Autobiography should be the easiest thing in the world to write. You sit down and bash out the one story you know better than any other: your own. I mean, how hard can it be?

Yet autobiography is surprisingly easy to get wrong. What do you include? What do you leave out? Anecdotes you consider to be solid gold and people that are fascinating to you might not prove even mildly diverting to your reader.

Bad autobiographies fall into two broad categories. There is the turgid, ghostwritten memoir meticulously combed to remove any hint of controversy or even opinion. Footballers are among the worst culprits, a dressing room omertà on bean-spilling leading to 90,000 words of “obviously the lads were disappointed but we put it behind us and moved on”.

Then there is the self-righteous justification of a colossal ego, authors who see the writing of their story as the long-awaited opportunity to wang on without interruption, settling scores, having last laughs, rehashing tired anecdotes, avenging ancient slights real or imagined and ignoring inconvenient truths to become the untarnished heroes of their own lives.

What might be a cathartic voyage into I-told-you-so for the author, however, can be for the reader like being buttonholed at the world’s longest party by the world’s most colossal bore. I have read plenty of these. Only two have managed to plumb all those negatives yet somehow remain a thoroughly enjoyable read.

The first was Bruce Forsyth’s Bruce, a riproaring voyage around the entire circumference of the entertainer’s impressively colossal self-regard that works because he actually was as good as he thought he was.

The second was published 200 years ago this year and is still as exhilarating a ride as when the authorial ink was still wet on the paper.

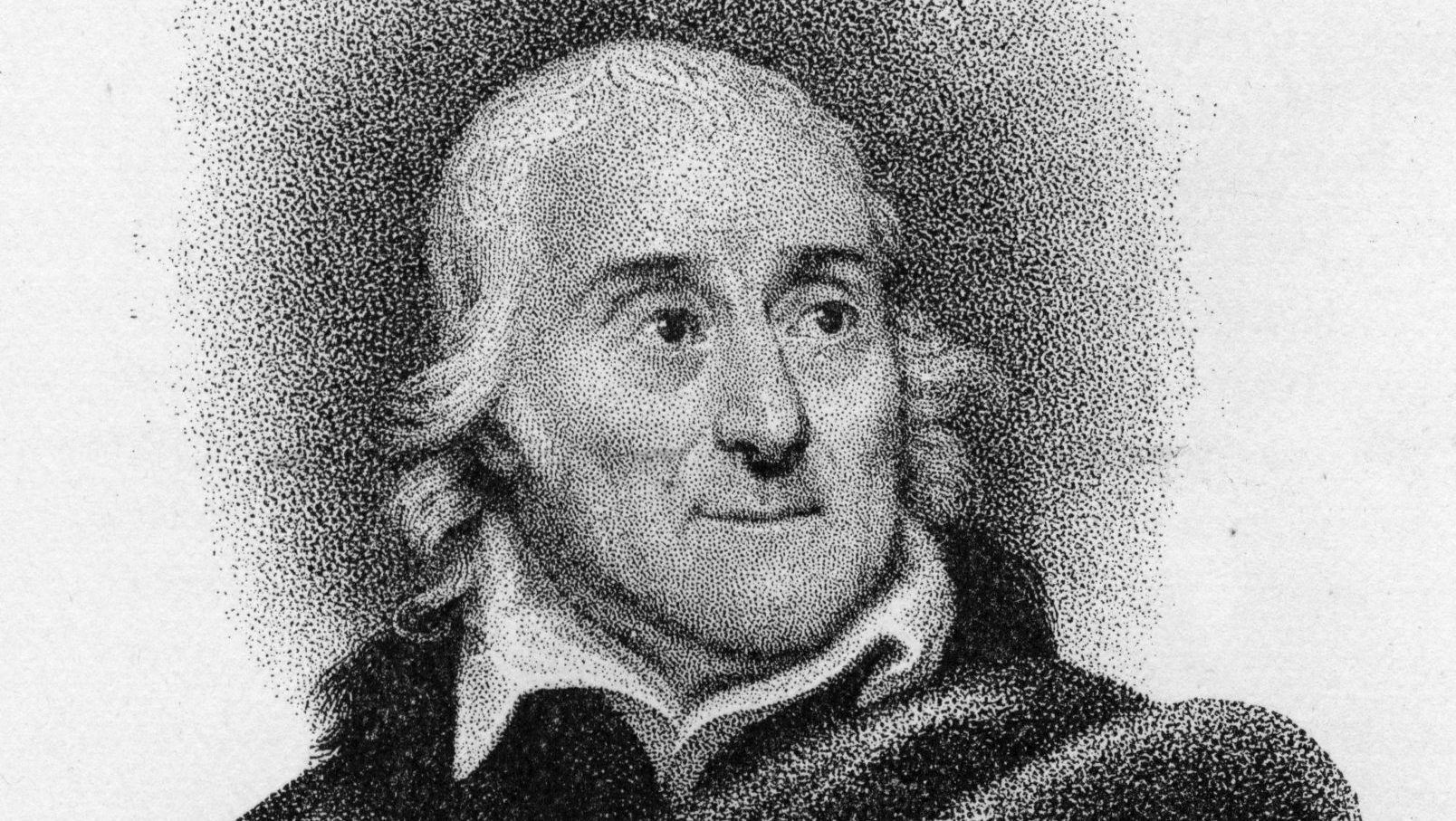

There is a decent chance you have never heard the name Lorenzo Da Ponte. Trust me when I tell you your Europhilia can only be enhanced by even a passing acquaintance with his story.

Da Ponte is best known as the librettist who collaborated with Mozart on three of the greatest operas ever written: Don Giovanni, Cosi fan tutte and Le nozze di Figaro. He was also a close friend of Casanova, had the ear of Habsburg emperors, led first an itinerant European existence that took in Venice, Vienna and London, then embarked on a second act in the United States that saw him occupy a variety of positions, from greengrocer to the first professor of Italian literature at Columbia University.

I was only introduced to Da Ponte’s Memoirs this year, the 200th anniversary of their publication, and am already wondering how I got this far through life without them. They are tremendous. Erudite, catty, hilarious, snooty, picaresque, this is a thunderously entertaining book written by a man who spent his life, according to his own account, as either the hero of the hour or the victim of some outrageous injustice cooked up by jealous adversaries.

Elisabeth Abbott’s English translation of Memoirs, published by New York Review Books, runs to almost 500 pages yet the pace never drops and the stories never stop coming. It’s like a cross between Don Quixote and The Pickwick Papers with a sprinkle of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy and a hefty dollop of Brucie-level conceit.

To give you some idea of the tone, take Da Ponte’s first mention of Mozart. While he deigns to acknowledge the great composer’s extraordinary talent, he points out immediately how “it was to my perseverance and firmness alone that Europe and the world in great part owe the exquisite compositions of that admirable genius”.

Even removing Da Ponte’s entertaining self-aggrandisement from the tale, his is still a remarkable story of determination, reinvention, autodidacticism, meritocracy, polymathy, scandal and adventure.

He was born Emanuele Conegliano in 1749 in Ceneda, a small town in the hills north of Venice, the Jewish son of a tanner. His mother died when he was five and when he was 14 his father sought to remarry, choosing as his bride a girl only two years older than his son. Not only that, she was a Christian, compelling the whole family to convert to Catholicism.

Young Emanuele grew up illiterate, and were it not for his forced conversion there is every chance he would have followed his father into the tannery business. Instead, as was traditional for newly created gentiles at the time, Emanuele Conegliano took on the name of the Bishop of Ceneda who baptised him and became Lorenzo Da Ponte. New name, new life, new opportunities. And what opportunities.

Thanks to the bishop he was educated at the local seminary where before long he was already noting his own immense potential.

“I was capable in half a day of composing [in Latin] a long oration and perhaps 50 not inelegant verses”, he wrote, as well as apparently learning the whole of Dante’s Inferno by heart within six months of learning to read modern Italian.

In 1773, at the age of 24, he became ordained as a priest, “wholly contrary to my temperament, my character, my principles, and my studies”, and moved to Venice where he soon became a devotee of “cards and love”.

After 10 cloistered years in the seminary, Da Ponte was soon thoroughly enjoying himself. He had a string of liaisons with Venetian society women, most of them married, until one entanglement in which he was sleeping with both a nobleman’s wife and mistress – as well as the dissemination of some poems he’d composed that were not exactly flattering about various Venetian dignitaries – saw him banned from the city for 15 years.

By 1781 he had arrived in Vienna, determined to become a librettist. He contrived an audience with Joseph II himself and talked his way into a job at the emperor’s newly formed opera company where he made the acquaintance of Mozart and created the works that sealed for Da Ponte a cultural reputation that endures today.

“Da Ponte had an understanding of the human condition far in advance of anything else at the time,” the mezzo-soprano Ann Murray said in 2012. “While Mozart is a genius, the extraordinary flair of Da Ponte has never been fully realised.”

Both men became favourites of the emperor, but when Joseph died and was succeeded by his son Leopold, Da Ponte found himself banished from Vienna too.

“Sacrificed to hatred, envy, the profit of scoundrels!” he railed, blaming his success – “these glories of mine” – for his downfall because enemies at court were jealous enough to conduct a whispering campaign against him.

This might be true up to a point, but it didn’t help that soon after Leopold acceded to the throne, Da Ponte had sought his patronage while also informing the monarch that “My destiny does not depend on you because all your power and that of all possible kings has no rights over my soul”.

From Vienna he washed up in Trieste where in 1789 he met and married Nancy Grahl, an Englishwoman 20 years his junior. They planned a move to Paris on the strength of a letter of introduction to Marie Antoinette that Da Ponte had been given by Joseph, but visiting Casanova in Bohemia on the way, the infamous rake persuaded him to forsake Paris for London, advising, “Once there, never visit the Cafe degl’Italiani, and never sign your name”.

Da Ponte took the first part of his friend’s advice, fortunately for him as otherwise he would have wandered straight into the middle of the French Revolution, but as for the second part, he put his name to some hare-brained business deals that brought a procession of creditors to his door.

In 1805, with what cash he had left in his pocket and a violin under his arm, he hid in Gravesend until he found a boat sailing for the US and set out for a new life, cursing “those men who made their way into my compassionate heart with the usual weapons of the hypocrite and the fawner and then ended their jest in the cry: ‘Death to him! Death to him!’ spitting in my face the blood they had sucked with cunning from my veins”.

He lost most of his money at cards during the voyage and found himself working as a greengrocer soon after his arrival. Still convinced of his own brilliance, rather than hankering over the cabbages for a return to the Europe he loved, Da Ponte set about turning himself into its manifestation in America for the cultural edification of the young country.

Despite some characteristically disastrous business ventures – disastrous purely because of the jealousy of those who sought to destroy him, of course – he made a success of a bookshop in New York, brought over an opera company for the first American staging of what he called “my opera, Don Giovanni” and at the age of 84, five years before his death in 1838, opened New York’s first purpose-built opera house.

His Memoirs, written over several years towards the end of his life, are unquestionably flawed. We learn next to nothing of the Venice and Vienna of the day, there is no personal insight about either Mozart or Casanova, who remain incidental throughout, nor do some of history’s most significant events, such as the French Revolution, warrant a mention. Even Napoleon is only namechecked once, and that was because Da Ponte’s father met him. Or at least thinks he did, the old tanner was not entirely sure.

There is instead plenty about Lorenzo Da Ponte – and that is just fine. His life makes a rattling good yarn taking in some of Europe’s great cultural centres at great cultural moments. Yes, it is viewed entirely through the prism of the author’s unshakable conviction of his own excellence but, to be fair, having produced three of the greatest libretti in the history of opera one has to concede he has a point.

Two hundred years after the publication of Memoirs, Lorenzo Da Ponte would still make a terrific evening’s company in a wine tavern. He would probably become curmudgeonly and bitter after a few rounds, but for the stories he had and his proficiency at telling them, I, for one, would happily put up with that. Pass me a goblet.

Memoirs by Lorenzo Da Ponte, trans. Elisabeth Abbott, is published by New York Review Books, price £8.99