The staff of the Washington Post have finally discovered why Jeff Bezos hired Will Lewis as their CEO and publisher. He will carry out the boss’s orders, no matter how outrageous they are.

The Post’s own reporting has made it alarmingly clear that if Donald Trump gets a second term he could in one week blow up 240 years of work on the American project. With 11 days to go before the most consequential presidential election of the century, the editors had drafted an endorsement of Kamala Harris for president.

Then Lewis, a 55-year-old Londoner who was once editor of the Daily Telegraph, delivered the orders: the boss wanted to end the practice of editorial endorsements. There would be no space in the paper to explain why Harris had to be by far the clearest choice.

It was quickly reported that Bezos had ordered the block, and that Lewis had pleaded with him to change his mind, but to no avail. Embarrassingly, Lewis had to come and insist that this version of events was untrue, and that Bezos “was not sent, did not read and did not opine on any draft.”

Lewis added: “As publisher, I do not believe in presidential endorsements. We are an independent newspaper and should support our readers’ ability to make up their own minds.” Few in the US media world are buying this version of events, and criticism of the Post’s decision continues to grow.

The legendary reporting team of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein said, in a joint statement: “Under Jeff Bezos’s ownership the Washington Post has used its abundant resources to rigorously investigate the danger and damage a second Trump presidency could cause to the future of American democracy and that makes this decision even more surprising and disappointing especially this late in the electoral process.”

As generous as Bezos had been with the editorial budget, he apparently had his limits when it came to his own business interests, which include lucrative government contracts. Trump believes in retribution against those who cross him. Bezos apparently felt that, were Trump re-elected, an endorsement for Harris would put him in line for punishment.

This was a theme picked up by former Post editor at large Robert Kagan, who resigned from the paper shortly after Lewis’s announcement. He called Bezos’s move a straight “quid pro quo” and noted that Trump had met representatives of the Amazon founder’s space company Blue Origin shortly after Lewis’s bombshell announcement.

“Trump waited to make sure that Bezos did what he said he was going to do, and then met with the Blue Origin people,” Kagan told the Daily Beast. “Which tells us that there was an actual deal made, meaning that Bezos communicated, or through his people, communicated directly with Trump, and they set up this quid pro quo.”

Eighteen Post columnists also registered their revulsion for the endorsement spiking in an open letter that Lewis and Bezos did allow the Post to publish. “The Washington Post’s decision not to make an endorsement in the presidential campaign is a terrible mistake,” it began. “It represents an abandonment of the fundamental editorial convictions of the newspaper that we love.”

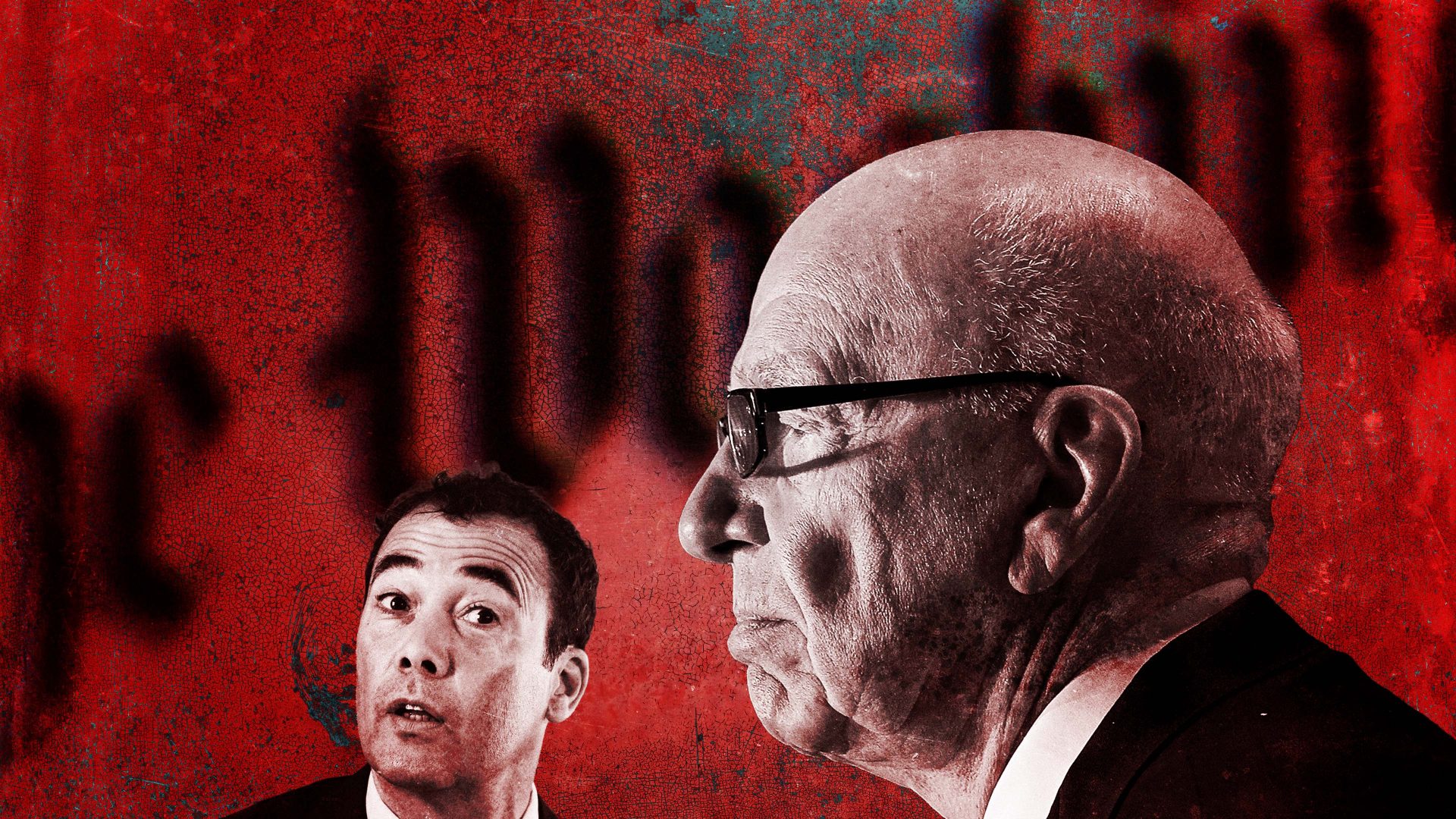

The endorsement debacle marks a new low in relations between Lewis and the Post’s staff, who have been in revolt against him since Bezos hired him a year ago. Until now, most of the concerns were about the Brit’s past history working for another billionaire, Rupert Murdoch.

As more and more emerges about the depravity of the Murdoch tabloid newsrooms during and after the exposure of their criminal hacking operations – thanks largely to litigation in the High Court led by Prince Harry – Lewis has become pursued by questions about the role he played at the Murdoch papers from 2010 to 2012. This has taken on a new gravity as a result of action taken by the former Labour prime minister, Gordon Brown.

Brown asked Scotland Yard to review evidence that would, he believes, lead to a criminal prosecution of Murdoch executives. He charged that Murdoch-directed hackers reverse engineered his phone number, faked his voice to secure personal information from his lawyer, paid an investigator to break into the police national computer searching for personal information about him and accessed his medical records.

Brown specifically zeroed in on Lewis, alleging that he was a key accomplice in an operation to destroy evidence contained in emails and computer hard drives at the Murdoch headquarters in Wapping, east London: “While Lewis has always claimed he was Mr Clean Up, these new allegations point to a cover-up. The destroyed emails were likely to have revealed much more of News Group’s intrusion into the private lives of thousands of innocent people…”

Lewis has adopted a bunker mentality in dealing with his past. His spokesperson at the Post repeatedly says he has a policy of not responding to the claimants’ allegations, a policy repeated when I requested a response to Gordon Brown’s accusations.

He certainly has his hands full at the Post. He was hired by Bezos in November,2023, a year in which the paper lost $77m in 2023. Reader subscriptions, web traffic and digital advertising were in freefall.

As Lewis looked at the grim figures, a nervous staff were assessing his credentials. His record in New York as CEO of Dow Jones, publisher of the Wall Street Journal, promised a hardened pro, but little was known of his time at Wapping. The hacking scandal seemed old news.

But then closer examination revealed that he was a major target of Prince Harry’s lawyers, suggesting that he bore the stigma of the worst side of British journalism, not the best. He rebutted that view to the Post staff, saying “I did whatever I could to preserve journalistic integrity” – a position he has sustained since then, despite it becoming less and less convincing.

At the same time he scolded his newsroom: “People are not reading your stuff.” The tension grew between Lewis and a staff pledged to the highest standards of editorial independence under the rubric of “Democracy dies in darkness” – a slogan that now seems bizarre given that he and Bezos have turned off the lights with their capitulation to Trump.

Nevertheless, Lewis pressed ahead with a new strategy including the creation of a “third newsroom” that would create content driven by social media, to sit alongside the traditional division of news and opinion. Executive editor Sally Buzbee, sidelined in the changes, left.

Lewis likes bringing in wing men from his previous jobs. Buzbee was replaced by Matt Murray, from the Wall Street Journal. Lewis announced that he would be followed, after the November presidential election, by Rob Winnett, a former colleague at the Daily Telegraph in London and virtually unknown in the US.

With that move, Lewis triggered a deeper look at his old associations in London and the whole plan blew up in his face.

His own reporters at the Post uncovered a connection between Winnett and John Ford, a self-confessed journalistic “blagger” who has admitted using illegal methods to obtain information used in stories at the Sunday Times, where Winnett and Lewis both worked before joining the Telegraph. The New York Times made the story more radioactive by locating a former Sunday Times reporter who claimed that while they were at the paper Lewis and Winnett had used the same methods to get phone and company records for stories.

Winnett withdrew from the appointment. Now, as the Post covers one of the most consequential presidential elections in history, it remains distracted by itself being the subject of investigations by other reporters that lead back to their publisher’s career on the other side of the Atlantic some fourteen years ago.

The story of the first months of Lewis’s career with Murdoch reads like a rite of passage in which he set out to prove himself, in the Sicilian sense, as a Murdoch “made man.”.

He arrived in Wapping as general manager of the newspapers in September, 2010. He was actually hired in July, and was subsequently briefed on what his priorities should be by the CEO of News International, Rebekah Brooks. (A spokesperson for Brooks confirmed to me that Lewis reported directly to her but would not discuss whether James Murdoch, Rupert Murdoch’s younger son, who was the executive chairman of the newspaper group, or his father, were involved in hiring Lewis. With an appointment at that level it would have been unusual if they were not.)

Up to that point, Lewis had an ascendant reputation as an editor, appointed as the youngest ever editor of the Telegraph in 2006, who had dragged the paper from its fustian past into the digital age. The paper also had a memorable scoop, exposing the widespread abuse of what members of parliament charged as expenses.

Lewis was drawn into the orbit of Boris Johnson, then the mayor of London, gratifying Johnson’s profligacy by hiring him as a columnist, at five thousand pounds a column. When this was attacked for being obscenely generous, Johnson replied that, for him, it was “chicken feed.”

It was an odd pairing of personalities. Lewis’s brand was being the modernising force, an unprivileged meritocrat shaking up a paper that had been run by toffs, like the high Tory Charles Moore. He was directing the Telegraph to be more appealing to people like him, not born into the Tory tribe but who elected to join it on the way up in a career.

Lewis was captured by the Boris bandwagon, hitching a ride on it as a political opening for himself, having no problems with Johnson’s mendacity or rule-mocking social habits. That choice came to a dead end when Johnson resigned after the Partygate scandal, but Lewis eagerly accepted a knighthood in Johnson’s resignation honours list (in itself something of an oxymoron).

Now, as a manager in Wapping, he was empowered to see the business as a whole, and he found a place under siege. For months top executives had been scrambling to contain the damage done by the exposure by one reporter, Nick Davies of The Guardian, of industrial-scale hacking at Murdoch’s Sunday tabloid, the News of the World.

It is not disputed that the Wapping IT system was overloaded and frequently crashed. Lewis’s defence of his actions is based on this chaos – that far from deleting millions of emails, as the claimants in the Harry-led case allege, he was trying to “migrate” emails from failing servers to a new and more stable system while, at the same time, the company was moving to new offices.

Adding to the pressure by the end of 2010, two groups of investigators were about to arrive in Wapping, a group of Members of Parliament and detectives from the Metropolitan Police.

Lewis himself did not have the technical skills necessary to fix the crisis. To do so, he hired two former colleagues at the Telegraph. The most experienced, Paul Cheesbrough, who had earlier in his career played a key role in the BBC’s transition to digital platforms, was appointed as director of IT services, along with Jim Robinson, who became head of desktop services.

Whatever the truth about the disappeared emails, it turned out later that an outside contractor, Essential Computing, who managed the systems, had backed-up a large part of both the live and archive materials. More than 21 million emails were recovered and handed over to the police. Nobody will ever know what was in the nine million that were deleted and never recovered.

So far, the hacking scandal itself hadn’t aroused a broad public concern. A cynical view was that it was a war about journalistic ethics being conducted between two sides of Fleet Street, the tabloids – including the Daily Mirror and the Daily Mail – and The Guardian. The average punter shrugged it off in the phrase “it’s what they do, it’s what they are, isn’t it?”

Then it all changed. In June, 2011. Davies reported that in 2002 the News of the World had hacked the voicemail of Milly Dowler, a 12-year-old schoolgirl, six days after she had gone missing – she had, in fact, been murdered and her body was found six months later. This was so repugnant that it provoked a world-wide reaction and, more concerning to the Murdochs, a political backlash.

Their first response was to make the poachers look more convincing as gamekeepers. Rupert Murdoch announced the formation of a Management Standards Committee, on which Lewis had a key role, to oversee the collection of evidence.

Lawyers for the 40 claimants in the Prince Harry led case are critical of the result, naming Lewis as one of the executive members who “deliberately failed to fulfil its stated commitment to cooperate with the Members of Parliament and participated in the strategy of concealing and destroying evidence.”

Those 40 claimants are the fourth and final wave of hacking victims to take legal action against the Murdoch tabloids (News Group Newspapers has persistently denied that hacking took place at The Sun as well as the News of the World, although it has settled cases involving The Sun.). The previous waves resulted in a total of 1,300 cases being settled by NGN. According to a source with knowledge of the settlements, that has come at a total cost so far, including legal fees, of 1.9 billion pounds. The largest individual settlement went to Hugh Grant, who said it was so huge that it was an offer he couldn’t refuse.

In assessing Lewis’s role it’s important to recognize that damage control resulting from the hacking was not his only focus as soon as he arrived at Wapping.

Rupert and James Murdoch had another urgent concern. They were asking government regulators to allow them to take majority control of the TV satellite broadcaster BSkyB.

In 1984 Murdoch had taken a costly gamble by pioneering satellite broadcasting with Sky Television, a gamble that finally paid off in 1990 with a merger with British Satellite Broadcasting. The move for full control in 2011 was fiercely opposed by prominent politicians and rival media owners because of how, together with his newspapers, it would have significantly enlarged Murdoch’s media influence in Britain.

James Murdoch, then regarded as the likeliest successor to his father, was proud of Rupert’s nerve in making big bets on the future. Although James’s role in Wapping obliged him to engage in what was, to him, the grubby netherworld of the tabloids, he had a more strategic view. In terms of the Murdoch empire as a global whole, he saw the tabloids as the past, not the future. And he was at one with his father’s view of public broadcasting as an unfairly subsidised competitor and that meant in particular the BBC – as he put it in a keynote 2009 lecture – “the scope and ambition of its activities and ambitions is chilling.”

The Tory-Lib Dem coalition government under David Cameron was divided over the bid. The Lib Dem business secretary, Vince Cable, was known to be opposed, while Tory ministers were ready to give Murdoch majority control (at that point he had a 39 percent holding).

The Murdochs wanted to flush out Cable’s bias and remove his influence. By pure chance, Lewis obliged. He was tipped off by an editor at the Telegraph that two of the paper’s reporters had covertly taped a conversation with Cable in which he said “I am at war with the Murdochs.”

The Telegraph sat on the story because its owners were opposed to the Murdoch bid. One of Lewis’s longtime friends was Robert Peston, a BBC business reporter. Lewis passed the Cable tape to him and – ironically in view of Murdoch’s loathing of the BBC – Peston’s airing of the Cable comment ended Cable’s hope of stopping the bid. Cameron switched oversight to the culture minister, Jeremy Hunt, who was disposed to approve it.

Lewis has cited the confidentiality of a source in refusing to confirm that he passed the tape to Peston. However, according to new evidence presented to the court by Prince Harry’s lawyers, it was Lewis’s second hire from the Telegraph, Robinson, who acquired the Telegraph tape and gave it to Lewis who then leaked it to Peston.

As things turned out, the Milly Dowler hacking and the public response to it made it impossible for the Cameron government to approve the bid. The Murdochs withdrew it. Eventually BSkyB, once more as Sky Television, ended up as part of the American NBC television empire.

(This year there was a new twist to the Dowler story. Glen Mulcaire, a private investigator jailed for six months in 2007 as a result of the hacking of phones used by members of the royal family, claims in a personal memoir, Shadow Man, that a News of the World reporter first hacked the Dowler phone and then asked him to repeat it, so that if it was discovered he would take the blame, which happened in 2014 when Mulcaire was given a six month suspended sentence.)

Lewis left the Murdoch fold in 2020, after six years at the Wall Street Journal. Robert Thomson, chief executive of News Corp and a long-time Murdoch consiglieri, said that Lewis “has overseen a remarkable period of growth and digital transformation.” Staffers remember him not for any journalistic brilliance but for his zeal in cutting costs.

Paul Cheesbrough, Lewis’s sidekick at Wapping, remains a Murdoch man and has outshone his patron, rising rapidly on his own merits as a digital-savvy rainmaker. He moved to New York as Chief Technology Officer for the Fox Corporation. He is now CEO of Tubi Media, a booming spin-off in California, based on advertising-supported streaming. He reports directly to Lachlan Murdoch.

Meanwhile, new allegations made by Prince Harry’s lawyers include a boggling picture of the scale and duration of the use of private investigators by the Murdoch executives, not just newsroom hacking for scoops on the private lives of celebrities but to pursue politicians deemed hostile to the interests of the Murdoch empire – this even included politicians participating in the 2011 Leveson Inquiry into press ethics (which, it has to be said, had minimal effect on the ethics of the tabloids).

The Murdoch lawyers told Leveson that between 2005 and 2011 the papers had spent a total of 30,474 pounds on private investigators. The latest tranche of papers submitted to the High Court includes an audit of the accounts of twelve PI contractors. It shows that just one contractor alone received 323,286 pounds during that period. In fact, the Murdoch organisation spent well over a million pounds on PIs in that time and the audit comments that the version given to Leveson was “grossly misleading.”

In a response to me a News UK spokesperson did not deny that total. But they claimed that the number submitted to Leveson related “only to private investigators.” This excluded “enquiry or search agents” defined as individuals or agencies that “check publicly available records and databases” and that the figure cited in the court papers includes both.

This seems disingenuous. If it was so, the Murdoch editors spent a great deal of money hiring people to do searches that would normally be the work of journalists.

Although it is Lewis who has so far taken the heat for the cover-up allegations he did, after all, work directly for Rebekah Brooks. And she, in turn, reported to James Murdoch. Prince Harry’s lawyers describe Brooks as a “controlling mind” of the newspapers. In the only criminal trial resulting from the hacking, at the Old Bailey in 2014, Brooks was found not guilty on a charge of acting to pervert the course of justice.

A basic part of the Murdoch lawyers’ defence against the claimants’ allegations is that as far as proof of wrongdoing is concerned the clock stopped with that trial and verdict. For example, in responding to me about Gordon Brown’s new action a spokesperson said, “The evidence Mr Brown refers to is not new and has already been the subject of considerable scrutiny including a lengthy and extensive police investigation from 2011-2015 and at a criminal trial. His assertion is highly partial and quite simply wrong.”

This seems wilfully to ignore the fact that several years of discovery by the claimants’ lawyers have amassed a far more detailed narrative than the original police investigation that led to the Old Bailey trial. A source familiar with that discovery process told me that there are thousands of pages of witness statements not yet disclosed in the court papers – and it is important to bear in mind that the court submissions are synoptic summaries of allegations, and do not include the supporting evidence.

All that would spill into public view if the trial goes ahead as scheduled in January, something that neither the Murdochs nor Lewis can want. The Murdoch lawyers have until 4pm on January 7, three working days before trial, to agree on the list of evidence submitted by the claimants.

Whether it goes that far depends on whether Prince Harry and the other claimants receive an offer they can’t refuse. The Duke of Sussex has deep pockets and a steely resolve based on years of hostile coverage by the tabloids. As yet he shows no sign of settling.

British journalists have a long record of achievement working in America, and still do. For example, John Micklethwait who is editor-in-chief of Bloomberg News, or Mark Thompson, who after skillfully managing the transition of the New York Times from print to digital is now running CNN.

Will Lewis is not adding to that reputation. Instead, he is showing how much he learned at the feet of Rupert Murdoch. Indeed, his faithful execution of Bezos’s gag order, essentially the suppression of the Post’s collective editorial voice, removes any lingering ambiguity about his loyalties.

So far, that does not imply any proprietorial influence on the newsroom. But it must be unnerving for any reporter to know that your publisher doesn’t necessarily have your back.

Eugene Meyer, a very wealthy man, bought the Post at a bankruptcy auction in 1933 for $825,000. He told the staff that their job was to “tell the truth as nearly as the truth can be ascertained” and added: “In the pursuit of truth, the newspaper shall be prepared to make sacrifices of its material fortunes, if such a course be necessary for the public good.”

In 1972, when Meyer’s daughter, Katharine Graham, was publisher, Woodward and Bernstein were the only reporters seriously pursuing the Watergate story. Bernstein called Richard Nixon’s attorney general, John Mitchell, to check the facts of a story about to be published. Mitchell blew up and rasped, “Katie Graham’s gonna get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.”

The White House continually put pressure on Graham and her editor, Ben Bradlee, to call off the two reporters, to no avail. In 1974 Nixon resigned as president, as a direct result of the Post’s reporting. Mitchell went to jail.

Make no mistake, things are different now. Jeff Bezos does care about “material fortunes.”

Clive Irving, a former managing editor of the Sunday Times, is a contributor to titles including Vanity Fair and is the author of The Last Queen