On paper, British politics looks very different at the end of 2024 from how it did at the beginning. Entering the year, Rishi Sunak was prime minister and the Conservatives still had around 350 MPs. The majority was down from the 80-seat lead Boris Johnson won in 2019, but as the Tories entered their 15th year in power, it was still sizeable.

Labour overturned that in a landslide victory. Labour’s majority is north of 170, and Kemi Badenoch is leading a party with just 121 seats in the Commons. That’s a political revolution – and yet fundamentally, things still feel almost eerily similar.

Economic growth is still anaemic, and government money is still too tight to mention: departments have been asked to find 5% “efficiency savings” across the board. The prime minister has dragged hacks out of London to announce a government relaunch, even as his PR team insists it’s not a relaunch. Everything is supposedly different, and yet it all feels the same.

Labour will argue that it needs time – the country is in a malaise that will take years rather than months to clear, and the government should be judged by its first term, not its first few hundred days. Whether or not voters have the patience for that remains an open question – though telling voters when they should start caring is a risky proposition for any government. While it’s been a frustrating year of politics changing and yet staying the same, there have still been lessons from the year. Here are a few:

1.) Reform UK is now Britain’s main opposition party

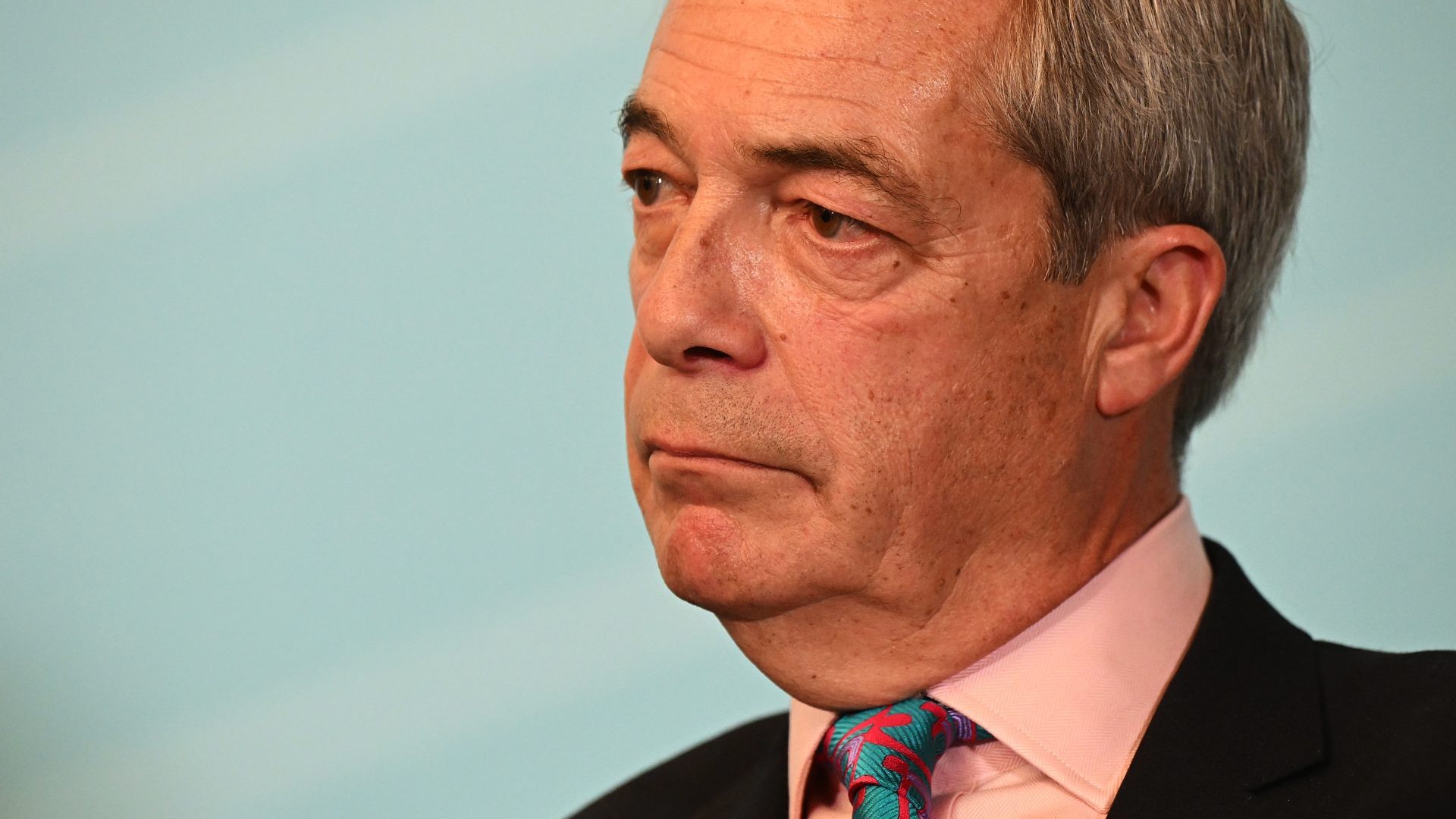

Kemi Badenoch is already demonstrating that she is leader of the opposition in name only. Both her own actions and the way the government is responding on immigration shows that both Labour and the Conservatives are more concerned about Nigel Farage and Reform than one another.

A particularly dismal December Prime Ministers’ Questions exchange between the two leaders highlighted this, and how catastrophic both parties’ response so far to the threat of Farage has been. Badenoch used almost all of her questions to lambast Starmer on immigration, to which he responded by chastising the Tories as the “party of open borders”, who had allowed net migration to soar in the years following Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal.

If Starmer and Badenoch were to record a party political broadcast for Nigel Farage, they could hardly have done it any better than that. Trying to be Farage-lite will not work for either leader: studies across the world have shown that when parties of the centre or centre right try this approach, it fails.

Labour needs to talk about issues other than immigration, while quietly fixing the backlog and similar issues. Talking about immigration will only boost Farage – they will never be able to do his schtick better than he can, and nor should they even be trying.

But the real significance is that both of the major parties are more worried about Reform UK – which is now polling about the same as Ukip at its peak – than one another. Reform only has five seats, and got 2.7 million fewer voters than the Tories in 2024, but its outsize influence on politics will continue for the next term. With Labour’s majority as commanding as it is, parliamentary maths is unimportant: to point out the Lib Dems have 10 times as many seats as Reform is to miss the point.

To acknowledge a fact is not the same as to welcome it, and the simple fact is that Farage is making the political weather now, and will continue to do so for the next several years at least.

2.) Labour’s ability to become a circular firing squad is alive and well

In the run-up to the general election, the Labour Party was a pressure cooker. Resentments and frustrations had been simmering for years, but the general election – and the determination not to do anything that might put a win at risk – kept a heavy lid on everything.

Shadow ministerial teams were frustrated that they were frozen out of decision making and had no influence on plans or policy. Starmer’s office was divided between a pro-Sue Gray faction, a Morgan McSweeney and Pat McFadden faction, and a third group of staffers exhausted by the constant drama between the two. MPs complained of being completely adrift, knowing no more than the media about the state of the party’s plans for government.

This dysfunction has made it across to government, and then some. Sue Gray is no more, having been effectively ousted by a combination of internal politics and a broader perception that preparing for the first days of government had been her responsibility and the job had been done badly.

But Labour’s backbiting didn’t stop with Gray’s departure – even if, for now at least, No 10 is calmer and more harmonious. There is much muttering over the rapid ousting of Louise Haigh over a spent conviction that Keir Starmer had been told about years before. This was not helped by No 10’s refusal to give details of the “new information” that cost Haigh her job.

Just last week, health secretary Wes Streeting openly attacked his cabinet colleague Ed Miliband over Syria – an issue a long way from either man’s current briefs. Six months in, the government is displaying the kind of backbiting, resentment and lack of discipline more typical of a party that’s been in power for decades. Labour needs to learn how to live with itself, or it will fall apart from within.

3.) Party loyalty is dead. The central question for voters now: What’s in it for me?

Perhaps, though, the lack of cabinet loyalty is one of the areas in which Labour is most in touch with the mood of the voters. The sentiment these days is very much that if you want loyalty, get a dog. Voters want results, and if they don’t get them they will look to another party.

The scale of Labour’s win came from winning back voters who had opted for Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party in 2019 – the distribution of those voters meant that Labour narrowly won lots of seats. When Labour tacked to the left instead, taking voters from the Greens and the Lib Dems, it merely stacked up tens of thousands of votes in already safe seats.

Labour purposely shed those voters, and they have quickly moved away to other parties. Similarly, voters who like the sound of what Farage says have shifted to new parties on multiple occasions and are happy to do so again for Reform. The era of lifetime party loyalty is long gone for many Brits – a concept that activists are finding even harder to grasp than politicians.

4.) The UK’s party mix isn’t compatible with its electoral system (and can’t be polled)

The UK general election votes of 2024 resembled that of a European country with a proportional system, even if the electoral system translated that into a very British landslide win for one party. Labour and the Conservatives collectively attracted less than 60% of the votes – they now barely poll 50% between them – but picked up more than 80% of the seats.

If these trends continue, it is a recipe for disaster. Voters get frustrated when the government can’t make the changes they want, but they also get frustrated when their actions at the ballot box don’t reflect the makeup of parliament.

The problem for ardent electoral reformers for most of the last few decades has been that because the UK was mostly a two-party system, the distribution of seats wasn’t too far removed from the distribution of votes. With the kind of five-plus party mix the UK has at present, that is no longer true.

Additionally, polling just cannot handle trying to translate that mix into seats under our system. First past the post is creaking at the seams and showing its age. Its time may soon be over.

5.) US-style disinformation laundering is here, and the parties need to get used to it

Despite the protests of many in politics and the mainstream media, disinformation was never an “internet problem”. The likes of Alex Jones and other fringe far right online figures became so dangerous in the USA because there was an industry to launder at least some of their views into the mainstream.

The conspiracy theory of “pizzagate” suggested that Democrats trafficked children under the guise of ordering pizzas. It began on 4chan, the conspiracy platform, and was “reported” by Jones. It then became included in Fox News segments that just “asked questions” about the “story”, before becoming a talking point in Congress – among Republicans, of course.

This laundering operation let the most effective and most insane anti-Democrat conspiracy theories enter the mainstream. Fox and the Republicans would come out with the sanest possible version of the story (by and large), leaving people to look up more online and find the real fringe insanity.

The UK has been a relatively tame information environment by comparison, because what started online tended to stay there. The rise of Reform and of GB News has changed the game.

The laundering operation has arrived and its effects are already all too apparent: Farage and GB News have proven themselves willing to play some very nasty and dangerous games over the Southport killings and subsequent riots, and false rumours about Keir Starmer’s involvement, or the family of the attacker.

This is largely new in 2024, but it won’t stop here: it will likely only escalate. Labour in particular, but mainstream politicians as a whole, will have to be alert to the threat and respond far better than their US counterparts – unless the UK wants to wake up to its own version of Donald Trump in the not-too-distant future. Now there’s a thought for the bleak midwinter.