The philosopher Umberto Eco grew up under Italian fascism – so when in 1995 he wrote his seminal essay “Ur-Fascism”, he knew what he was talking about. Indeed, Eco recalled winning prizes as a child for giving speeches in favour of the glory of dying for Mussolini.

Eco thought deeply about the essence of fascism, and its persistence as an idea. Nazism, he argues, is its own distinct political form – unique in its imagery, core ideology, and more. Fascism, though, is a much wider phenomenon, and an administration or party can tend towards fascism without containing any of the core traits of Nazism.

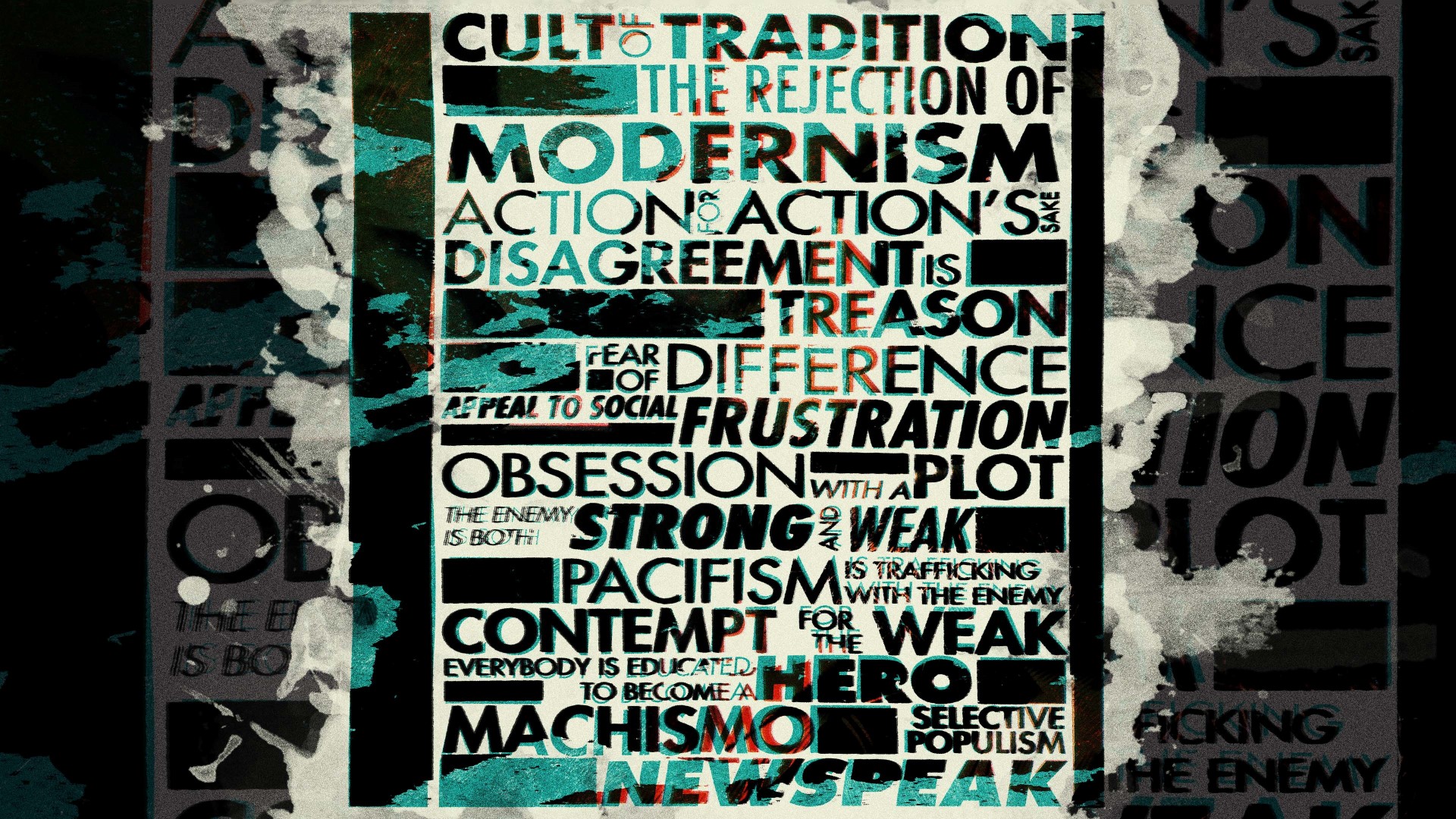

This, he argued, was part of what made fascism so dangerous: even those who had experienced fascism could have it creep up on them again in the future, only spotting its re-emergence once it was too late. Eco set out 14 different characteristics of fascism, arguing that any of them on their own could prove enough for a government with fascist characteristics to coalesce about.

These included rejection of modernism, a cult of tradition, a fear of the other, and a fixation on the idea of plots or conspiracies against the mainstream. It would be nice if this essay – approaching its fourth decade – was an object only of academic interest and curiosity; it is anything but.

Right across Europe – and beyond it – there are political leaders and political movements that, if they are not currently outright fascist, are at least exhibiting some of Eco’s 14 traits about which an overtly fascist regime may rise. What follows is an account of some of the continent’s political leaders and the prescient warnings of Eco from almost 30 years ago.

The Netherlands’ Geert Wilders is one of the European politicians most easily categorised as traditionally far right, as his Party For Freedom is best known for its relentless anti-Muslim rhetoric – as classic a case of relying on fear of the other as is possible. Wilders has called Islam “totalitarian” and referred to Moroccans as “scum”.

Wilders had softened his traditional anti-Islamic rhetoric during the election campaign in which his party shockingly took the most seats, but that doesn’t stop the extremity of his policies – which include banning the Qur’an and headscarves, and closing mosques.

Wilders might be at the helm of the largest party in the Netherlands, but it is still very much in doubt as to whether he will form the next government in the country. The same cannot be said in Argentina, where anti-establishment iconoclast Javier Milei has won the presidency.

Milei’s ostensible politics are distinct from fascism: he is more like a radical libertarian, in that he wants to entirely scrap multiple government departments, switch Argentina’s economy to use the US dollar (curtailing the ability of its central bank to act), and abolish action against climate change.

But Milei has the populist’s need for enemies: he has called the pope the devil’s representative on earth and a spreader of communism – a divisive move in a country with a sizeable Catholic population – and he has served as something of an apologist for the dictatorship of the country in the 1970s.

Milei’s grand plans are likely to stall once they make contact with reality, but other populist leaders seem to be navigating the pressures of government more skilfully. Italy’s Giorgia Meloni is trying to cement power by changing the electoral system of her country to make it easier to directly elect prime ministers.

Core to her electoral appeal is – in line with one of Eco’s 14 fascistic traits – a call to tradition, idealising the traditional family unit (although Meloni is now a single parent herself) and offering financial incentives for families to have more children.

Meloni is charming and skilful at making her opinions seem mainstream – despite acting to curb asylum, challenge LGBT rights, and other such hard-right stances. Like a twisted Mary Poppins, Meloni is excellent at providing a spoonful of sugar to make her medicine all the more palatable.

The same cannot be said of Donald Trump, who is now a virtual certainty to be the Republican candidate for the US presidency, leading the field by more than 40 points after the disintegration of Florida governor Ron DeSantis’s campaign. Trump might feel like a known quantity, given that he was president once already, but this would be to underestimate the danger he poses.

Since the January 6 Capitol Hill riots, Trump possesses, if anything, too many of Eco’s warning traits: his administration relies on machismo, on enemies within and without, on the othering of immigrants and ethnic minorities, on appeals to an imagined golden age of America, endless obsession with plots, and even the use of simple and repetitive rhetoric.

Trump is facing more than 100 criminal charges, none of which would prevent him taking the presidency again – but which would probably provoke him to act even further outside the bounds of normal behaviour.

Despite the fact that a second Trump administration could prove a threat to the very fabric of American democracy, he is if anything the favourite to win the 2024 election, thanks to Joe Biden’s poor polling. More troubling still, the Democrats swapping candidates would do nothing to help – every other likely candidate does worse than Biden in a match-up. Barring some major surprises, America might be headed in a dark direction.

Should Trump win re-election, he would find no shortage of strongmen-style leaders to stand alongside. When it comes to Vladimir Putin, there is no need to reference Umberto Eco or any other philosopher to know he’s an autocrat, but other administrations friendly towards him are somewhat more complicated.

Within the EU, there is Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, a long-standing Eurosceptic – and Hungarian nationalist and traditionalist – who is increasingly emboldened to act. Orbán is mounting a national campaign against continued EU membership, but is also acting to all but ban civil society groups, having already more or less chased George Soros’s organisations from the country (plots: check, othering: check).

As his tenure grows longer, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is similarly taking on the strongman role, leveraging his unusual position as a Nato member with a friendly relationship with Russia – amid increasing concerns that Turkey is supplying Russia with arms, some of which may be US-produced.

They are joined by a new friendly face in the form of Slovakia’s Robert Fico and his new government, which has pledged to send “not a single bullet” in the cause of Ukraine’s war. The populist uses a playbook that should now sound familiar – having alleged that his opponents (possibly aided by the EU) would rig the vote or try to stage a coup against him. Othered groups for Fico include, as is all too common, LGBT people, Muslims and asylum seekers.

Meanwhile in Sweden, Jimmie Akesson of the Sweden Democrats made a speech last weekend in which he proposed a ban on the construction of new mosques and suggested that existing ones might be destroyed too. A few years ago in what was once judged Europe’s ultimate liberal democracy, this would have been written off as the ravings of a crank. But Akesson’s party is the largest in Sweden’s right wing governing coalition, which exists only because he gives it confidence and supply.

This list isn’t even exhaustive – but it does speak to one thing: it became received wisdom a few years ago that a populist wave in Europe was a myth, the dog that didn’t bark. That now looks complacent: the all-clear was given far too soon.

Across Europe and beyond there are refreshed and renewed populist governments, many of them displaying multiple indicators of fascist potential. Those listed are just those in government or who have won their election – this is not a list of parties on the fringes that might one day become a threat, it is a list of those in power (or close to it) today.

There are plenty of reasons to worry that list will grow. Emmanuel Macron has barely held Marine Le Pen’s rebranded National Rally at bay, and she is likely to be a serious contender for the presidency next time it is contested – especially after a summer of discontent across the country this year. In Germany the far-right AfD party– with co-leaders Tino Chrupalla and Alice Weidel – has managed to break out of its traditional eastern European heartlands in state elections, coming second in the Hesse region around Frankfurt and third in Bavaria.

In Spain, Santiago Abascal’s Vox are emboldened by socialist PM Pedro Sánchez’s deal with Catalan separatists, which with Trumpian rhetoric Abascal has called a “coup d’état”. Greece has not one, not two, but three different far right parties in its parliament, including Spartans, which is backed by Ilias Kasidiaris, who has been allowed to become a YouTube sensation despite the fact that he is currently serving a 13-year sentence for membership of the violent neo-Nazi Golden Dawn group. Nowhere seems immune.

We should also not hesitate to consider our own situation, either. The Brexit argument was predominantly won on a play to tradition (“take back control”), with Leave.EU appealing against an “other” in the form of immigrants. Rishi Sunak is facing multiple populist challenges from within his own party, especially from Suella Braverman. The UK’s perennially unpopular populist Nigel Farage is enjoying primetime exposure on ITV.

The Conservative Party as any kind of vehicle for responsible governance or moderation is unlikely to survive long past Sunak’s leadership – what emerges in its place could make even the current vindictive mess look mainstream. Sunak allows his government to pull populist stunts over immigration, trans rights, conspiracy theories like 15-minute cities, and more. What follows could be worse.

Umberto Eco grew up with fascism all around him. It is no longer mere scaremongering to wonder whether today’s infants might do the same.