It’s easy to look at the UK and think it can’t get anything done: we have dismal economic growth, we can’t build train lines and we certainly can’t build enough homes. But for those losing hope in British creativity and industry, there is at least one thing we are good at: creating endless new explanations as to why we shouldn’t be building more homes, actually.

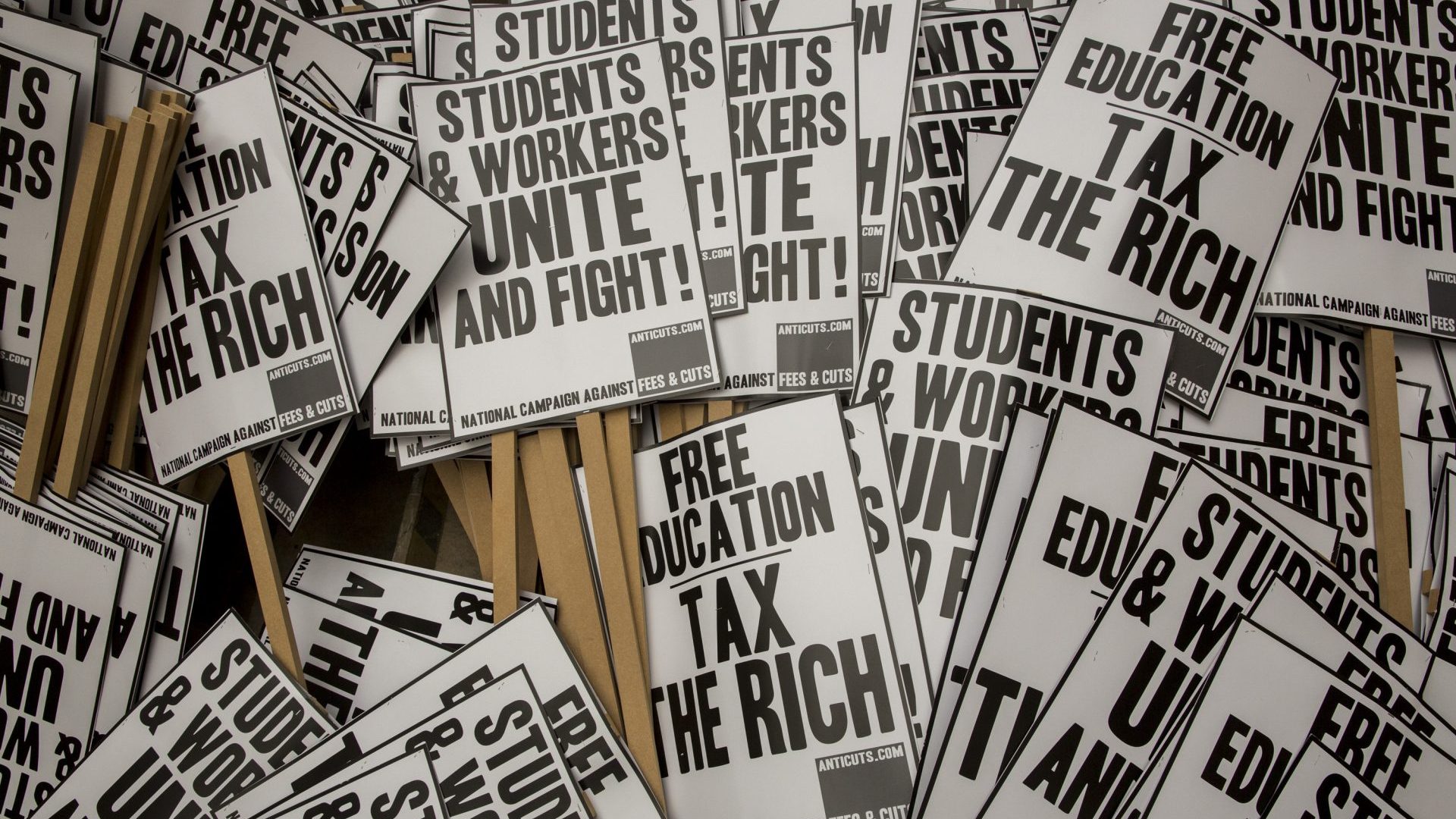

One of the best Nimby tricks is presenting the idea that we should continue tolerating the existing dismal housing situation as somehow progressive. This conjuring trick should be impossible, but it is made much easier by tapping into the hard left’s need for every social issue to have an obvious villain.

The latest in a long line of left-Nimby arguments appeared in the Guardian last month, offering up a “surprisingly simple solution to the UK housing crisis”, which was to abolish landlords. Dismissing questions of supply as a “fruitless debate”, the article said the UK had enough homes, but they were distributed badly.

Let us return to the issue of landlords later, as it is largely irrelevant to the truth of the matter. Whenever you see an article arguing that the UK has enough homes, from someone of any political persuasion, you can be sure you’re going to see some misunderstood statistics, or figures used incorrectly.

This one was no exception, citing every Yimby’s least favourite measure: that there are more homes than households in the UK, which is inevitably used to argue that there are enough homes to go around. People deploy this figure in supposedly serious arguments, despite the fact that a toddler should be able to see the problem with it.

Definitionally, you cannot be a “household” without already having a home. So if there is a single empty home in the whole country – whether it’s being demolished, is in probate, is a holiday lease, or for some other reason – there will be more homes than households. It is quite literally impossible for there not to be more homes than households.

It gets worse: the definition of “household” in the UK is an expansive one. Let’s imagine you have a flatshare of five people in London, each of whom would rather live on their own. Those five people count as one household, but if they could afford to live according to their actual preference, they would be five.

To point to the homes versus households numbers and say they show there isn’t a supply problem is to fundamentally misunderstand the very basics. Obviously, though, no good disingenuous housing argument is complete without suggesting that the real issue isn’t that there aren’t enough homes, but to say that it is the nature of who owns them that is the issue – which is then typically backed up by cherry-picking some statistics from Europe.

On this, the Guardian did not disappoint. Vienna being “so much more liveable” than London is

proof “landlordism is holding us

back” by driving up prices, inflating land values and preventing the “decommodification” of homes. Except, as @IronEconomist noted on X, there is something else going on in Vienna and Austria as a whole: they build far, far more houses than we do and have done so for decades.

Austria as a whole builds around three times as many houses a year relative to its population – meaning if the UK built at the same rate as Austria, we would be building 630,000 homes a year, rather than the 200,000 we put up at the moment. Vienna builds homes at roughly twice the rate of London, and has done so for years.

Whatever metric you look at shows that the UK’s problem is supply: our vacancy rate for rental properties is one of the lowest in the world, which gives landlords no incentive to drop prices, and little incentive to improve properties or even do basic repairs.

In other words, articles blaming landlords for the UK’s housing issues have the issue backwards – the UK’s landlords are as bad as they are because supply is so constrained. Fix the latter and you’ll fix the former. Trying to tackle landlords without boosting supply is guaranteed to have unintended consequences.

George Orwell controversially said the worst landlord was the “poor old lady” who lived in one slum house and leased out another two as her pension – because she could never afford repairs. This remains somewhat true in modern Britain, but social landlords are often as bad – their institutional finances are stretched, and their tenants have no alternatives, being priced out of the private sector and knowing that waiting lists are years long for social homes.

Trying to force transfers from private landlords to social landlords would lead to years of costly court battles, and wouldn’t change the fundamentals.

It is not as if “banning landlords” hasn’t been tried: Rotterdam recently attempted to do just that, in about as tough a fashion as you could manage without a government simply taking command of the housing sector entirely (which no UK party, including the Greens, is even close to proposing).

Rotterdam made it so that anyone buying a home in the city could not lease it out for at least four years afterwards – in effect removing all investment buyers, as leaving a property empty for four years is too costly for anyone to absorb.

Given that anti-landlord sentiment in Rotterdam is even more intense than in London, the move was in line with popular sentiment, but its results were predictable: the richer renters who could look to buy a property at a slight knock-down from existing prices benefitted, to an extent, with an uptick in first-time buyers.

But there were still an average of 120 people chasing each new rental property, and now there was no new supply and existing rental properties were disappearing from the market – meaning at the lower price brackets, properties became impossible to get.

By contrast, a New Zealand scheme that focused on boosting housing supply without worrying about who owned what actually delivered more new homes and – crucially – lower rents. Supply is what breaks the cycle, even if Rotterdam is stubbornly insisting on proving this solely by trying every other approach first – it is now sampling rent controls, too.

None of this is to say landlords are good, or to rule out taking action against them. The UK can and should improve tenants’ rights now: giving more rights to modify your home, longer leases with capped rent increases, the right to a pet, better rules on wear and tear, and more. Tax on property, like other wealth, should be higher. We need redistribution for any hope of social mobility in Britain.

What we can’t keep doing is pretending that a “surprisingly simple” trick will help the UK’s housing situation. If you want more homes, build more homes. That might sound simple, but we have failed at it for 30 years and if we keep failing, homes will stay unaffordable (even to rent, let alone to buy).

Blaming landlords is satisfying because it gives an easy villain and an easy fix, a world in which we might somehow have cheap homes quickly. But that is the false hope of populism – and false hope is worse than no hope. Build more bloody houses, and ignore anyone who says we don’t need to.