The history of cookery is populated by many larger-than-life characters, but one major absentee who deserves to be right up there alongside Auguste Escoffier and Mrs Beeton is Alexis Soyer. Celebrity chefs of today owe a huge debt to this transformative French Victorian chef, food author and philanthropist. The likes of Heston Blumenthal or Ferran Adrià might never have scaled the culinary heights they did without Soyer’s innovative approach and experimental kitchen.

“He’s one of my absolute heroes, one of the good guys and deserves to be far better known,” says TV food historian Dr Annie Gray.

Alexis Benoǐt Soyer was born in France but lived most of his life and achieved huge fame in England before dying at the age of just 48. The legacy

he created was immense. He revolutionised feeding the troops during the Crimean war and many military campaigns since have followed his guidelines. He sold cookbooks to raise funds to help those caught up in the Irish potato famine long before Bob Geldof was asking us for money. He travelled to Ireland to set up soup kitchens. His inventions ranged from portable stoves, timers and vegetable steamers to revolutionary kitchen design ideas.

According to Katie Rawson and Elliott Shore, authors of Dining Out: A Global History of Restaurants: “Soyer had long been both an inventive chef and a tinkerer. His self-proclaimed ‘culinary laboratory’ is not unlike that of El Bulli’s innovative and renowned chef Ferran Adrià.”

Soyer gave us our beloved fish and chips, publishing a recipe for them in his book Shilling Cookery for the People. He came across chips in Belgium and would often buy cod with a coating from Jewish street traders who would put the hot fish in newspaper to keep it warm for their customers. One day he decided to put them together and the rest is history.

Born in Meaux-en-Brie on 4 February 1810, at the age of nine Soyer joined his brother Philippe in Paris, where he was already an established chef. By the age of 17, Soyer had cemented his reputation, with 12 junior chefs working under him.

In 1829 he became assistant to the head chef of the Prince de Polignac. In July that year, they were creating a grand banquet when an angry mob burst into the kitchen and shot two of the chef’s brigade. Soyer saved himself by bursting into a spirited rendition of the Marseillaise. The mob loved him

and carried him on their shoulders out into the street (at least that’s how Soyer told the story afterwards).

With the tumultuous political situation in France, he fled to London in 1831. He quickly established a reputation of note and was eventually appointed as head chef to private members’ institution The Reform Club. His appointment coincided with a major refurbishment of the building, which allowed him to work with the architect to create a state-of-the-art cooking space, with his main contribution being the “sophisticated control of temperature”. It had a large oven flanked by boiling stoves, soufflé ovens, a steam closet and water-cooled refrigerators. Most significantly, it used gas stoves for a cleaner and less dangerous working environment. Previously, burning large amounts of coal in enclosed spaces led to a build-up of lethal levels of carbon monoxide, which did not end well for the cooks.

Soyer was a flamboyant but charming self–promoter and was easily recognisable as he strode around London doing deals and planning new ventures. He was a household name at the time and was as well known for his inventive cooking as he was for his eccentric dress. Enveloped in a weirdly shaped cloak, he wore a trademark red hat and carried a slanted cane.

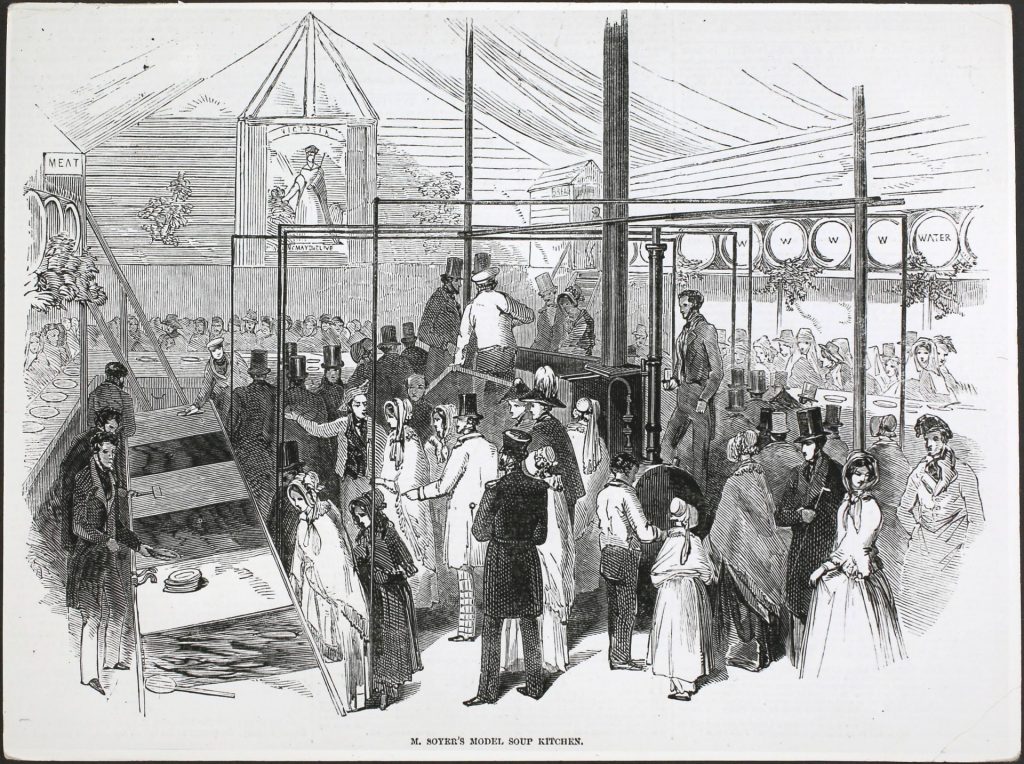

While at the Reform Club he heard about the plight of the Irish population

during the potato famine of 1847. The club granted him leave of absence and he went to Dublin to set up the first dedicated soup kitchen, where he served the famine soup he had created specially. At its peak it served 5,000 people daily and his efforts were fundamental in saving many lives. Soyer’s soup kitchens became a model for charities such as the Salvation Army and Oxfam.

“He received no rewards from his adoptive country for all his humanitarian deeds – he’s simply the man history forgot,” his biographer, Frank Clement-Lorford, says. “Yet during his time he was considered the greatest chef in the world.”

After 13 years at The Reform Club, Soyer resigned. He leased Gore House, where the Royal Albert Hall now stands, and in 1851 opened Soyer’s Universal Symposium of all Nations Restaurant. He tried to capture the excitement of The Great Exhibition of that year. Each room was decked out in an extravagant theme such as the Grotte Des Neiges Eternelles and La

Chambre Ardante d’Apollo. In the grounds he had a large marquee called

the baronial banqueting hall. He hoped to entertain and feed 5,000 people daily with different-priced menus. After three months it closed down with a debt of £7,000 – worth just over £1m in today’s money.

“It was the most flamboyant, fashionable restaurant ever seen in London,” noted Clement-Lorford.

Soyer loved being in the limelight and was in his element preparing outrageously elaborate dishes for his aristocratic patrons. His Chapons à la

Nelson featured chickens cooked in pastry shaped like the prow of a ship floating on a sea of mashed potato.

His belief in the importance of food provenance foreshadows the chefs of

the 21st century who inherited his celebrity mantle. In his book The Gastronomic Regenerator, he revealed where he obtained his ingredients.

Listing the farmers and fishermen who have grown or caught the food on offer remains a staple of higher-end menus today.

In 1855, after reading eyewitness reports in the press about the appalling conditions facing British soldiers on the battlefield and in hospitals in the Crimean war, the chef felt compelled to act. He offered to travel to the war zone at his own expense to ensure that the troops received nutritious food.

The Crimean war began in 1853 and within months it became bogged down

with casualties on both sides mounting rapidly. Along with incompetent commanders, disastrous military decisions and appalling medical care, feeding the troops became a major issue. The British army’s food supply authorities were notoriously inept and corrupt. British and French army caterers also bid against each other for local produce, pushing prices sky-high.

The majority of soldiers perished not from war wounds but from illness

often caused by grossly substandard food. Working closely with Florence

Nightingale and Mary Seacole, the celebrity chef from London had a profound influence not just on how food was prepared and served in the war but on the feeding of soldiers in future conflicts, too.

Soyer discovered that the soldiers on the front line were left to fend for

themselves. He decided that each regiment should have a trained cook, armed with a book of simple recipes written by the chef. He got the small

team he brought to Crimea with him to start teaching selected soldiers how to cook. The army loved this idea and created the regimental cook and the

Army Catering Corps. Their HQ is called Soyer’s House and every new trainee is taught about the history behind it.

To solve the issues with food preparation on the battlefield, he designed a field stove to replace the outdated tin kettles soldiers used to cook meals. Known as Soyer’s Magic Stove, it would revolutionise the way food was prepared for British soldiers. The stove resembled a rubbish bin perched on a burner. On top of this there was room for a large cauldron, which could hold enough to feed at least 50 people – eight times the volume of the tin kettles.

For over a century Soyer’s stoves were used by armed forces in Britain, Canada and Australia. They provided hot meals and tea in British cities bombed during the second world war and even went to the Falklands in 1982.

The Morning Chronicle in London observed: “He saved as many lives through his kitchens as Florence Nightingale did through her wards.” When the chef died, the great Nightingale herself was moved to comment: “Soyer’s death is a great disaster… he has no successor.”

The anglophile chef was an early promoter of “nose to tail” eating to minimise waste, an ethos still being championed today. The stigma that

offal and cheap cuts of meat are of poor quality has been around since at

least the Victorian era. Soyer despaired that so much good food was going to waste; he couldn’t understand why we turned our noses up at it while countries like France happily ate the whole animal.

It is also Soyer we can blame for the vast array of celebrity chef cookware

tie-ins. One of his inventions was the Pagodatique serving dish he used in

his restaurant. In his cookery books he tells readers that they can buy the dish from him or the manufacturer.

If this has whetted your appetite to try some of this remarkable man’s

recipes, his signature “lamb cutlets reform” are still on the menu at the

Reform Club just as they have been since 1846. Bon appetit!

Emma Luck is a writer specialising in food