When Paris welcomes the world for this summer’s Olympic Games, they will officially be the 33rd Olympiad. However, for some they will actually be the 34th Summer Olympics.

In 1906, ten years after the city held the first Olympics, Athens hosted a second Olympics; the only summer Games to take place outside the current four-year cycle. However, although recognised as official by the IOC at the time, it has subsequently disappeared from the history books.

As with so many subsequent Olympics, the 1906 Games became a political battleground. On one side were those who wanted the Olympics to be permanently based in Athens to preserve continuity with the Ancient Olympics and reinforce Greek nationalism. On the other was those, particularly Pierre de Coubertin, who wanted the Games to rotate venues to buttress their modernity and internationalisation.

De Coubertin’s idea for the revival of the Olympics was approved at a meeting of like-minded aristocrats at the Sorbonne in 1894. The Frenchman wanted the first of these new, modern games to be held in his native Paris in 1900. However, following an impassioned speech by Greek delegate Demetrios Vikelas, they were awarded to Athens in 1896.

The International Olympic Committee was formed and Vikelas became its first president and did much of the organising of the first Olympics, de Coubertin focusing instead on another event—his wedding. Much of the financial support for the 1896 Games came from a bequest from another Greek, the late philanthropist Evangelis Zappas.

At a reception for competitors, the Greek King Georgios I made an appeal for the city to be nominated as the “permanent and continuous arena of the Olympic Games”. The Greek Royal family had been established just over 30 years earlier and this endorsement tied them to the country’s people and Greek ideas of nationalism. The Greek cabinet drafted a law to this effect and the American team wrote an open letter to The New York Times supporting the proposal.

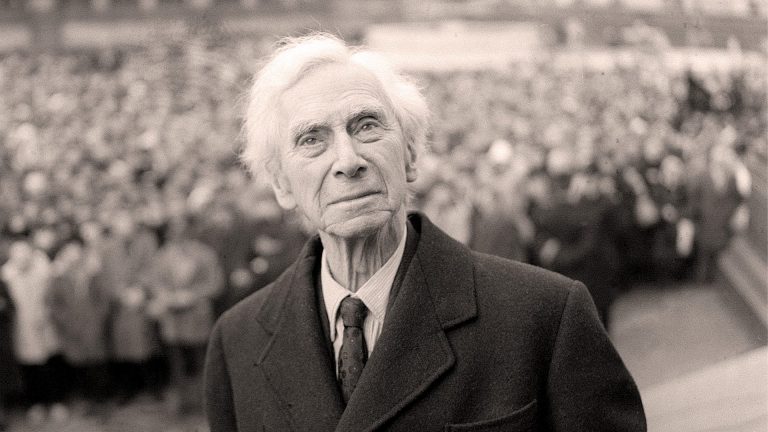

Now president of the IOC, De Coubertin unequivocally rejected the idea. He sought to disassociate his vision for the ‘modern’ Games with alternating host cities in Europe and North America (it would not be until 1956 that the Games would venture beyond these continents), from the ancient counterparts. However, the ‘Greek Plan’, as it was known, had not been killed off. It was revived in 1901 and despite De Coubertin’s opposition, won approval from the IOC.

This was in part because the Games held in Paris the previous year had been a disastrous, poorly organised affair. Stretched over months, it is not clear how many countries sent competitors and only retrospectively did the IOC decide which events would gain official recognition.

The IOC was marginalised from the Games’ organisation, and they were overshadowed by the World’s Fair held in the same city at the same time. The term ‘Olympic’ was little used with the athletic events instead called the ‘Concours internationaux d’exercices physiques et de sport’ (International physical exercises and sports), the Press variously labelling them ‘International Championships’ or ‘Paris Championships’.

Things were little better in 1904. The Games were again overshadowed by the World’s Fair and travel to St Louis, in America’s Midwest, was so expensive that just 62 of the 644 competitors came from outside North America. Nearly half the events were contested by the USA alone. It’s little surprise they topped the medal table with a total 231. Germany came second with 15.

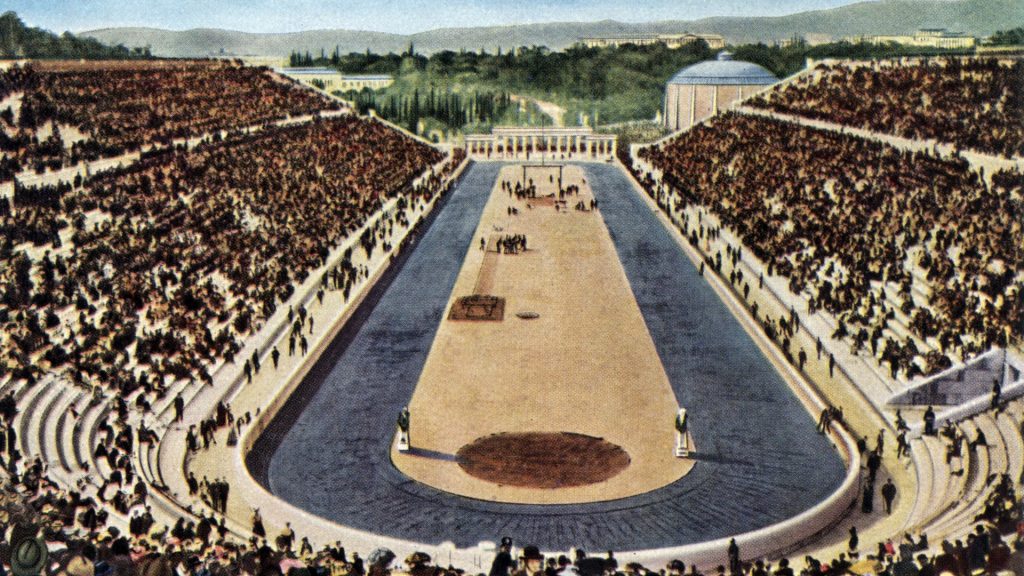

Thus, in 1906 the future of the Olympics was by no means certain. The second Athens Games provided just the fillip they required to restore confidence. In comparison to their two predecessors, they were widely recognised as being highly organised and genuinely international. Unencumbered by any link to a trade fair, events took place over a compact 11-day period. They were concentrated around a major stadium within a major city which became consumed by the Games for their duration.

They also introduced many of the Olympic traditions we recognise today. Athletes had to register through their National Olympic Committees (NOCs). Not only did this mean that people couldn’t just pitch up and try their hand at whatever event was taking place on the day, it also began the process of greater regulation for the Games in particular and sport in general. It also fostered a genuine spirit of international competition.

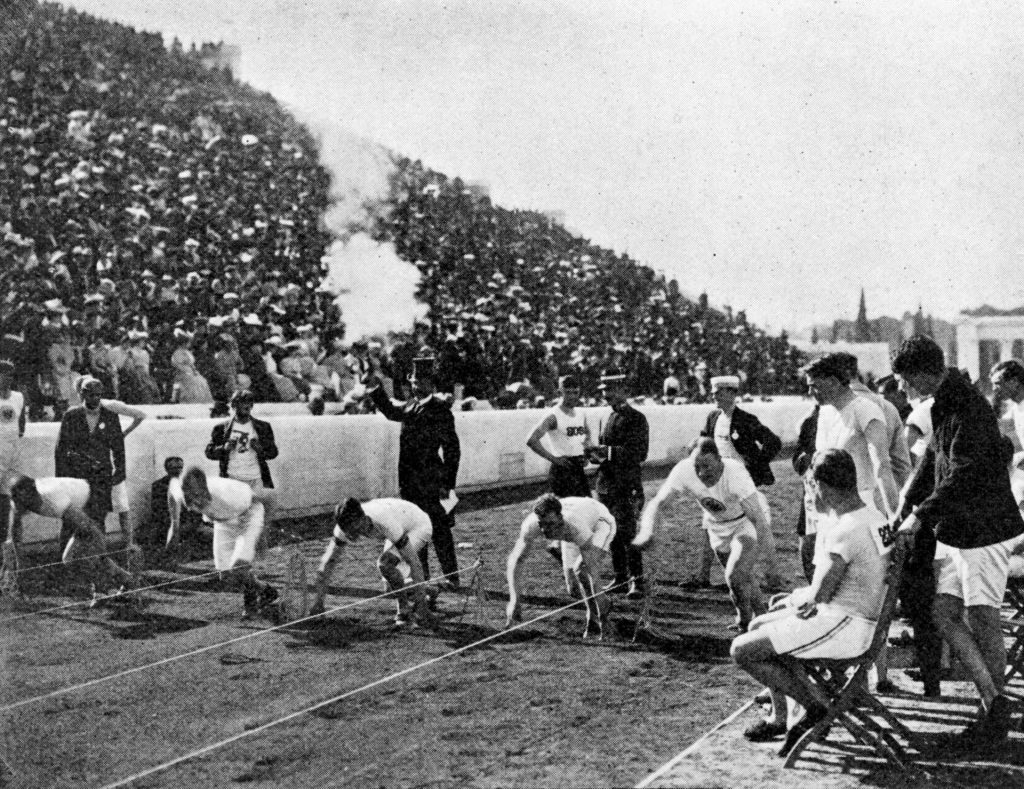

There were 74 events across 13 sports, ranging from athletics, swimming and football to tug of war. Twenty countries entered a total of 826 athletes, just six of whom were women, all competing in the tennis tournament.

“These were really the first international Olympics with a lot of people from a lot of different countries participating,” says Bill Mallon, the co-founder of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH).

The Games were the first to have an opening ceremony distinct from any event. Athletes, in national uniforms, entered the Panathenaic Stadium country by country, each delegation behind their national flag. Some 60,000 spectators were in attendance. Among them the Greek King Georgios I, his wife Queen Olga and his sister the British Queen Alexandra along with her husband King Edward VII.

The Games were also the first to have a closing ceremony, involving 6,000 local school children, and the first to fly the national flag of medal winners at the medal ceremonies. They were also the first to have a podium protest when Irish track-and-field athlete Peter O’Connor, angry at having been forced to represent Great Britain, climbed up a flagpole, where he unfurled a large flag adorned with a golden harp on a green background and the words “Éirinn go Brách” (Ireland Forever).

There is little doubt that at the time these were widely recognised as official Olympic Games. They had been sanctioned by the IOC, which referred to them as the ‘Second International Olympic Games in Athens’, although as in 1900 and 1904, they were not directly organised by the IOC. They received widespread coverage from the newspapers, which again recognised them as official games. “All the papers in Britain, Europe, the USA called them Olympic Games,” says Mallon.

They were also widely recognised as the most successful Olympics to date. “A lot of people say they saved the Olympic movement after 1900 and 1904 were such farces,” says Mallon.

James Sullivan, a contemporary American sports journalist, and member of the IOC, wrote in his book about the 1906 Games, that they “will go down in athletic history as the most remarkable festival of its kind ever held.” It was hoped, he wrote, “that future Olympic Games will be up to the standard”.

The British had sent one of the larger contingents of athletes and came fourth in the medal table, with 24, including eight golds. The success of the games helped encourage the British Olympic Association, with Royal approval, to step in and take over responsibility for hosting the 1908 Games, in London, after the Italians, who had initially been awarded the Games to be held in Rome, withdrew.

Games were scheduled to take place in Athens in 1910, with the Greeks and other NOCs making significant plans. However, simmering political tensions in the country meant they were cancelled. Preparations were again undertaken for Games to be held in Athens in 1914 (with balloon and aeroplane events to be included), but the assassination of Georgios I in 1913 and The First World War quashed those hopes.

There were no attempts to revive the Athens Games in the inter-war years, which made it easier for De Coubertin, who would remain president of the IOC until 1925, to ultimately have them all but erased from the Olympic history books. They were downgraded and rebranded as the “Intercalated” or “Intermediate Games”. None of the medals won or records set in 1906 count in official Olympic records.

In 1948, a motion to formally recognise the Athens Games was put to the IOC. However, a three-man sub-committee headed by Avery Bundage, who became IOC president three years later, rejected it with scant consideration. “The committee basically rubber-stamped the previous decision and that’s been accepted as the IOC’s policy ever since,” says Mallon.

Yet, although the IOC steadfastly refuses to acknowledge the 1906 Games, their vital importance to the Olympic movement’s longevity is still recognised by many. “Everybody in the International Society of Olympic Historians feels that those are Olympic Games, and very important Olympic Games,” says Mallon. In 2002, the ISOH, of which Mallon was president at the time, forwarded a motion to the IOC to recognise the 1906 Games supported by a 40-page document based on significant contemporaneous, primary-source research. It was rejected without explanation.

“We did a policy statement and a white paper for the IOC saying that these games should be recognised. It was very detailed, and they basically just brushed it aside. They didn’t even consider it,” says Mallon. To date, there have been no further attempts to overturn the IOC’s decision. “If they didn’t accept that, they’re not even going to listen to us.”