Once upon a time a young Argentinian PhD student – me – came to London and wished she had enough money to see all the plays the capital had to offer. Fast forward a few short years, she now has more money, but there is much less to see. Is it the fault of Covid-19, or perhaps of levelling up?

On my way to the National Theatre to see Federico García Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba, in a reworked version by Alice Birch, I struck up conversation with a Good Samaritan who helped me navigate the Northern Line at Euston. When I told him where I was now living, he looked at me with a mixture of pity and surprise: “Sheffield, of all places?” So much for levelling up.

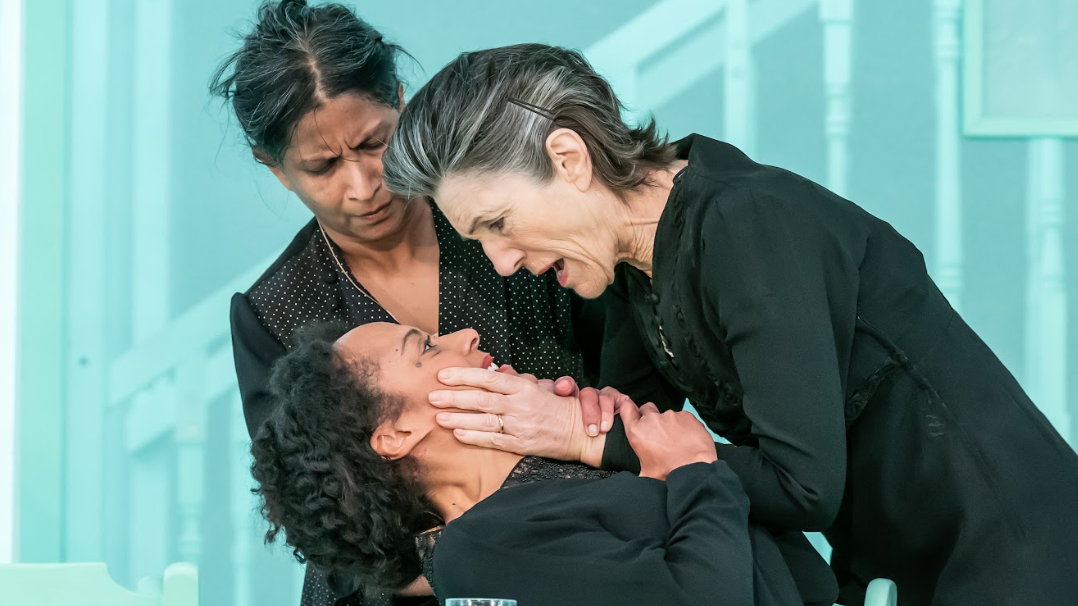

I arrived at the theatre seconds before the curtain went up. My heart was pumping not just because I was late, but also because I was excited to see Harriet Walter on the stage for the first time in one of the great female roles of western theatre: Bernarda Alba. After the death of her second husband, the tyrannical widow imposes eight years of mourning on her five daughters, aged between 20 and 39.

The play is too often reduced to cliches about Spain, with its representation of an outdated kind of ultraconservatism. But as you watch, it must be remembered that not long after the play was completed came the coup against the democratic government, and shortly after that García Lorca’s execution.

It was refreshing to see Birch address more universal themes of intergenerational conflict and inheritance. Sounds familiar? Well, it certainly will to the many fans of Succession, for which Birch won the 2020 Writers Guild of America Award.

Perhaps it was the association with Succession that meant the audience came with odd preconceptions. So – spoiler alert – when Bernarda Alba took out a rifle to shoot her youngest daughter’s lover, why did the audience laugh? At other points in the play it was refreshing to experience the often-neglected humour of Lorca’s plays, but the ending is meant to be anything but humorous.

A school production in Buenos Aires of The House of Bernarda Alba was the very first play I ever saw, and I still recall the shiver brought on by the final moments. But in London, all the murder and suicide left me cold. Something had gone seriously awry.

The gorgeous green set-design is remarkable: the audience can see all the different rooms of the house, and the principal action is complemented by whatever other characters are doing elsewhere. We see a more fragile side to Bernarda, the mother, in private, as she strokes a sleeping daughter or tends to her demented mother.

There were moments of high visual intensity, such as when a mob takes the house by storm, but on press night several moments of synchronised coughing in the audience were an unmistakable sign that the crowd was not following the action. During the interval I heard one woman ask her friend, “So who is whose daughter?”

Wandering confused out of the auditorium I struggled to make sense of what I had seen. I was feeling a little dazed, and perhaps that’s why I inadvertently stumbled into an area cordoned off for a private party, and wondered if my press ticket gave me access.

I would have liked to have talked it over with some of the crowd, and perhaps got stuck into some of the complementary bubbly. But that would have meant spending £200-plus on a hotel – and so the last train to Sheffield beckoned.