Two elections have exposed the fractures and fault lines within France. There are many different visions of what the country is now and could be in the future, all of them seemingly irreconcilable with one another.

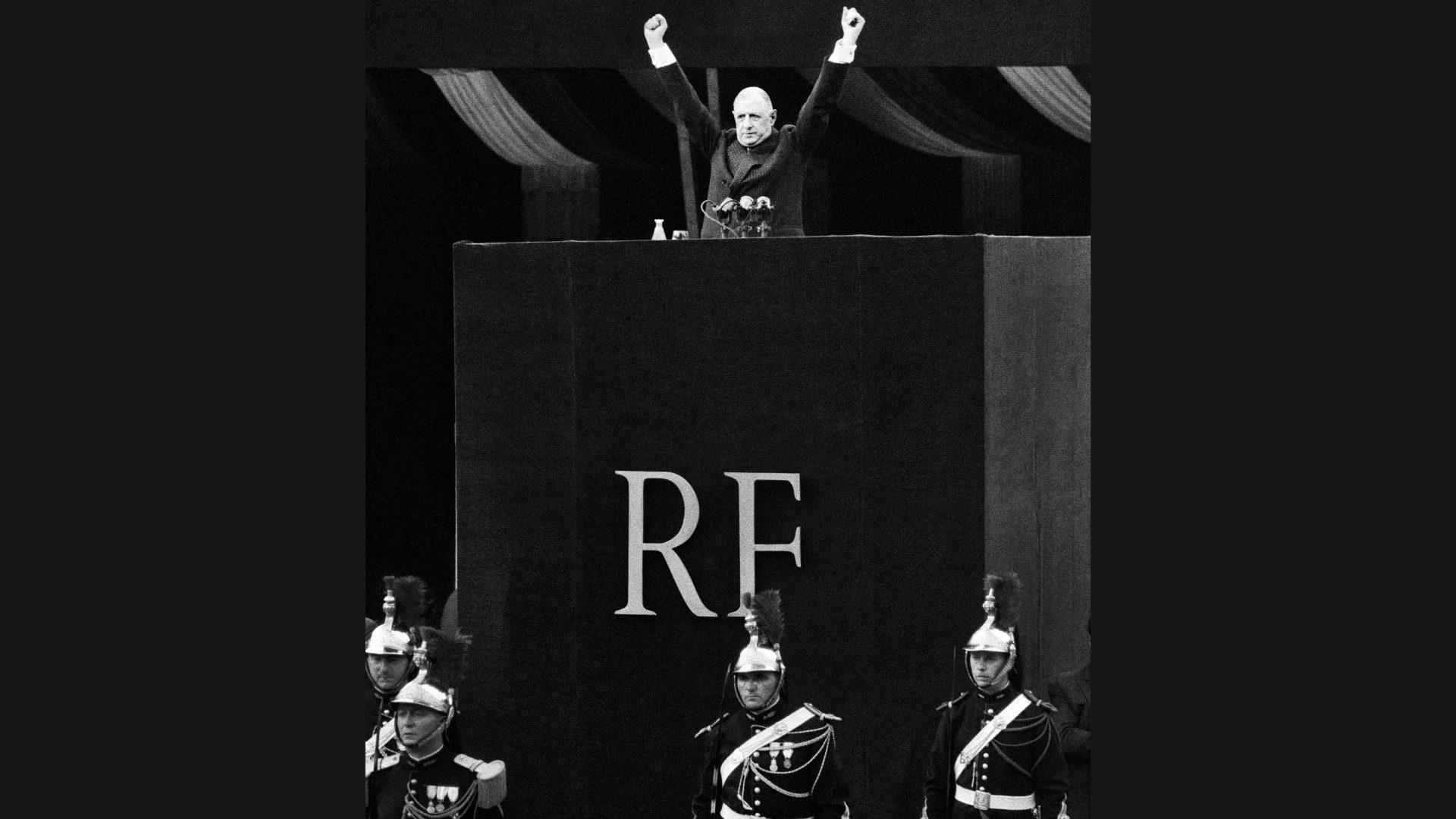

But as chaos rules where there once was stability, one thing unites the warring camps: Never have our leaders and would-be leaders invoked the spirit of General Charles de Gaulle as much as they have done in recent months.

Attempting to count all the election campaign references to “the man of Free France”, who died more than 50 years ago, can make you dizzy. Emmanuel Macron’s frequent references to de Gaulle have become a subject of mockery from pundits. Claiming a bond with the General is the equivalent of claiming to own a piece of the true cross.

What makes the spirit of de Gaulle so powerful to the French? Is it pure nostalgia for the days of dramatic parades on the Champs-Élysées and a time when the country’s defiant leader reflected and enhanced a sense of French exceptionalism? Or is there a desire for a new de Gaulle to emerge in an era where the nation is once again agitated by murderous upheavals and where the Franco-German relationship will be key to a reconstruction of Europe?

The desire for politicians to link themselves to de Gaulle can perhaps be understood thanks to the title of a book by Henri Guaino, former political adviser to Nicolas Sarkozy, the sixth president of the Fifth Republic: “de Gaulle, the name of everything we miss”. For the French, Charles de Gaulle is first and foremost la figure du recours – “The one we go looking for when things are going badly,” Guaino tells us.

France went looking for de Gaulle twice. Once in 1940, when the head of government, Marshal Pétain, decided to collaborate with the Nazi occupiers, and the General became leader of the Free French in exile. And again in 1958, 12 years after his resignation as head of the liberated country’s provisional government. Then, amid parliamentary stasis, generals plotted a coup d’état to keep Algeria, a colony in the grip of a deadly civil war, within French control. De Gaulle became president and, with his future prime minister Michel Debré, created the basis of a new constitution and the Fifth Republic.

The story of de Gaulle partly explains why, when they are finally beaten, France’s politicians are reluctant to leave the scene – as if even defeat contains a promise of victory. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Sarkozy and François Hollande have each, at the end of their term, cherished the hope of returning. They have all dreamed of being viewed as a person unjustly rejected but who has learned from his mistakes and who will do better next time. It has never worked for any of them.

The permanence of these figures does not help the renewal of the French political class. Instead, the “exes”, as they are called, serve to stifle competition. “Unlike in the United States, former presidents are not recognised as ‘wise men’,” notes French political pundit Jérôme Jaffré.

De Gaulle remains the one French leader widely recognised as someone who both dominated his time and who embodies the idea of France. So that what is called Gaullism “is not an ideology but a history”, according to Guaino.

De Gaulle redefined the country but he also fitted in with its mythology. The idea of L’Homme Providentiel (the Providential Man) – a dynamic hero of the masses – has become part of the French identity. This old monarchical country has always had its pantheon of saviours of the nation: from Joan of Arc to Napoleon, from kings to de Gaulle.

The idea of de Gaulle as Providential Man stems from the way that he took a country experiencing the upheavals of the Algerian war, a country not yet recovered from the Nazi occupation and its procession of “collaborators” and “resisters”, and popularised the notion of the unity of citizens rallying around “a certain idea of France”.

Yet the institutions of the Fifth Republic that he created with the new constitution of 1958 are built less for a Providential Man than for a monarch. Thanks to de Gaulle, the executive, and particularly the president, holds more power than in any other European country – unless, as in the case of Macron, he fumbles it.

Let’s play a game. Think of a power. The head of state has it. The French president can decide on the dissolution of parliament and organise referendums. He is the head of the army and has the ability to launch nuclear weapons. In the event of crisis, he can grant himself emergency powers for 30 days. He can pardon criminal convictions and he has an extended power of appointment. The king is dead, long live the king!

In the eyes of François Mitterrand, a resolute opponent of de Gaulle, this constitution and the exercise of power that results from it was nothing less than a “permanent coup d’état” – the title of the book that the future president was to publish in 1964.

Fast-forward to Sarkozy, elected in 2007, making his first presidential trip around France. On his return, dumbfounded, he confides to his relatives: “Incredible. The president is the king of France.” In 2018, the Gilets Jaunes confirmed the same idea, erecting cardboard guillotines on the roundabouts in reference to the execution of Louis XVI.

Everything stems from the head of state and everything is necessarily imputed to him. He is “the preeminent figure and the source of other powers”, according to Jaffré. Macron defends his method of governance by explaining that “when there are crises and wars, it is not illegitimate that many things go back” to the Élysée.

The general elections which took place on June 12 and 19 have shattered this principle. For the first time since 1965, a newly elected president has been denied the right to govern with a free hand. Macron’s MPs might be numerous but he has failed to reach the magic number of 289 MPs, warranting him the power to decide. Faced down by 131 MPs from the left-wing alliance NUPES (made up of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise, the socialists, Greens and Communists) and the 89 MPs from Marine Le Pen’s far-right Rassemblement national, Macron has to compromise with the only party left: the 64 neo-Gaullist Republicans.

France is going back to the multiple-party system that the General broke. Parliament will again become a place where backroom deals rule and the options include coalition, agreement on a case-by-case basis or stalemate and paralysis.

A page is being turned. Before these elections, where else, other than in France, could a head of state decide to send arms to a country at war yet to keep the line of communication open with the aggressor on the opposite side without ever debating it in parliament, much less submitting this policy to a vote of both houses?

Now absolute presidential power came to an end last week. Parliament has regained influence and strength.

During the pandemic, under the aegis of a health defence council bringing together a few ministers and senior officials, Macron decided on lockdowns, curfews or the lifting of restrictions, often freeing himself from the doctrines established by the scientists. This was at the cost of contorting the rule of law, even if debates in the National Assembly gave the illusion of deliberation.

Despite a constitution that establishes unprecedented presidential power, France and its presidents since 1958 have never installed an autocracy, let alone a dictatorship. There have been abuses of power: illegal phone tapping under Mitterrand, for example. But each of those who have risen to supreme power has imposed limits on themselves. It is as if the memory of the French Revolution and the fate reserved for the last king of France have shaped a “democratic superego”. This is not the least of the paradoxes of French governance.

In France, moreover, no president has won unanimous support during his lifetime, but each of them has sought to embody national unity. This “one and indivisible Republic”, as mentioned in the first article of the constitution, is therefore one with whoever is elected. The president is “a national referee”, according to the definition given by de Gaulle in his speech of September 4, 1958, with this consequence: he or she must continue to work for the legitimacy of power.

This legitimacy, believed de Gaulle, must never be taken for granted – even if in 1960, in a now-famous phrase, he had talked of “the national legitimacy that I embody”, and few would disagree with Jaffré’s insistence that “the legitimacy of the General, inherited from the war, was indisputable.”

While assuming almost supreme power for a seven-year term, he believed that the legitimacy of presidential control had to be given by the people, and so began a series of referendums intended to show that he continued to act in accordance with the aspirations of citizens. Within 10 years of taking power, de Gaulle had called five referendums. The election of the head of state by universal suffrage, a modification of the constitution ratified by referendum in 1962, made the exercise less necessary.

The idea that although the president’s powers make him part of a monarchical line, the real sovereign is the people, is undoubtedly one of the particularities of Gaullism. And it is a conviction that has often not been shared by his successors.

After the departure of the General in 1969, following the rejection of constitutional reforms in another referendum, politics took over. There have been other referendums, but each time, political ulterior motives have altered their spirit. A referendum has never again ended a leader’s rule, even when Jacques Chirac submitted the European constitution treaty to the vote in 2005 and “No” won by 55% to 45%. Chirac did not leave power, unlike de Gaulle, who found out he had lost at 8.01pm on April 27, had resolved to resign by 12.10am and made it formal at noon the next day.

Apart from the Providential Man indivisible from France, the other mythology of Gaullism is of The Man Who Says No. Experts have suggested that he often created crises to avoid others.

He said “no” to the collaboration of Pétain in 1940, “no” to the Common Agricultural Policy via the strategy of the empty chair in Europe in 1965, and “no” to Nato’s integrated military command in 1966. Chirac’s “no” to the war in Iraq launched by the US of George W Bush in 2003 is described as a “Gaullian moment”.

Many have tried to seize the mythology of the Man Who Says No, including Éric Zemmour during the last presidential campaign. The former journalist made saying “no” to what he classed as the disappearance of France due to massive immigration the centrepiece of his strategy. A video announcing his candidacy clip went so far as to imitate the June 18, 1940 appeal made by de Gaulle from London on the airwaves of the BBC, urging the French to resist the Nazi occupiers. It showed Zemmour in front of an antique microphone against the backdrop of a library. But Zemmour’s long-held sympathies for Marshal Pétain collided with this claim to be a child of de Gaulle.

The Gaullian “no” to control from elsewhere reaffirms the notion that sovereignty and the nation can only belong to the people. References to the balance between the authority of the state and the agreement of the people are almost obligatory in presidential speeches. France is a nation-state which, from Bonaparte to de Gaulle, “was first embodied in the king and which is now embodied in the people”, notes Guaino. This is part of French exceptionalism. But to be exceptional, you must be among the great nations of the world.

This was not the least of de Gaulle’s challenges when he came back to power in 1958. Inflation was 16%, industrial production was down and the foreign trade deficit had reached record highs. De Gaulle responded by resolving to put France at the apex of innovation and technological progress. Two years later, highways, land use planning and economic planning were being revolutionised and the country’s research budget had been multiplied by three, notably by creating the Centre for Space Studies. “There is an obsession with national independence in this career soldier,” Patrice Duhamel, the writer, screenwriter and journalist has said, “and a proud conception of France’s place in the world.”

France was being modernised. But how could an average power impose itself on the international scene? How could a country defeated in the second world war sit on the UN security council and enjoy there, like the US or Russia, a right of veto? In 1960, de Gaulle decided to create the French nuclear deterrent force while founding an army capable of fulfilling all missions.

With these cards in hand, France could maintain its rank and its determination to speak loudly on the world stage. The “French arrogance” often denounced in particular by the Anglo-Saxon world lies in this will to act independently, including from allies and partners. As de Gaulle said, “one can be great even without a lot of means”.

Macron promised major reform after his re-election: on green issues, on the economy, on the welfare system. First inflation, the war in Ukraine and the consequences of the pandemic denied him any budgetary room for manoeuvre and now parliament will question everything. It is as well that Macron has heeded one of the lessons of de Gaulle: a revolt against fatalism. The General’s famous maxim “Where there is a will, there is a way” is likely to become a key phrase in his fight against what he calls the “sad passions” of decline, defiance and demagogy.

The National Assembly, born of the June general elections, will challenge Macron’s resolve. Compose, collaborate, negotiate: this will be the task of the government. It is a huge challenge in a country whose culture and nature is not naturally compromising.

The election result itself has undermined the Gaullist principles of political architecture. Macron must now prove to the French that the institutions will hold and that he will not be a lame duck head of state. Macron has long dreamed of himself as de Gaulle, it is up to him now to show real political genius, and not just a talent for tactics.

And this will not be the least of the difficulties for Macron, operating in a context of mistrust and anger rarely encountered in the past 20 years.

De Gaulle’s constitution established a duo at the head of the executive: the president and his prime minister. Under the terms of article 20 of the constitution, the prime minister leads the government and “determines and conducts the policy of the nation”. Jaffré notes that “de Gaulle said that the president is in charge of the crucial issues. He is therefore not in charge of the incidental or the daily questions”. Duhamel notes that “the General was the least omnipresent of the eight heads of state of the Fifth Republic, but the most sovereign of the eight”.

Over 64 years, the two heads of the executive have developed unique relationships. The prime minister is sometimes a “collaborator” (according to Sarkozy), a rival (there are examples galore), a subordinate or an opponent (when there is a ‘cohabitation’ between a president and a PM from rival parties). Some question if the importance of the prime minister is gradually disappearing over time.

With Macron, the question does not arise. He does everything, his prime ministers the rest. Power is not shared. And when the prime minister tries to achieve some degree of autonomy, he is at best ignored, most often fired. This is what happened to the prime minister of Macron’s first five-year term.

With a new political situation, never before encountered, will the newly appointed prime minister Élisabeth Borne be up to the challenge? She is often said to be a technician and not a politician. Though she has come from the left, her achievements have included reforming the national railway company against union pressure and cutting unemployment benefits. She is a tough negotiator and a hard-working minister.

But is she prepared for months of parliamentary filibustering? Is she the sure hand needed to negotiate, day-by-day, majorities on crucial laws regarding the cost of living, and many other things? Far-right and far-left MPs will be at her door demanding more money for the poor and the forgotten while the traditional right will underline the fragile state of the French budget and the frightening level of the national debt (115% of GDP).

Macron has always based his own political philosophy on being of the “right and left at the same time”. It’s a formulation intended to show his willingness to erase partisan reflexes in the name of the higher interests of the nation. Is this a lesson learned from the founder of the Fifth Republic? The definition of Gaullism, according to the writer André Malraux, the General’s iconic minister of culture, is representing “the subway at five o’clock in the evening”. In other words, overcoming political divisions for the best interests of all the French.

This is what Macron is calling for now. But his opponents are not listening, because they are too busy smirking. The president has come to terms with reality: nobody (for the moment) is ready to help him out. French voters have created a political catch-22 situation.

Maybe it will come easy to him. After all, many of those who claim to be de Gaulle’s heirs have always said the Macronian “at the same time” is just about political bargaining and not about the spirit of the General. “He would never question whether a measure was tagged right or left, just whether it was right or wrong,” they say.

Meanwhile, is the Fifth Republic that de Gaulle created now dead? If Macron cannot build a coalition with the Republicans, he will have to find majority support for some of his plans. This will not only be hard work but is likely to be unpopular with the French public.

The third and most radical solution is to call for new general elections. This would be a dangerous plan for a man who polls show is disliked by 70% of France. If asked again, they might give him the sack for good.

In Brussels last week, Macron called the pickle that he is in “an awfully common situation”, given that 19 of the EU’s 27 countries are currently led by coalitions.

He might as well have signalled the end of the era of France’s almighty heads of state. Whatever would de Gaulle think?

Valérie Nataf is a broadcaster for the French TV station TF1