“‘More than 50 years have passed since then,’ declares the calendar, that old bookkeeper in the office of history, who controls chronology and with ink and ruler marks the leap years in blue and draws a red line at the beginning of each century,” wrote Erich Kästner in his 1957 memoir published in English as When I Was a Little Boy. “‘No!’ cries memory, shaking her curly locks. ‘It was only yesterday. Or at most the day before.’”

This week marks the passing of 50 years since the death of Kästner in Munich at the age of 75. The author of one of Europe’s greatest children’s books, Emil and the Detectives, and one of its most underrated adult novels, Fabian, Kästner was a man who lived through and chronicled extraordinary times.

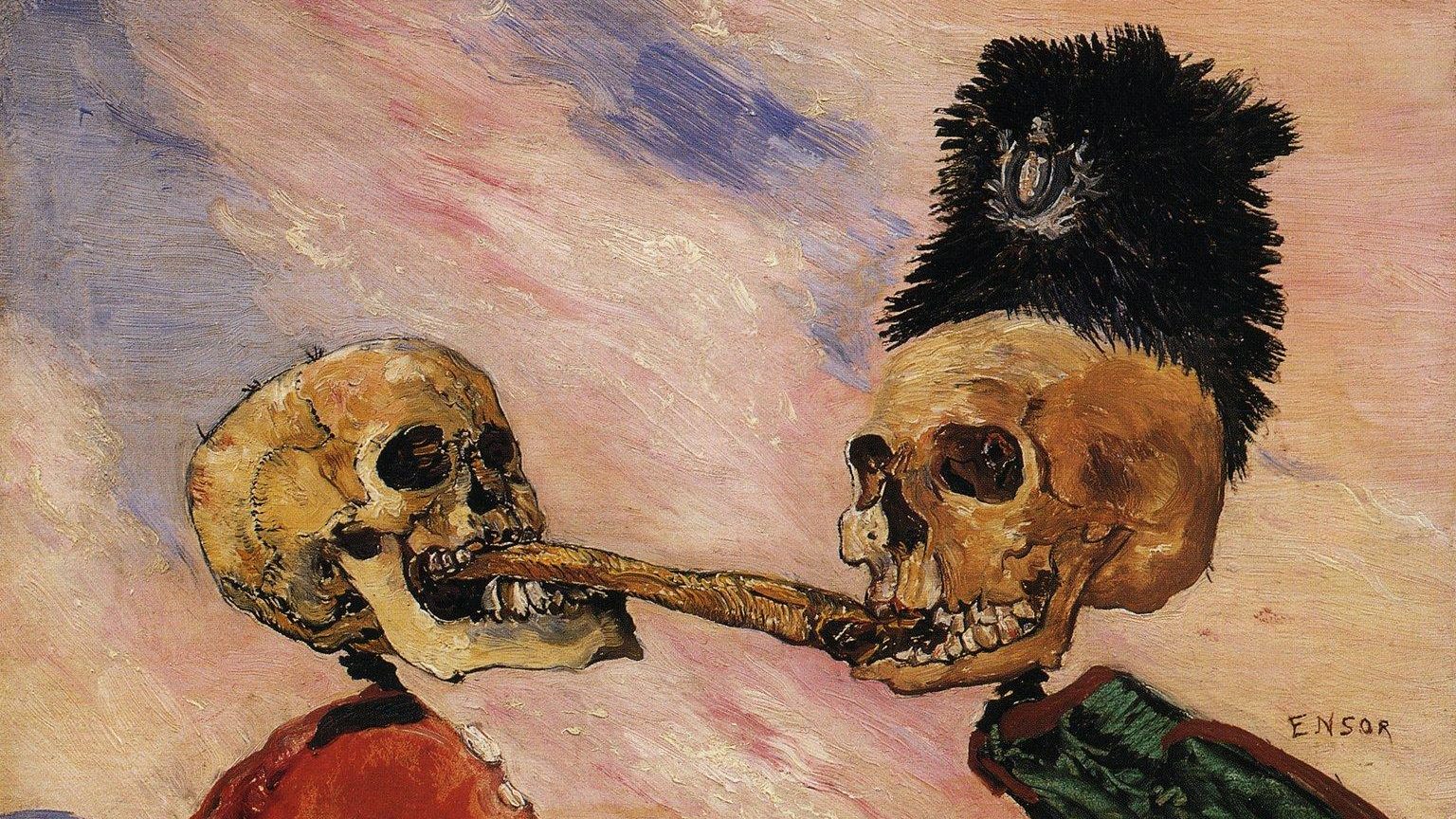

The night of May 10, 1933 was a drizzly one in Berlin, but around 40,000 Berliners still made for the city’s Bebelplatz where the Nazi student association, Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund, had organised their highest-profile stunt yet. It was a Säuberung, the “cleansing” by fire of works by writers whose work, politics or ethnic background offended the new arbiters of morality.

A pile was made of 25,000 books, petrol was poured over them, then flaming torches set them ablaze.

Joseph Goebbels was master of ceremonies, cajoling the crowd into a frenzy with a speech broadcast live on national radio that announced “the era of extreme Jewish intellectualism is now at an end”, before naming names in a series of what were called “fire oaths”.

“No to decadence and moral corruption!” he roared. “Yes to decency and morality in family and state! I consign to the flames the writings of Heinrich Mann, Ernst Glaeser and Erich Kästner.”

The flames licked around the hill of books, sending a thickening column of smoke into the night sky, fanned by the breeze and exhorted by a frenzied crowd. Among the burning volumes was almost all of Kästner’s published work, but especially his 1931 novel charting the last days of Weimar decadence, Fabian: Die Geschichte eines Moralisten (Fabian: The Story of a Moralist), condemned by the party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter as a “filthy tale” littered with “descriptions of subhuman orgies”.

Also among the conflagration were works by Karl Marx, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Erich Maria Remarque, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Bertolt Brecht, Ernest Hemingway, Anna Seghers, Franz Kafka, F Scott Fitzgerald, Rosa Luxemburg, Radclyffe Hall, Stefan Zweig and DH Lawrence, but only one of the persecuted authors was there in person to see their work burn.

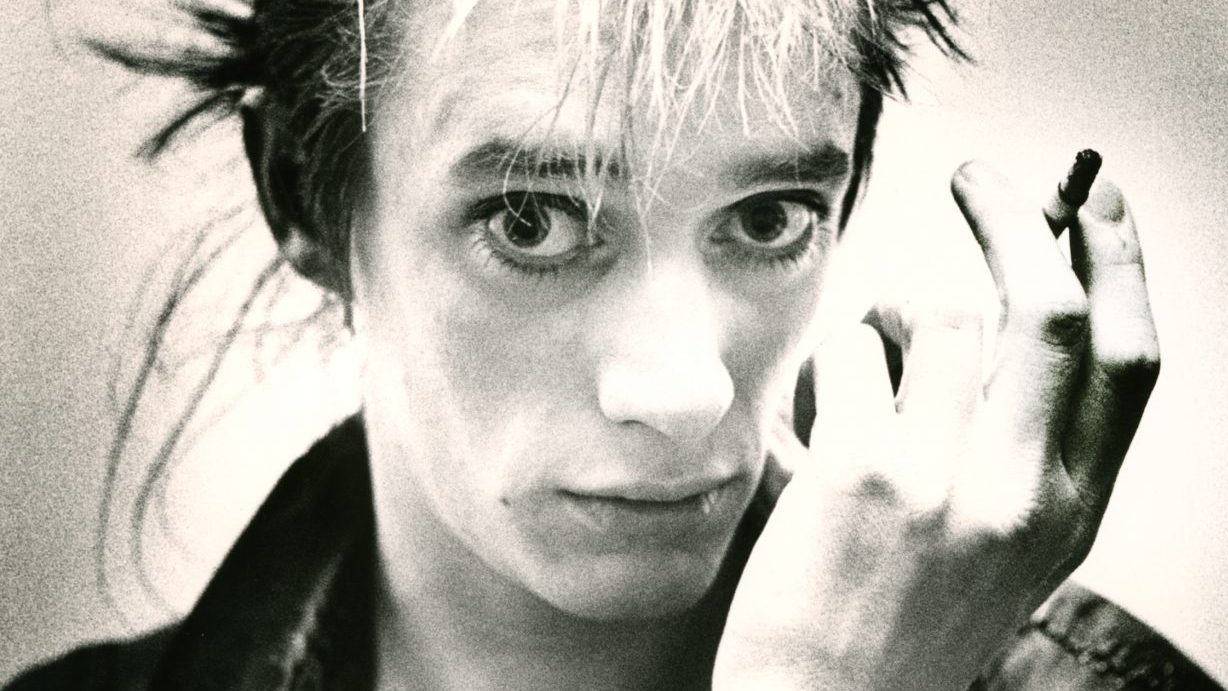

Kästner watched nervously, the orange glow from the flames illuminating his pale face among the ranks of damp hats and coats steaming in the heat from the blaze. He was there, he reminded himself, to observe, gathering material for a future novel.

If the atmosphere had been ugly to begin with, as the flames soared up into the night it became hideous. A woman nearby glanced round at him, frowned slightly as if she knew him from somewhere, then her eyes widened.

“Erich Kästner!” Her voice rose above the deep roar from the fire, hand rising to point in his direction. “Erich Kästner!”

He pulled down the brim of his hat, turned around and hurried from the scene, brittle black flakes of burnt pages drifting down on him out of the night like a malevolent snowfall.

The same scene was playing out across Germany, with Kästner’s books among those being burned in Munich, Greifswald, Göttingen, Heidelberg, Marburg, Kiel, Hanover and even his beloved home city of Dresden.

Most of the living German authors whose books turned to ash on the Berlin cobbles that night were either in prison or had already fled the country, but while Kästner knew he was in danger, he felt compelled to stay. These extraordinary events required the eye of a gifted chronicler such as himself, he thought. Also, there was no way he could leave his mother.

Three months earlier, he had been visiting the Austrian Tyrol when he learned of the Reichstag fire and the mayhem subsequently unleashed. He hurried back to Berlin, writing to his mother that “staying out of the country is out of the question. I have a good conscience and if I left I would always blame myself for being a coward.”

He had sensed that something was coming. Fabian had captured brilliantly the end of Berlin’s decade of decadence, the collapse of the Weimar Republic, the economic disaster that went with it and the fear that worse was yet to come.

“The near future had made up its mind to mince me into sausage meat,” he had written. “I was in a great waiting-room and its name was Europe. The train was due to leave in a week. I knew that. But no one could tell me where I was going or what would become of me.”

The madness of Nazism had to be temporary, he thought. If he could stick it out until natural order was restored, there were rich literary pickings to be had in the national self-examination that would surely follow. Never lacking in self-regard, Kästner saw himself as a key figure in charting this horrific blip in the national story, just as he had chronicled the end of Berlin’s wild years.

It took until after the war for him to admit he would never write the era-defining work he had planned.

“The German Thousand-Year Reich was not material for a great novel,” he wrote in 1945. “The task of architecturally untangling the limbs of the millions of victims and hangmen that had piled up over 12 years was impossible. You cannot set statistics to music.”

His faith in the ultimate goodness and wisdom of humanity had diminished the longer fascism retained its grip. By the time the war ended and the shattered country began to find its literary voice again, it was too late for Kästner.

While sales of Emil and the Detectives in particular, first published in 1928, afforded a comfortable lifestyle for the rest of his life, he found himself eclipsed by new waves of writers with plenty to say about the present rather than the past.

Born in Dresden in 1899 to a master saddle-maker and a hairdresser, Kästner was called up to the German army towards the end of the first world war and, while never sent to the front, the experience confirmed in him a lifelong antipathy to militarism.

On being demobbed he enrolled at the University of Leipzig and obtained a master’s degree with a thesis on Frederick the Great, funding his studies by writing for the Neue Leipziger Zeitung. The 1927 publication of his risqué poem Abendlied des Kammervirtuosen (Evening Song of the Chamber Virtuoso) led to his dismissal from the newspaper and prompted a move to Berlin, where he commenced the most productive and successful period of his life.

Emil und die Detektive appeared a year after Kästner’s arrival in Berlin and was an immediate sensation. The story of a boy who is robbed of a sum of money while travelling on a train to Berlin, and his subsequent quest to apprehend the thief with the help of a gang of local kids, was a groundbreaking work of children’s literature, unusual in that it was set in contemporary Germany rather than a fairyland of medieval castles, and featured parents as significant characters.

The book, which paved the way for a wealth of European detective fiction for children, sold more than 2m copies in Germany alone. It was widely translated, and adapted for the cinema in 1931 with a screenplay by Billy Wilder and Emeric Pressburger. Emil und die Detektive was so popular it was even exempted from the Nazi book ban.

Kästner would undoubtedly have been on the Gestapo radar anyway, but it was Fabian that sealed his place among the writers condemned by the regime. Its explicit – for the times – descriptions of sex, prostitution, drug use, infidelity and rapacious hedonism was practically a checklist of everything the Nazis despised, even in the heavily sanitised version produced by a nervous publisher (the unexpurgated original would not appear until 2013).

Yet, perhaps feeling that the success of Emil und die Detektive afforded him some degree of leeway with officialdom, Kästner attempted to continue his writing career. He even applied – unsuccessfully – for admission to the Nazi writers’ association Reichsverband Deutscher Schriftsteller, membership of which was compulsory for any living writer hoping to be published.

He had three novels produced in Switzerland and worked on screenplays for Berlin’s Ufa film studio under a pseudonym, but it took the destruction of his apartment in Charlottenburg during an air raid in 1944 before he began to think seriously about leaving.

When it became clear the following year that not only were the Russians heading for Berlin but also that the SS planned to execute him, Kästner fled to the safer surrounds of the southern Tyrol on the pretence of a non-existent filming project.

When he returned to his home city of Dresden after the war and saw how it had been all but destroyed by allied bombs, his grief was profound. “I was born in the most beautiful city in the world,” he wrote. “In a thousand years was her beauty built, in one night was it utterly destroyed.” Kästner’s pacificism was only strengthened by what he saw in Dresden and, having relocated to Munich, he was optimistic in the immediate postwar years that the ultimate lesson of the Third Reich would be the obvious disaster of militarism.

When Germany began to re-arm and join Nato as part of its postwar “economic miracle” in the 1950s, he realised he was outside majority thinking and became increasingly disillusioned.

He marched against nuclear armament and the Vietnam war, and was elected president of the West German branch of the international campaigning writers’ organisation PEN, but disenchantment exacerbated a descent into alcoholism, and he died from cancer 50 years ago this week on July 29, 1974.

In 1953, 20 years after watching books including his own burning in a Berlin square, Kästner had written: “In the modern, undemocratic country the hero becomes an anachronism. The hero without microphones and without the echo of a newspaper becomes a tragic buffoon… He becomes a martyr. The official cause of his death is pneumonia. He becomes a nameless obituary.”