz and Steve Martin.

She was once photographed naked playing chess against (a clothed) Marcel Duchamp to irk a married lover who’d taken his wife to the opening of the artist’s exhibition instead of her. “In every young man’s life there is an Eve Babitz,” said record company executive Earl McGrath. “It’s usually Eve Babitz.”

Didion built her literary reputation as the person in the corner quietly observing while Babitz was always at the heart of the party. Both women were formed by Los Angeles: Babitz the personification of its brash

vivacity, Didion exercising a cool detachment in the face of the city’s excesses while absolutely immersed in its character and lore.

“A place,” Didion wrote, “belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his own image.” She could have been describing Babitz as much as herself and there’s something faintly appropriate in how these two extraordinary writers died within days of each other.

Yes, we still have a huge body of brilliant and varied work to draw on but the deaths of these five writers with almost four centuries of life and work between them still removes something precious from the world.

At the Sydney Literary Festival last year, the novelist Michelle de Kretser said: “When a writer dies, it is often said that they will live on in their work. Like all clichés, that’s both true and woefully inadequate. Words on a page are no substitute for the irreducible mystery of their presence.”