The service at St Martin-in-the-Fields to commemorate Martin Amis last week was a sad but beautiful occasion. It was also inspiring. The very last words to be spoken, in a medley of recordings of Amis’s own voice, were drawn from his great memoir, Experience: “You have got work to do”.

Yes, that’s right. Amis, in 1995, was reflecting upon what lay ahead of him as his father, Kingsley, approached death. But his words, in 2024, had a broad and contemporary impact, too. It is, indeed, time to get busy.

Barring a sudden upheaval in the space-time continuum, there will be a new government on July 5 and probably one with a hefty Commons majority. This will be a moment of huge relief – 14 years of Conservative rule is more than enough – but also of daunting challenges. As he becomes prime minister, Keir Starmer will face much heavier expectations than did, say, Margaret Thatcher in 1979 or Tony Blair in 1997.

The paradox of this election campaign has been that the main parties have reached a grubby, unspoken pact to talk as little as possible about the most important subject. The Tories don’t want to discuss their greatest failure; and Labour doesn’t want to upset the imaginary homogeneous bloc of voters in the “red wall”.

True, there have been a few token breaches of the pact. On Monday, Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, made a guarded promise in the Financial Times “to improve our trading relationship with Europe”, a pledge apparently specific to the chemicals industry and greater mutual recognition of professional qualifications with the EU.

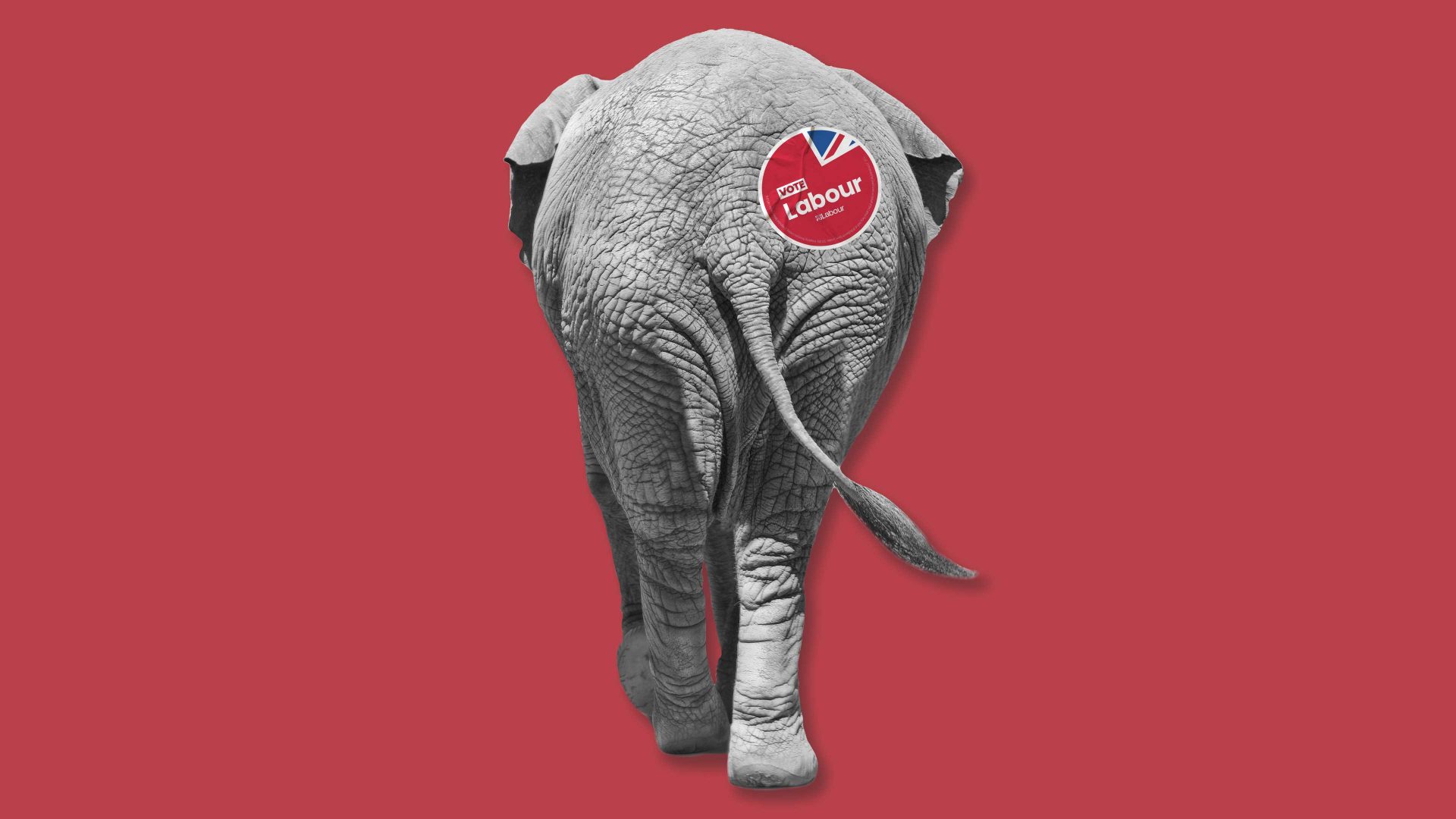

In practice, the question of Brexit and what to do about it has been hidden in the attic until further notice. It has often been referred to as “the elephant in the room”; but the extent of the denial reminds me rather of the classic moment in Mel Brooks’s Young Frankenstein, when Frederick Frankenstein, played by Gene Wilder, addresses Marty Feldman’s Igor, hunched and deformed: “You know, I’m a rather brilliant surgeon. Perhaps I can help you with that hump”. To which Igor replies: “What hump?”

This is self-evidently untenable. Only two weeks after the election, on July 18, prime minister Starmer will find himself hosting the fourth meeting of the European Political Community at Blenheim Palace, bringing together 50 leaders from across the region, to discuss its future. What does he plan to say?

Those of us who would like to see this country reclaim its membership of the EU must not wait for politicians to take the lead; or even expect them to turn the dial from “craven” to “curious” in a hurry. But we can set out the reasons why they need to overcome this aversion – and very soon.

The first step is one that will be painful for the foot soldiers of the referendum and ratification years. Between the 2016 vote and January 31, 2020, at 11pm, when the UK formally left the union, a titanic battle was fought by an alliance in parliament, in the media and on marches to prevent (or at least delay) disaster. It was defeated, but not for want of trying.

The elephant trap set by the defenders of Brexit is for us simply to resume that campaign. They want to caricature us as restorationists, weak-willed nostalgists, a heritage movement unsuited to the tough realities of the 21st century.

They want us endlessly to relitigate the referendum, to argue about buses, and unlawful prorogation, and the removal of the whip from decent Tories, and Daily Mail headlines, and all the other crimes and misdemeanours of those grim times.

They want us, implicitly, to demand an apology from the electorate that will never come (voters don’t say sorry). They want us to say “I told you so” as Brexit continues to hollow out the British economy.

They want us to be as insufferable as Hillary Clinton was after Donald Trump’s conviction on 34 felony counts, hawking mugs that bear the inscription: “Turns out she was right about everything”.

We need to admit that we were outplayed eight years ago. The Remain campaign was from Venus; Leave was from Mars. We were defeated by tougher and more disciplined people. The fact that they were also crazy and plunged the country into a state of populist mayhem and economic decline makes it all the harder to accept this.

But it is true nonetheless. This is the cactus that has to be hugged. The question now is: do you want to bask in your moral rectitude, or do you want to be effective? Choose.

To get the UK back into the EU an effort of the imagination is required, and it begins with a thought experiment: what if the UK had never been a member of the union? What would be the patriotic case, sharply specific to the 2020s, for applying to join now? Why would Britain be stronger as a member?

Harold Macmillan famously failed to get past the original velvet rope of the EEC, thanks to De Gaulle’s first veto in January 1963. But he understood, with much greater clarity than Churchill and Eden before him, why the UK needed to be in the European club.

Post-imperial Britain, he recognised, could not afford to be isolated between the American superpower and the “boastful and powerful ‘Empire of Charlemagne’” that he believed De Gaulle intended to build. In August 1961, Macmillan told the Commons: “I believe that our right place is in the vanguard of the movement towards the greater unity of the Free World and that we can lead from within rather than outside”.

The objective was not achieved until January 1973, by Edward Heath, who had been part of the project from its inception. And the duration of this diplomatic feat is a warning to today’s pro-Europeans. Now, as then, joining the EU will be a task of great political, diplomatic and economic complexity.

The case for membership should be built step by step and it must be, to use the American term, “bleeding edge” in its modernity. Naturally, it will draw attention to the fact that the “securinomics” which Rachel Reeves promises will be impossible without access to the single market and customs union. There is no “magic growth tree”, except in Liz Truss’s head.

In fact, I suspect that this case will make itself. If Labour really wants to transform our public services, address inequality, and fix broken Britain, it will sooner or later have to shift its ground on the UK’s economic relationship with the EU.

A better place to start is defence, and David Lammy, the shadow foreign secretary, has already begun the preliminary work. In an important essay in the May/June issue of Foreign Affairs, he made the case for a new “progressive realism” and declared that “European security will be the Labour Party’s foreign policy priority”.

Most significantly, he wrote that “the European Union and the British government have no formal means of cooperation. To address that problem, the United Kingdom must seek a new geopolitical partnership with the EU”.

This is both necessary and potentially transformative: pitch-rolling for Starmer, who will inherit a fast-mutating geopolitical landscape.

It is certainly true that US isolationism will be turbocharged if Trump wins in November. But America’s gradual renunciation of the role of global policeman is not only driven by the MAGA movement.

It was, after all, Joe Biden who messily and ingloriously withdrew from Kabul in August 2021. He has done his best for Ukraine, but – should he secure a second term – his patience will not be limitless.

Sooner than many grasp, Europe will need its own, radically enhanced defence collaboration; and that requirement will exert a powerful gravitational force between the UK and the EU. This is a hard concept of Europe, not one of comfortable cohabitation, warm words and long lunches in Brussels.

Next, pro-Europeans in this country must find new ways of managing and talking about immigration that are more than different shades of macho posturing. Naturally, Nigel Farage’s pantomime entrance to the race has dissuaded the main parties from doing anything other than to stick to their scripts (Tories: small boats and Rwanda; Labour: cracking down on the gangs).

But one of the few truly memorable moments of the campaign to date was Beth Rigby’s skewering of Sunak in last week’s Sky News Leaders’ Special. “Net migration into this country has more than doubled in the last three years, from before we left the European Union,” she told the PM – rising from 836,000 to 1.9 million. As he tried to respond, Sunak looked like an emotionally devastated claymation character from Wallace and Gromit.

The point being: even if your objective is to bring down immigration, Brexit isn’t working. And, in any case, the objective is too crude.

It has fallen to Stephen Flynn, the SNP’s leader in Westminster, to say what nobody else will: “The problem is we don’t have enough migrants”.

Labour’s claim that its skills revolution – yes, one of those – will supply British workers to fill all the vacant jobs, especially in the NHS and social care sector, is absurd even on its own terms. Those vacancies need to be filled now.

An essential milestone on the road back to the EU will be a recognition that sovereign insularity in a globally interdependent labour marketplace is neither achievable nor desirable. And, when it comes to asylum seekers, Sunak can talk all he likes about small boats and Suella Braverman can rant all she pleases about “existential challenges”. Reality doesn’t care about rhetoric.

The World Bank expects that there will be 260 million climate refugees by 2030, and as many as 1.2 billion by 2050. Clearly, the only way to deal with this will be through international collaboration and well-resourced, compassionate and swift systems of border management.

A symmetrical argument applies to climate change itself. Pro-Europeans should press home the obvious point that national strategies alone are woefully insufficient and encourage competing parties to water down their commitments (witness Sunak’s shameful postponement of net zero targets and Starmer’s ditching of his pledge to invest £28bn pa on green projects).

Only supranational collaboration can give us half a chance, at this late stage, of keeping the earth inhabitable.

What all this has in common is that it is rigorously future-facing. It replaces anger and grief about what happened in 2016 with a relentless focus upon the difficulties facing the UK in 2024 and beyond.

The greatest glitch in progressive thinking has always been the belief that being right is enough; that the signalling of virtue alone is consequential (it isn’t).

There is no direction to history. There is only human agency and how it is deployed.

As the great writer said: we have got work to do.