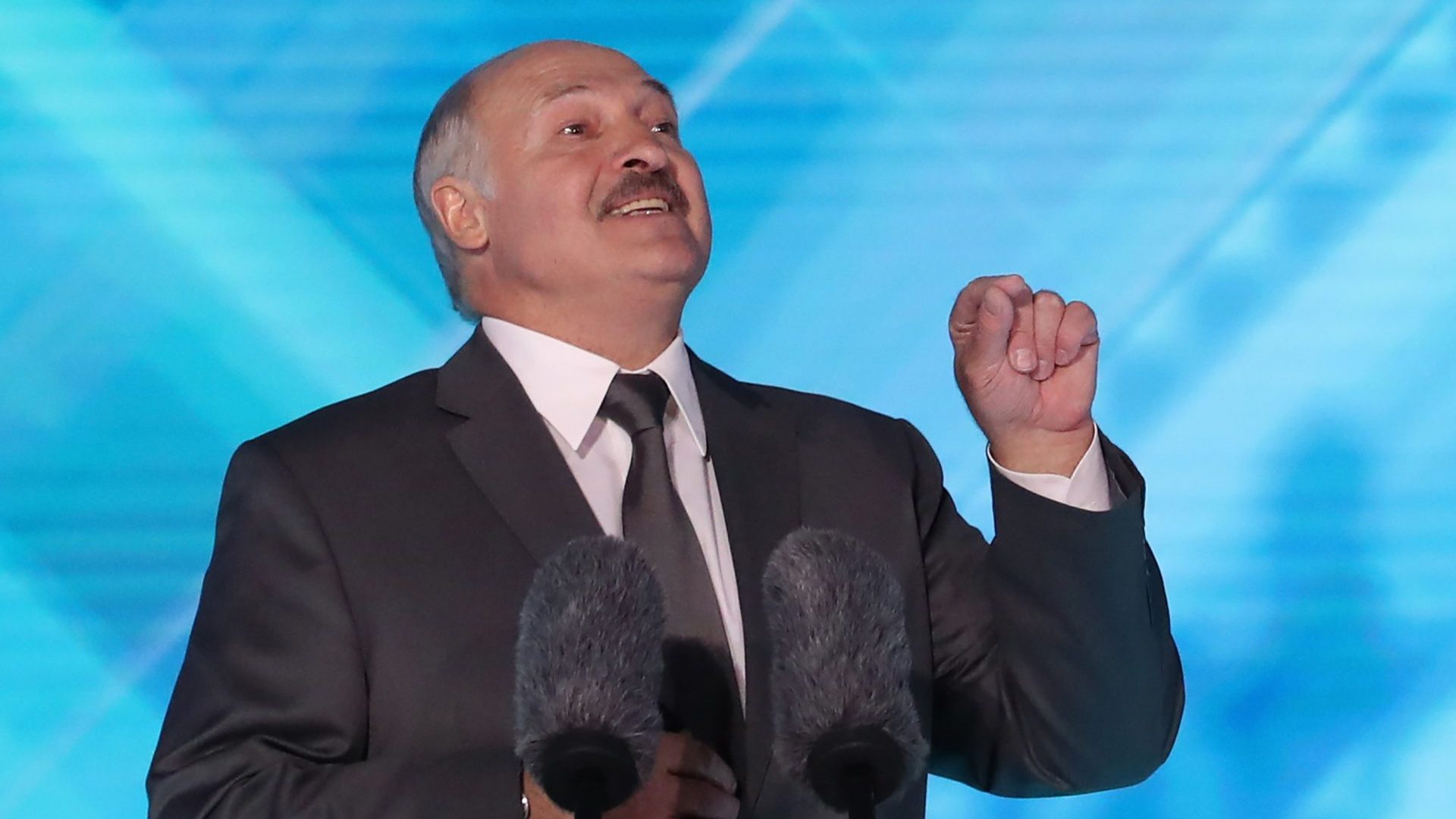

The question at the heart of this election was never who would win, but by how much the incumbent president of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenka, would steal the vote. The answer came on Sunday. He won 86.8% of the vote: a new record for the president’s 30-year rule.

Lukashenka barely campaigned at all, telling factory workers he was simply too busy. In reality, vote rigging made the result a foregone conclusion. Lukashenka’s closest rival, Sergei Syrankov of the Communist party, took 3.2% of the vote. “We understand who’ll be the winner in this race,” Syrankov told Russian state media. “We fully support that.”

Activists were threatened by security services in the run up to the election. Those are not idle threats – 1,265 political prisoners already behind bars. No invitation was sent to Europe’s main election observation body, the OSCE, and voters were banned from photographing their ballot papers – a tactic previously used by opposition activists to check whether votes were being fairly counted.

“These are not elections but a ‘special operation’ to illegally cling to power,” said Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the leader of the Belarusian opposition. She remains in exile after standing against Lukashenka in the country’s 2020 elections. Her husband, Sergei, was jailed in Belarus for 18 years after organising anti-government protests. “We will never accept [Lukashenka].”

Lukashenka’s stage-managed victory was intended to show a government firmly in control. During the last elections, five years ago, thousands of pro-democracy protesters flooded the streets in defiance of the regime. Although they were violently dispersed by police, the memory of that protest lingers.

But while Minsk tries to project an image of stability, the reality of different. State oppression is only intensifying, says Olga Dryndova, a political scientist at the University of Bremen and editor of Belarus-Analysen.

“Belarus is still not North Korea, but there are signs of a state trying to control all the spheres of society, including the private sphere,” she says. “Elections now play a different role: it’s not about trying to show a façade of democracy, it’s about showing control over society, control over the elections, and control over the political system.”

As well as the pseudo-democratic sheen of the vote itself, Minsk released more than 250 political prisoners in the run-up to the election, a signal of willingness for fresh dialogue with the West.

“Lukashenka wants to try and win back some legitimacy: for [the West] to call him the president and talk directly to him. As a rule, a lot of countries don’t do that now because they don’t recognise him as president,” says Dr. Andrew Wilson, a historian at University College London.

Such recognition is not only a matter of pride for Lukashenka himself: it would give Minsk a greater chance of shedding some of the sanctions currently imposed against it, for reasons ranging from Belarus’ role in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to political persecutions.

In a joint statement, the EU diplomat Kaja Kallas and EU enlargement commissioner Marta Kos described the vote as a “sham election” that was “neither free, nor fair.” The US State Department also denounced the vote. “Repression is born of weakness, not strength. The unprecedented measures to stifle any opposition make it clear that the Lukashenka regime fears its own people,” it said.

But Lukashenka’s leadership is less tied now with the ballot box than it is with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Minsk has battled to ensure it does not become directly embroiled in the conflict, although it has allowed Russian troops to launch attacks from its territory.

“Lukashenka has managed to be a co-aggressor against Ukraine, but has avoided sending troops to fight there. Belarusians like that,” says Tatsiana Kulakevich, an associate professor at the University of South Florida.

“For the last 30 years, the ideology of the Belarusian state has been ‘Belarusians are a peaceful people’. It’s so ingrained, this idea that we don’t want to be ‘like Ukraine’.”

An unfavourable turn to the war for Putin will mean more pressure for Minsk to commit its own armed forces to the cause – or even the potential loss of Minsk’s most important ally. Such scenarios are likely to leave Minsk increasingly hopeful for peace talks – particularly if Belarus can escape international ire in any final deal.

“If they forget about Belarus during peace talks between Russia and Ukraine, then Belarus is screwed because nothing will change,” says Kulakevich. “People in Ukraine are paying for freedom with their lives. In Belarus, they are dying too – except hidden in jail.”